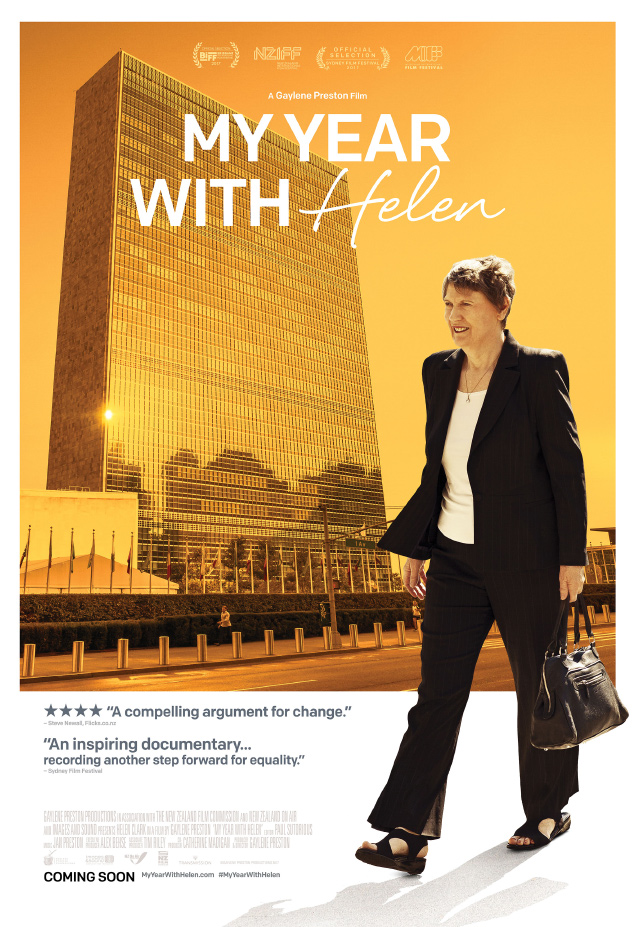

An In-Depth Conversation with Gaylene Preston About ‘My Year With Helen’

Following former NZ Prime Minister Helen Clark in her quest to become Secretary-General of the United Nations, Gaylene Preston’s documentary My Year with Helen offers a unique insight into an oblique process, and revealing access to its subject. As we noted in our four-star review, the film makes “a compelling argument for change at the head of the U.N. and other male-dominated political institutions”.

With My Year with Helen about to play the NZ International Film Festival, after its world premiere in Sydney last month, we jumped at the chance for an in-depth conversation with Preston about her film.

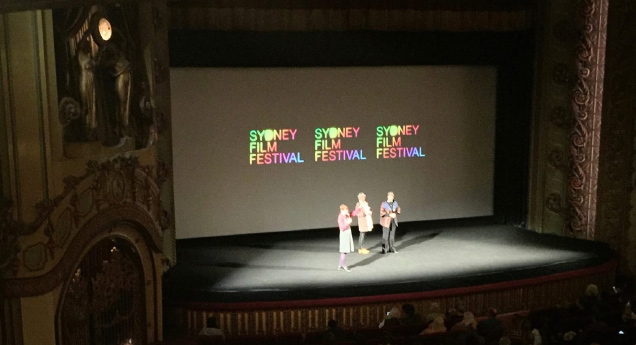

FLICKS: I saw the film in Sydney at the State, at the world premiere, which was a great way to kick it off.

GAYLENE PRESTON: I don’t think it gets much better than that. That was my fifth film there at the State. First actual premiere there, and I’ve always found that that’s a great space. It’s a great cinema to show your film and so is [Wellington’s] Embassy. The State is like the Embassy times two, really, isn’t it? It’s got a similar vibe, and the Civic is always amazing because the Civic’s a bit more sort of stately, do you know what I mean?

There’s something about a big theatre – like State and the Embassy – where it’s got a real gathering place feel in it.

I don’t know what it looked like from the stage as you came out to greet the audience after the film, but it seems like when you’re in the audience there that there’s great sightlines onto the stage. So I suppose you’re eyeballing people once you’re up there, right?

