Veteran BBC Journalist Kate Adie Talks ‘6 Days’ and the Art of Reporting

Toa Fraser’s 6 Days tells the true story of 1980’s Iranian Embassy siege in London. Notable for being among the first events of its kind broadcast live on TV, the siege was covered by renowned BBC journalist Kate Adie, played by Abbie Cornish in the film. Adie attended the NZ International Film Festival for the NZ premiere of 6 Days – Flicks sat down with her to talk journalism then and now…

FLICKS: 6 Days is hardly the first film to utilise on-screen journalism, in one fashion or another, to move its story along. As a journalist, are there things that you find humorous about how journalism is portrayed in films?

KATE ADIE: Generally, I have to say, there’s always a complaint by reporters that they never quite get the atmosphere right, particularly in newsrooms. It’s always far more glamorous than newsrooms usually are.

The second thing, as well, is that in 90% of sort of films that you see, and then TV dramas about journalism, there are always too many coincidences. Everybody appears to be told the right information at the right moment and then people act immediately on it. It’s all usually a little too perfect. Journalism is a messy business, usually. Reality is more complex and people are very unpredictable. And that never quite comes over.

The curious thing watching this [6 Days] and also remembering back to it is that, not uniquely, but very, very unusually, this was a time when journalists were actually present when a news story literally exploded in front of them. And that is so, so rare. A lot of fiction, a lot of feature films, show this happening frequently. It is extremely rare.

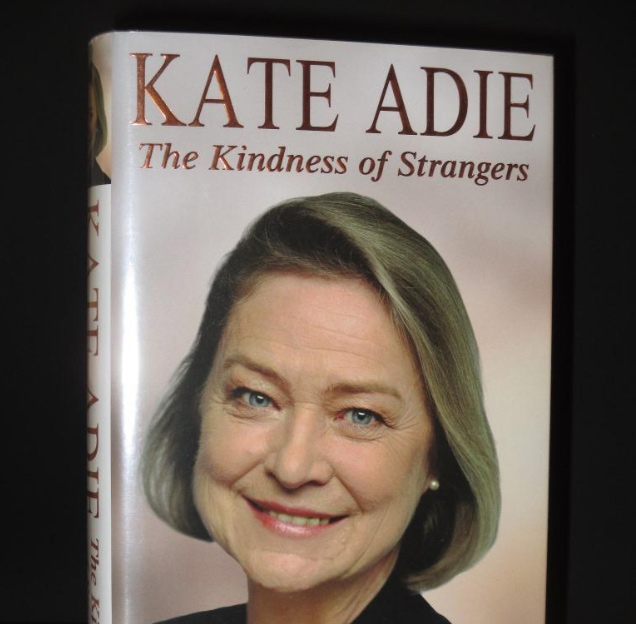

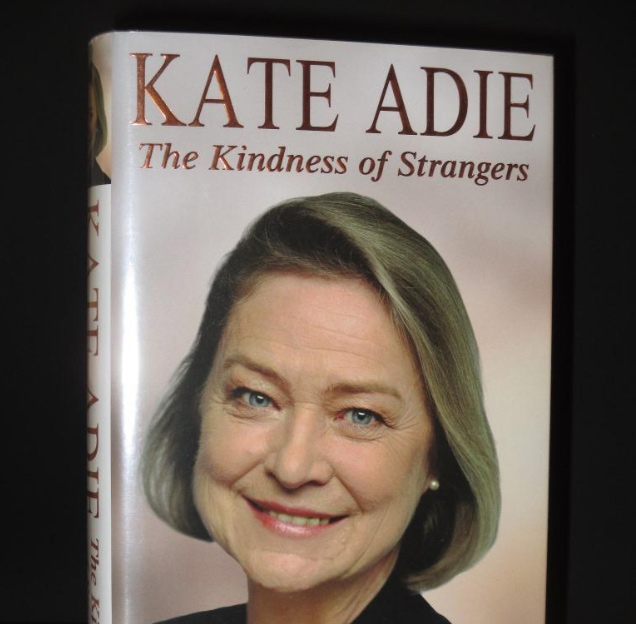

When I came to write my autobiography some years ago, I nearly called it what so many people had said to me over the years, which was You Should Have Been Here Yesterday [laughs] because you always turned up after the event because journalists don’t have a crystal ball. Nothing is predicted to them. They don’t know vastly more than most people. And for something to happen when you’re on the spot and you actually have a camera and can go live, well, it is so unusual.

