Interview: ‘Burden of Dreams’ editor Maureen Gosling on Herzog’s ‘Fitzcarraldo’

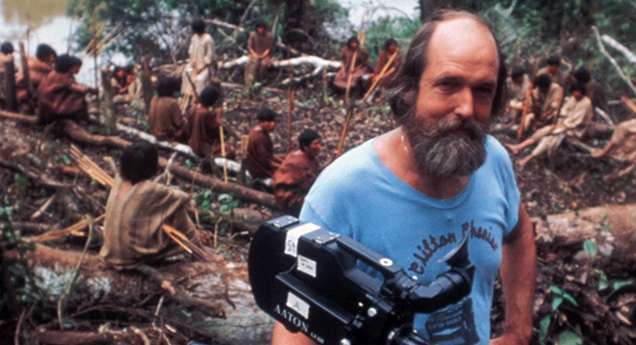

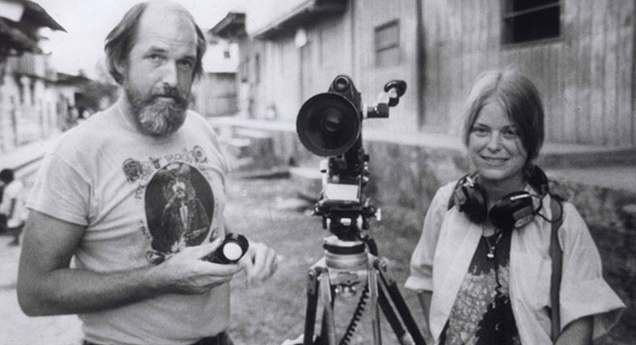

Playing as part of this year’s NZ International Film Festival sampler Autumn Events, Burden of Dreams chronicles the making of a film detailing possibly insane obsession, directed by the possibly insane Werner Herzog. As Herzog shot Fitzcarraldo in South America, cameras rolled on him as a subject too, resulting in fascinating doco Burden of Dreams. Editor Maureen Gosling joined us on the phone to share her experiences documenting this piece of cinema lore.

FLICKS: How does it feel to keep having conversations about a project that was made so long ago?

MAUREEN GOSLING: Well, it’s actually fun. It’s nice to be able to talk about it in retrospect, rather than going through it, I guess you’d say. And I do appreciate the fact that it still is timely and it still resonates with people and it holds up over time. It’s an adventure film and Herzog’s such a really interesting character that it really does hold up.

What do you think it is about the film itself, that continues to have new audiences finding and relating to it after so much time?

I guess it’s because there is a lot of drama in the situation. And also, a lot of the issues are certainly issues that could still be discussed now, in terms of even the ethics of film-making and so forth, and indigenous people being involved in films. And how far should a film-maker go to realize his or her dreams? Just the humour in it, I think, is timeless, as well as the complexity of the situation. The multi-cultural stuff that goes on, the inter-cultural exchanges and conflicts and so forth. I think that it’s almost mythical, and the real situation was mythical and has mythical proportions, so I think it can transcend the times.

Do you think it’s very possible for film-makers to find themselves in that position today? Or are aspects of Herzog’s film unique to a specific time?

Yes, it is quite specific to the times in some ways, I think a lot of indigenous people have more awareness about outsiders and so forth. So, some things are connected to the times that it was made, as well as some that are relevant now.

I suppose in some ways it’s never been easier to take a camera anywhere. But it also might be not the easiest time either to convince people that it’s a good idea to pay for you to do that.

Well, people are also making their own films. So, there are a lot of indigenous people I know that are in South America who are making their own films. For example, I don’t know if the [inaudible], or the [inaudible], or [inaudible] have been able to make their own films. And I don’t know how much exposure they even have now to some of the technology. But it’s pretty amazing how many films like the film festivals that you can find, people telling their own stories which I think is really great. And the whole digital realm definitely allows for that. And it’s just easier with the equipment and it’s better quality and lighter, and all that good stuff. We definitely had a lot of technical issues at the time with our camera and recorder. We had to deal with humidity. We had to deal with just having enough electricity to charge our batteries. And so, we were constantly having to pay attention that or we’d lose our technology.

I imagine that you would have really appreciated modern edit suites when you went to put ‘Burden of Dreams’ together!

Yes. I think so. The film has been restored a couple of times and now it’s a really great condition. Thanks to Criterion and Harold Blank, [director] Les Blank’s son. The one thing that I would love to redo or work on again is the soundtrack because it’s a mono track, made for 16 millimeter, and now we could have stereo for the music, and so for then– so it would be fun to be able to do that. And also just a lot of things are easier. You still have to have a sense of storytelling and a sense of creativity and so forth to do a film with whatever technology you were using. And I find that if I do go back to a 16-millimeter editing table, I can actually do it still, even though it’s cumbersome feeling now. I feel like things are so much faster and I can almost do things as fast as I think, these days, in editing.

When you sat down with the footage from the film, how monumental a task was it to start assembling it into a narrative? Or did you have something in mind when you began the editing process?