I’ll tell you what, that is breathtaking. The first time I walked on to that stage at the State cinema… It’s the same with the Civic, actually. I go up there with the lions and you feel like a little ant [laughter]. The space is so big, and when it’s full of people, it’s just got this vibe to it that’s electric. It’s brilliant. And that’s before the film’s screened.

But at the State, that was a memorable moment. There are standing ovations where some people are sitting, clapping, while some people are standing and putting their coats on and it kind of gradually becomes a bit of a standing ovation. But when a huge audience like that just leaps to its feet as one and does a spontaneous thing like that, it was quite something to see.

I’ve got my suspicions as to why that happened, but what was the mood that you read in the room? And what do you think instigated that response?

Well, I wasn’t expecting it. I don’t know. I haven’t interrogated it. I just thought it was a great moment for Helen is what I thought.

Her presence there, I think, definitely played a part in the response. But the strength of the film, and I think also why the audience reacted that day, was to what I suppose could be called failure. You’ve got a much more powerful film because of the way events unfold. I think it has a much more moving effect.

That has more to say. It has plenty to say, that film. And sometimes films can have plenty to say, but getting them to say it clearly can be a bit of a trick that you never quite solve the Rubik’s cube of. But with My Year with Helen, I’m happy. I walk away from that film, I go, “Whatever that film is, that’s it,” because it does speak really clearly, really strongly about something. You’re taken right to the doors of the all-boys club. The big, global, actually nuclear-powered all-boys club. And you can see how it works.

The impassioned arguments for a woman to head the UN aren’t made in the abstract but in the context of “this time it’s bloody going to happen”. These aren’t academic thoughts. This is a live campaign, you become invested in it as you watch it, and when those hopes are dashed, it’s crushing.

It’s a secret process, and the agitation had helped open the process but only at general assembly level. And then, well, you hear “women don’t apply”. All the old ones, “women don’t apply”. And then they really worked hard and there was a 50/50 split, male-female in who was going forward publicly for the job. With the open dialogues, it was clear that there were several candidates who could have done it. And Helen was by far the winner in that particular forum. It’s all in the film. And then there’s a new obstacle which is, “Oh, yes, but we have to have the best candidate.” So the bar rises somehow. And I looked at all that and I thought, “I’ve heard all of these things before for years and years and years. There’s nothing new here. ”

So the huge institution is just the same as the smaller ones.

Well, yeah. I think you could apply it to the White House. You could probably apply it to Congress. You could apply it to the Beehive.

Those forces reflect the general global position of women. I’ve never been particularly interested in female leadership, to tell you the truth. I’ve been surrounded from the time I went art school in Canterbury with very strong, opinionated women who’ve been taking an equal place, in terms of the conversation and how things pan out. And when Helen was prime minister, it wasn’t just Helen who was prime minister. There was a female governor general. There was a female leader of the CTU and there was a female attorney general.

And even outside those institutional roles. Like Heather Simpson. It was a very strong outfit.

That’s right, yeah. And I’m glad my daughter was born and grew up through those years, actually, because we could take it all for granted. But when you get over to a place like the UN, you sure as hell see how it all operates. It goes on behind the closed doors, because you get behind the scenes and then it’s like climbing a mountain. You go up the ridge, and you get to the top of the ridge, and there’s another ridge. Well, it’s kind of like that. You go in through the door, and you get behind the scenes, and then you find there’s another “behind the scenes”. And then you push through there, and there’s another “behind the scenes”. And I think that’s where the strength of the film lies.

It must have been fascinating when it reached this stage, where the doors are closed, there’s a media scrum, there’s media conjecture and experts, but no one’s got the faintest freaking idea what’s actually going to happen.

That’s right. I mean, this is a three tribe, ethnographic film, really. That UN building, that beautiful building, that’s the waterhole, right? The animals come through, three tribes: the diplomats and politicians; the press, who want the true oil and they’ve got sources because they can’t get it, officially. And none of the diplomats or the politicians want to talk to the press. Then there’s this other tribe, which you could loosely called civil society, lobby groups of all kind who are desperate to talk to the press. Do the press want to talk to them? No! See, so there’s this weird little dance goes on, which is apparently the information age

And in that environment, people who use social media like Twitter are in the ascendancy now, for better or for worse, because they can cut through all of that themselves. And I mean, Helen is a politician who does that, which was partly why she was doing so well, because she understands social media.