That is why, I think, so many people remember having seen the Iranian embassy siege being ended on live television, that the assumption’s been since that, “Well, that must happen everywhere.” No, it doesn’t. So in a way, this film shows something which was so unusual and it really gets it. It really does.

As well as those humorous or maybe glaring things that stick out about how journalism is portrayed in film, do you think there’s a danger for the wider public about how they see the art of journalism coming across on the screen?

Oh well, look. I mean, everybody who watches a movie about hospitals, it’s full of handsome doctors and beautiful nurses, and everybody saves lives. Come on, it’s the same with journalism [laughs].

I’m totally with you, but I think journalism is more present in our lives.

Here I will actually indulge in being an ancient person. When I joined the BBC, I joined local radio. I mean when dinosaurs roamed the Earth. And when I went to work in the local radio, which was my first job, journalism was not seen as at all romantic or even fashionable. I remember in my very first job some years later as a regional television reporter doing local news, I remember the news editor when we said, rather pathetically, we little reporters on that regional station in Southampton, “Why aren’t our names in the Radio Times?” which was the publication of TV programmes. “Why aren’t our names there?” He said, “Because you don’t matter. You’re just the legs who go there and the lips that speak it.”

We were minor creatures and journalism was regarded as a somewhat grubby trade. We were called hacks. There was certainly none of the personality-led, or glamour, or celebrity world attached to journalism. There might be one or two more famous journalists who were working on television, who were nearly all men. But they were distinguished for the sort of stories they’d done, and there was none of the coverage, which began to creep in about – let’s calculate – 30 odd years ago, etc.

When television became more glamorous, more popular, more widespread, to be perfectly honest – more people were getting tellies in the bedrooms and getting colour telly – it became more prevalent, and the glamour began to slide into journalism. I remember being interviewed, oh, 30 years ago, and the rest of the news room said, “What are you doing an interview for?”

Who’d want to talk to…

Who wants to talk to a hack? Well, the argument was that I was one of the very, very few women working in TV journalism and doing hard news. In other words, sort of crime, politics, terrorism, that sort of thing, rather than knitting and women’s programming. So there was a sort of, “Oh, really?” Now that has grown since. So I think that’s the sort of answer to your question about how is journalism portrayed. It’s slid into this great world of entertainment and celebrity, so much so now that quite a number of news readers have agents.

Inconceivable when I first started!

I bet.

As one of my colleagues said – Michael Buerk, who’s a very well-known BBC journalist, same age as me. We worked together for years. He once said, “Who would want to talk to people who are paid for reading out loud?” which is the definition of a news reader. So, it has become a much more in-your-face sort of profession, so much so that there are lots of young students who think it’s very glamorous being a journalist.

And I have to say, first of all, today there is a lack of jobs. The media haven’t so much money these days. And secondly, if I think of the glamour, yes, there is a spurious glamour, and it’s a terrific job to have if you’re interested in the world and meet people. But when somebody said, “How would you sort of talk about the circumstances of reporting?” I said, “Bad food, sleeping on floors, fleas, quite a lot of unpleasant diseases in certain places, great deal of hostility sometimes when you arrive in places where people are terribly upset, or angry, or violent.” It’s a job about people, about the world. It’s about reality. The idea that you float around looking cute is certainly not the case.

Going back to the siege itself. We see that the live coverage was used as a tool of propaganda almost by the British government.

In what way?

Didn’t Margaret Thatcher want the country to see the raid?

Oh no. Mrs. Thatcher had nothing to do with it at all. That’s a bare piece of nonsense. It was a major event in central London. The world’s press was there. Mrs. Thatcher had absolutely zero connection to anything going on in that way. There was no political manipulation, or influence, or contact of the news rooms.

I didn’t mean in terms of the coverage, but I meant that she wanted the raid to happen in view of people.

No, she didn’t. She didn’t. I might tell you, having interviewed Mrs. Thatcher a number of times, Mrs. Thatcher was a woman who was relatively indifferent to television. She was never interested particularly in turning up on it herself. She never watched it. I actually knew that from the housekeeper at Chequers, where they used to spend weekends. She never used to watch television. She was a woman totally uninterested in her own sort of presentation on it and had to be sort of coached and chivvied towards it.

