Turning film frames into paintings – Flicks interviews the co-director of Loving Vincent

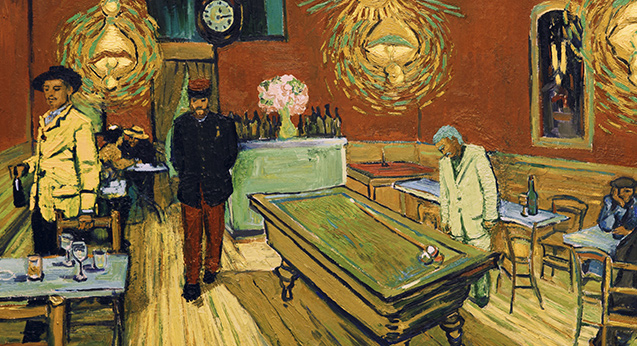

Nominated at this year’s Academy Awards and Golden Globes, Loving Vincent is an animated film unlike any other. Written and directed by Hugh Welchman and Dorota Kobiela, the story focuses on the mysterious death of painting legend Vincent Van Gogh.

The film uses a new oil painting for each shot, with movement added from one frame to the next by a painter’s brush. Around 100 artists have been involved in the film, and in the process have composed more than 56,000 paintings.

Loving Vincent comes to cinemas February 8 (find times & tickets). Liam Maguren got to chat to Welchman about this highly ambitious project.

FLICKS: Transferring still life to animation, is it like adapting a book to screen?

HUGH WELCHMAN: No.

We were, in a sense, adapting a book to screen and adapting pictures to screen. Very often, those two contradicted each other. We were working from [Van Gogh’s] letters and from the historical reality of his life. Also, we could only tell that through the paintings that he did.

It was a really tricky triangle to have the dramatic film script that we wanted, to have it told through the painting that we wanted, and perhaps that not contradict the historical reality.

Painting is a different art from film. Film is a story told over time, whereas for a painting it’s just one single moment and one very considered composition. Vincent used all sorts of frame sizes whereas for film you can only use one frame size. So that was a problem.

Vincent painted all year round, whereas our film was set one week in summer. We had to think about how we were going to deal with that problem.

Also, in 2D you don’t need to worry about things like skeletons and perspective in the same way that you do if an image is moving, so there were lots of false perspectives. There were characters made up of a few brush strokes that defied biology, so we had to try work out how to get around the rules of physics and biology when we were recreating it for the film.

Did you get any backlash from art purists or any art historians about this project?

A lot less than we were expecting. When I did Peter and the Wolf, people were like, “Peter and the Wolf should be left alone as it is as the narrator is on stage with an orchestra.” But really, we’ve had a lot of support from Vincent scholars and the Van Gogh Museum.

We’ve been working with them since 2013 and they’re absolutely thrilled by the film, we worked with the Kröller-Müller Museum which holds the second biggest collection of Van Gogh’s in the world, and we worked with the Musée d’Orsay in Paris with National Gallery. The top Van Gogh establishments around the world have been incredibly supportive, and we didn’t think that would happen.

We thought there would be some kind of reactionary voices, but I think they’re kind of glad that we’re highlighting the paintings through the film, whereas on the films that they’ve done, they’re live action and the paintings are sort of props in the background. Here, it’s actually the paintings telling the story, and it’s very difficult to conceive of Vincent’s story without the story of his paintings, without his paintings, which is why he was the perfect subject matter for this kind of film.

Is that what you would say prevents this film from being kitsch or gimmicky?

What prevents it from being kitsch is the fact that we did so much genuine research over so many years and working with the museums and going into a lot of research detail.

We found out which order Vincent put the paints on the canvas, whether he mixed them on the canvas or whether he pre-mixed them. The Van Gogh Museum has all of this information about the paintings in their collection.

We read all the letters. Between me and Dorota, we read over 30 books on Vincent, including all the most important biographies, and all the eyewitness accounts of people who met him.

It’s a big responsibility to be interpreting the work of someone so famous, and really the only solution we had was to try and be respectful by properly doing our research and thinking it through.

In going from one medium like painting to a medium like film, we’re reimagining his work. We’re not copying it because you can’t copy it. You have to approach it in a different way for film.

Roughly how long would it take to paint 10 seconds of this film?

Depends which 10 seconds.

On average, it took a third of a second per animator, per day. So it takes 30 man-days to do 10 seconds.

However, for example, the opening shot when we descend from the stars in Starry Night down to the town of Arles was the hardest shot in the film. It was taking two weeks to do one second, so the best part of half a year to do 10 seconds.

In the past, on films, we’ve done big elaborate shots and at the end of it I’m like, “I’m not sure it was worth it. We went too far.” But, with this one, we felt it was justified because it would allow people to really know that they’re entering a different kind of world.

Were there any cuts that you made after everything was painted?

Very little. We did do it, but it was incredibly painful because we’ve been sitting in the studio while someone was painting that shot for six months, or something like that.

We cut three shots after we painted them – the story’s always king.

What happens to the paintings now?

For each shot in the film, we have a canvas. The whole shot is done on one canvas, apart from the really long shots. There were 850 shots in the film, so we had around 1,000 paintings at the end of the process.

120 of them are in our main exhibition, which is in the Noordbrabants Museum in the Netherlands, and we have a couple of small exhibitions as well. So around 200 paintings in exhibition. I think 130 went to financiers and the cast.

Since we finished filming, we sold 100 through our website and most of them have sold. That means we’ve got another 500 to sell. There were places in the film where we fade to black or fade to white, and those paintings, I’m not sure we’ll ever get sold [laughter].

I’ve got 10 bucks lying around. I’ll buy one of those.

Yeah, no, I’d buy it for 10 bucks. They look pretty cool, because you’ve got the colours underneath. You never know.

Have you ever imagined what it would be like if Van Gogh ever saw this film?

He’d be very happy that 125 painters were paid, and hired, and worked together all because of him. One of his great dreams was to set up a studio with other artists, and unfortunately, that sort of failed at the first hurdle when his relationship with Gauguin disintegrated in the yellow house, and he had to go into the mental asylum after that experience.

I think he’d be very happy that a community of painters had been created because of him, and those painters have gone on to work together after the film, and they’re exhibiting together, and all sorts of things. I think he would have been just flabbergasted and also embarrassed that his work is so famous.

His first question would be, “Well, what about these other painters? Why am I so much more famous than them? They’re really amazing painters too.” And then, I think, beneath those sort of protestations of humbleness, he would’ve been very happy that he’d achieved what he wanted: he really wanted to touch people and communicate with people.

That was a big sadness in his life that he wasn’t very good at doing that in the flesh and he really wanted to touch people with his work. So I think he would be overwhelmed with happiness that the mission that he’d set himself just succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams.

‘Loving Vincent’ is in cinemas Feb 8th – click for movie times