That’s illustrated when she’s in the back of a car explaining “You can just set up Instagram like this.” And it’s not what you expect, not the perceptions of well-oiled political machinery. One could ask “Where does she ever find the time to do that?”, but I suppose that the victory of social media is in stealing moments.

Yes. So if Helen’s sitting, waiting to meet the King of Spain, she won’t just be sitting there. She’ll be doing her homework. And if she’s on a panel and there’s five people speaking and she’s one of them, she’s not just sitting there nodding and smiling and looking at the audience. She’s listening but she’s doing her homework. And at first, you think, “Oh, she’s a bit rude,” but actually, she’s incredibly efficient.

So, Helen arrives in Sydney. She’s been on planes for 36 hours, really, to get there because she flew from Chicago, and her plane was delayed. Helen arrives in Sydney at 10:30 in the morning, Sydney time. We take her up to her hotel room. By the time we’ve sort of checked that the hotel room’s nice and all the rest, Helen has already taken a photo out the window [laughs], a good one, and tweeted it.

We were watching her presence over those few days in Sydney. It was ferocious.

The thing about Helen Clark is she is outstanding. She’s been on the Forbes list of most influential women in the world for absolutely ages. She was in there from when she was a prime minister. When she went to the UNDP, she went down to number 61, out of the 20s, and she built herself back up and she’s now 22. She remains 22 in the list of most influential women in the world, according to Forbes Magazine.

It’s a fascinating to be in that position without an office as such.

That’s right. And she is influential. Forbes has got all sorts of ways of working that out. And that’s nothing to do with personal wealth. So she couldn’t be more Kiwi in the way she operates. I can’t help thinking that if she was a man with those kind of credentials… if her name was George, if she was George Clark, which is her father’s name, she might be better known somehow.

I think we all go, “Oh yeah, she’s great. She’s Aunty Helen.” And I, for one, can say that I took her for granted. I’m a critical person so I have my own thoughts about all politicians. So I’m not just a fan-girl talking. But having spent a year trying to keep up with Helen – we could’ve called the film that – I just have great admiration for her.

And I think that goes back to that standing ovation. That’s really what it was about. People going, “Holy cow.”

I mean the only tribalism that would’ve been in that room that day would’ve been some liberal tribalism, some gender tribalism, and some expat Kiwis. But even those things working together were not enough to create that response. It was actually what was coming off the screen, not just what people had brought with them that day.

And also it lit a fire. The film has a mission. And like Bill Gosden said in his programme notes, it’s good that we’re making a documentary about the dreadful situation, actually. That you can look locally and go, “Humankind, what are we doing?” Where 51% of the globe is women and if we just empowered women, if we just did this, we would slow down population growth because educated girls don’t have as many babies. We would add such a huge resource to everything on the planet, rather than marginalise in every area what women can do.

I mean you’re never as marginalised as the moment you become a mother. That’s in the film. When that was said in a meeting in Botswana, it was very early days. We weren’t funded. We were just finding out if there was a film there. And when that was said, I thought, “There’s the film.” That is actually where the film lies.

As you recounted at a Q&A in Sydney, it sounds like the genesis of the film was basically, “I’m going to go and shoot Helen Clark and see what’s happening,” in a way. “There’s got to be something going on there.”

Yes, sort of “why is she perky?” [laughs] when it’s seems everything’s getting more and more out of hand out there in the global village? And Helen was energised because she saw how the UNDP, the development arm of the United Nations, is actually the way to prevent war. The more you can put into helping a country that’s down on its luck so that the political conversation can stay a conversation and not descend into war, all of that does work. Unfortunately, I think now we are going to witness a real change in the UN, in terms of down-scaling development. UN watchers are watching all that with different degrees of concern.

Just as – I was going to say, the brakes being put on in the United States bureaucracy, but it’s more like that car’s being deliberately driven off the road. That’s the same process that’s going to be happening in the United Nations, albeit a little bit more slowly, right?

Yeah, and all the money will go into the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, which is as one of the press commentators says in the film, “A race to the bottom.” Well, Helen’s not on a race to the bottom. I mean, it’s going to be very interesting to see what she does next.