Well, it was pretty daunting, of course, because we did shoot a lot for the times. These days people shoot 100 or 200 hours and think nothing of it and that’s because it’s cheap and because people just shoot and shoot and shoot and they don’t really think about that fact that every single shot could be used in 16-millimeter. Which was much more expensive, and so you didn’t have quite as much footage to work with, but we realised that we needed to tell the story of Fitzcarraldo because if people didn’t see the Fitzcarraldo, they wouldn’t necessarily understand what was going on. And we did decide that we wanted the film to stand on its own instead of just being an auxiliary element to Fitzcarraldo. And we also wanted to show how the experiences were affecting Herzog, so that we did have a character arc that we were dealing with, and we didn’t know how much of the first part to put in there. It had to get balanced against the second part when Klaus Kinski joins in because the first part could’ve been a lot longer because there was plenty of other dramatic footage we could’ve put in. But, we realised that we needed to get to the point of the actual production that was happening.

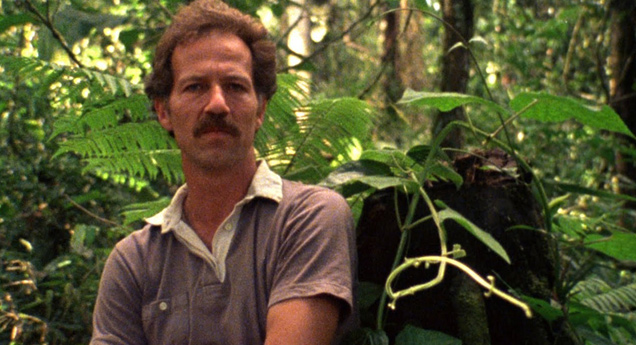

He’s obviously a crazily unique human being, Werner Herzog, but as you made your film, did you find yourself relating to any of the experiences that he was having with ‘Fitzcarraldo’ at the same time?

We were certainly part of it all. We were going through the same kinds of things that the crew was going through and we were dealing with the rain and just the logistics of getting places and the mood in the camp after being there for lengths of time. And people getting bored and that’s part of it that shows in the film. And yeah, it did allow us to get to know the people a little better and Herzog was less “crazy” than I had envisioned him to be before, because I’d heard stories of him jumping into cacti and jumping into rivers with piranhas and so forth. And I expected him to do that kind of thing but he really didn’t. His vision was crazy, and he stuck to his vision. And that was a little scary, especially when he was trying to make arrangements with the Brazilian engineer who told him that if he [wanted to do things a certain way], it could harm people and people might be injured. So, that was the part that was “crazy” in terms of him. On the set, he was very calm. He was very reasonable with people, and I only heard him actually raise his voice about three times during the whole time we were there. So, Kinksi made up for his calm [laughter] in actual manifest craziness.

I’m really curious about just being in the presence of Klaus Kinski, and what he was like when cameras weren’t rolling. What was that like to witness or even interact with?

Well, he was a consummate professional when it came to getting down to business. Although, he sometimes complained about things when they were shooting. And he did have some outbursts during some of the shooting. The one time that I remember the best was when he got angry with the shortwave radio that had this irritating sound that was constant. But they had to leave it on in case somebody was trying to get in touch because that was the only contact we had with the outside world. But it was driving him crazy, and he just stormed up these bamboo steps to the dining room which was also created out of the local materials. And he was so angry that he kicked in the wall of the dining room, and people got really nervous. And when that happened, they thought, “Oh my God. Kinski’s gone nuts.”

It must have felt the beginning of the end every time he got a bit loud, or anything slightly outrageous happened, right?

Yeah, you just really didn’t know what was going to happen and if Herzog was going to be able to calm him down, because he and Walter Saxer, the location producer, who was doing so much work, and he was working his butt off. He and Kinski sometimes got into it and it always had to be — Werner usually was the mediator.

Do you think it’s an advantage or disadvantage for documentary makers to be in the trenches with the subject, as you were with this one?

I think it’s a great way to do it because it was one time when we really had the time to spend. We were there a length of time, and sometimes for budgetary reasons or other restrictions, you can’t just hang out with your subjects. When I first started working with Les Blank, that was one thing that we were able to do. The first film I worked with him on in Louisiana, we stayed for two or three months and just were able to get to know the place and sink in. And when I did my film, Blossoms of Fire, in the ’90s, I was restricted financially so I could only be there in this town in southern Mexico for about a month. And so, I really had to prepare myself a lot more ahead of time to figure out what I wanted to do and would loved to have just stayed there and got to know people better and so forth. So, this film, we were able to be there a total of about three-and-a-half months. One month on the first location and two-and-a-half months on the second location. So, it did allow us to really get in there and it’s a luxury, I would say. There are some film-makers who are still able to do it, but it’s not as easy to do, unless you have a subject that’s local, which I actually do right now, which is nice.

What are you working on at the minute?

Well, it’s a brand-new film about this blues singer, jazz singer, folk singer, political activist named Barbara Dane. And she was known in the 50s, 60s, and 70s and has also had a record company and a blues club. And she’s just a very inspiring woman who is about to turn 90 and she’s full of amazing stories. And she still sings and she sold out two club engagements last year. And we went with her to Cuba. She was the first American to tour Cuba after the revolution. Anyways, so I’m literally just working on a sample tape for a grant today that I have to finish

Excellent. Well, look, fingers crossed that it all goes well. Good luck with the paperwork and the admin!

‘Burden of Dreams’ and ‘Fitzcarraldo’ play at NZIFF Autumn Events

Burden of Dreams

Auckland – May 10 and 19 | Wellington – May 3 and 10

Fitzcarraldo

Auckland – May 13 | Wellington – May 7 | Christchurch – May 7