There are a couple of specific moments in the film that stood out for me. One’s really small. One’s quite big. We’ll start with the small one. That’s watching her in what I think is a reception at the UN. She’s having a drink. And, if I’m not mistaken, she’s drinking beer out of a wine glass. Is that correct?

Yes.

Now, is that because a woman can’t be seen to be drinking beer? Or does she just prefer to drink her beer out of a wine glass? So a few things were going through my mind as I watched that scene. I got a bit distracted by that.

I don’t know.

Maybe it’s just not the thing to do?

No, I don’t think it’s that. Is everybody else drinking out of bottles?

I think they might be, yeah. Is that something you have to do as a woman do you think?

Well, it’s probably not that acceptable to drink beer out of a bottle, whereas the glasses there must’ve all been for wine. It could be that Helen just prefers to drink out of a glass. I mean, personally, I do. I don’t like drinking out of a bottle. So I never questioned that, but it’s interesting.

The other is the supreme moment of silence that you capture. I think many documentaries use a moment of reflection by their subject to say more than their words ever could. What’s the feeling like in the room when you’re rolling a camera and the subject just has that kind of inward moment?

Helen does thousands of interviews in a year, so I didn’t want to make our times with Helen interviews. I wanted to make them into conversations.

Otherwise, she just reverts to the familiar, right?

The regular access to Helen through the film is the key. Because every time we do it, we’re in a different zone with her. We kind of enter where she thinks she’s up to in the race. And I can’t even call it a race, I have to call that a process, don’t I? And so sitting there with her, I would get the cameras rolling, get us all settled and then not ask anything, just sit there and let Helen start. So hence my non-sequiturs like, “What a thing, eh?” [laughs]. I would try to say enough of. Helen found that in varying degrees, a bit “filmmaker-y cute” probably. A bit kind of tedious, a bit funny.

She knew I had a plan but she knew that some of my stupid questions were a bit cute and I would have to ask her the same questions a month separate. And Helen forgets nothing, so she’d know she’d already answered that question if I was asking her a question.

I can just imagine those looks that crossed her face.

Helen looks at her watch a bit [laughs]. You see her do it in the film. She goes, “Right, well I think you need to be somewhere else now.”

I love all those mannerisms so much.

It was a mad, crazy project. It was deeply challenging, it drove me nuts. I had wonderful support – that film was made by two women and I had Catherine Madigan who’s the co-producer and also the line producer and everything else that I wasn’t, Catherine was. So we had a crew of two.

Occasionally, we were lucky to have Ken Saville, our sound guy travel with us because I know if I’ve got Ken there, we will be able to hear what’s said at the party. The one where Helen’s drinking beer out of a wine glass. Well, we could go to those kind of events with an American, with a local soundie and I couldn’t be sure we’d have it, but with Ken, he just gets it. Sound is the really hard thing. And especially if you’ve got a subject who won’t wear a radio mic.

Helen would wear a radio mic when she was in a room with us on her own, which kind of defeated the purpose really but the idea of a radio mic is so that we can back off in crowded situations and stay out of her face, but Helen was always protecting what someone else might say to her.

That’s a lesson that’s been learned, somewhere along the way, isn’t it?

Yes.

You touched on the “Aunty Helen” thing before, because obviously as New Zealanders, we’ve all got a relationship with her and for many people, it’s super negative.

Yes, so it’ll be interesting to see the film at Civic, won’t it? Because our attitude is so much more complicated than it is in Australia or than it is globally.

Yes, absolutely. When my review went on Facebook, some of the comments were what you’d expect – like, some were horrendous. And I just wonder how you would like New Zealanders to relate to this film with that in mind, that we already have these biases in place?

I don’t have a wish list. It’s out there, the film stands as a social document of a particular time and place with a particular person. I think part of the social document is how vociferous comments can be as soon as you’re talking about female equality. We’re not talking about superiority here. It’s actually just equality. We’re only talking about humans’ rights and equality when we talk about female equality. And I’ll tell you what, on my Facebook page, whenever I’ve said anything that roughly mentions the F word – I mean feminism – I get the vociferous negativity. There is an army of people who feel perfectly happy to say what the hell they like, and I think that poor stand is a social document too, alongside the documentary, because that’s what it’s about.

Making that response visible is an extension of the film?

Yes. But I think part of the problem that we have as female practitioners, in film land or whatever, I notice that if a high profile male colleague of mine does a high profile thing, that gets some criticism, let’s say vociferous criticism, there’s a whole army and tribe that races to their defence and shuts it down on social media.

And I, personally, haven’t ever had that happen for me. Whenever I’ve been attacked or a film of mine has been attacked, there’s no army. There’s no gang. There’s no public gang that’ll race out and support me. It’ll all happen in little whispered corners like, “Gaylene, I’m with you,” but they won’t go public. So I think that women don’t have gangs because we women we don’t want to get shot at.

Because the opposition is so much more vociferous and nasty. When I’ve made a film here that hasn’t exactly clicked with the audience, there’s a lot more public attack than when I’ve made a film that’s worked. And then I started looking at how happy people are over the years, so I’m going back to Merata Mita’s films. If you look at the way female work gets discussed and criticised, you can’t afford to make a mistake.

So, I’m glad I’ve lived long enough to be able to put all that in perspective and not take it personally, and I’m glad that I’ve been able, as a filmmaker, to survive that, quite frankly, because there are plenty of people, male and female, who, when their films get done over really publicly, it is psychologically damaging. You do get under the duvet for a while. It is hard. You do need your tribe. And if you don’t have a tribe, it’s very hard to get up and do it again, and it’s very hard to get the money.

I interviewed a female filmmaker years ago, her debut film was about to release. I think she was already affected before the release going, “If this doesn’t work. I’m not going to get to make another film,” and both that sort of I don’t combination of fear and awareness was already starting to embed.

This is something that I’m very well aware of and the Film Commission has become aware of. I was asked to front a small scholarship for women directors last year, and they said, “You can define how you want to do it.” And, of course, the assumption is that you look at someone who’s up-and-coming. Everybody’s really groovy when they’re making their first film. Everybody.

I said, “I want to make this scholarship only available to people who’ve made a feature, who are contemplating a second feature. For women who’ve made a feature, who are contemplating a second feature.” And they said, “Well, there may only be 10 people eligible.” And I said, “Well, so be it. I’m busy.” Right? Well, there were 30. And more and more people came out of the woodwork, and it helped focus the fact that what happens with women is women tend to make lots and lots of short films really successfully, because women tend to be less confident. But we like to know we can do something before we do it, which is nuts. Nuts. Get over it.

You can’t make films for practice and the audience is in the cinemas. The audience is for feature film, and all you’re doing when you’re making short films is making short films other short filmmakers and festivals, really. And women, more than men, have to get into making the features younger. Invariably, now, I’ve noticed the pattern is that women make short films to;; they’re at least 30, 32, 33. They start making their first feature round about when they’re 30, 35 if they’re lucky. And then they’re ready to have their babies. There’s all sorts of pressures then on how to get that second feature made. And surviving the slings and arrows is really hard, really hard.

We don’t have rah-rah gangs, “Gaylene! Gaylene! Gaylene!” Haven’t heard it. Probably would laugh. Probably. There’s always room for one. There’s always room for one, and every year there’s room for one who mirrors the problem. So there’s always going to be a star, a woman star who comes out of New Zealand and is the star, one that hides the fact that everybody else has got these difficulties. I’ve been really lucky because I’ve managed to stay home, have my family here. I prefer making my films at home, and I’ve been able to find a little niche that’s allowed me to do my own work, my own way.

If I had a different name for my film company other than Gaylene Preston Productions, I would call my film company Macrame Movies [laughs]. Because I’ve found a way to be able to be a mother, a good daughter, a member of my community, and make my movies. And I’ve been able to sustain this – I’m touching wood – for a long time. Come the slings and arrows, come what may. And now, with my My Year with Helen, I was going, “Here you are. There’s one.” It’s a living document. If you’ve decided to declare war on me or Helen, so be it. We’re both used to it.

See ‘My Year with Helen‘ first at the NZ International Film Festival and in general release from August 31.

Flicks Editor Steve Newall travelled to Sydney Film Festival as part of Vivid Ideas courtesy of Destination NSW.