And from the point of view of the press, there was no, as it were, mechanism whatsoever for interfering with anything that was going on. The fact that it was going to turn up in public was not one of the ways that people approached it. It was inevitable. You have the world’s press camped a hundred yards away. There was no way of it being a secret.

It’s very, very strongly intimated in the film.

Well, it’s intimated that it would be seen because of people like Willie Whitelaw, who is played by lovely, lovely actor, Tim Pigott-Smith, who sadly died recently, whom I knew very well. And I also knew Willie Whitelaw. And Willie Whitelaw was a straightforward pragmatist, who was the home secretary, straightforward and who wouldn’t even have given it a second thought. Television would be there. That’s that. The army is a much more interesting one because these days the British SAS have a kind of worldwide reputation. They were almost unknown at the time. People have forgotten that. They were usually used for covert surveillance. We knew also they were involved in special ops. They were a sort of shadowy outfit.

By their nature, unknown?

Yes. There was no public profile for the SAS in those days at all. It was a sort of, oh yes, there’s those strange outfit, does odd things, etc. It was operating in Northern Ireland but mainly on surveillance and special ops abroad. This was the first time they’d ever been seen in action. And so, in a way, nobody had conceived of the impact that it made. Nobody. I don’t think that that was realised. I don’t think it was realised by the army themselves.

I mean, I’ve talked to Mike Rose who’s pictured in the film – he was a very handsome army officer also portrayed as very handsome [laughter]. And I’ve talked to Mike Rose, and Mike Rose would have said, “No, we’re far too preoccupied with doing other things than to whether worry about television.” And so I think if we approach it from today’s views of the impact of television, it’s a bit different. But if you think back to 1980, nobody had given it much thought.

So I guess we’re drawing conclusions in the present based on what the impact we now know that coverage has worldwide.

Indeed, indeed. But then I even was avoiding the fact that it was probably the SAS. I only knew it would be them because I had a friend who was in the SBS, which is the Navy and Marines Special Service. And that was just a coincidence, and I knew a little bit from him. And it was a little bit about the nature of things, and I’d worked in Northern Ireland as well. But certainly, nothing like people would have as a background today.

This is a very complex question, but is there a way that you can sum up the impact of the live coverage of the event in the geopolitical landscape that we have today?

Very difficult because I’ll tell you the major difference today as to what happened, if I look at it at the time. It brought the SAS into a prominence and gave people the idea, rather dangerously and they would say so, in a sense, is they would be the answer to everything.

Right, “send them in” if there’s a problem.

Yes. That, I think, has been discounted rather in the last few years. People are a bit more realistic. Secondly, it gave also the people the idea that we did live news and it all happened in front of us, which is completely erroneous. But 24-hour news these days likes to give the impression, but still has trouble and difficulties because of how human life works out in doing that, but likes to give the impression that it’s all happening. Those are the two sort of things connected to that.

If I look at today and say, “Where does it fit?” it did set a very public kind of marker that the British government doesn’t negotiate and is prepared to take what action it can do, which may involve ultimate force and will go in and do it. That hasn’t changed and I think that’s still at the back of people’s minds about quite a lot of things that happen today. The complexity, though, of things today adds another dimension, and I did think of this when watching the film. Today you will probably have the terrorists take in their phones and use them to transmit images. We have now got all sorts of broadcasting, not just the officially-approved ones, and we have to deal with that, which is a very big ethical question. And so you can’t quite see it through today’s eyes.

Yeah, so if we look at the 6 Days scenario, the siege, then the terrorist manifesto, the list of demands, and the state of the hostages would be something that all media would be carrying, as supplied by terrorists’ own digital devices, if that was the editorial choice.

There are enormous ethical questions. I came to look at this when I wrote a book some years ago about dangerous jobs and one of them was hostage negotiator. I’ve known people who’ve done the job over the last 30 years, which is a terrible business. And I think that hostage, and kidnapping, and siege stories are some of the worst that you ever have to cover. They’re the worst in one specific way and that is that the people at the very heart of it, the people whose lives are threatened, are vulnerable and you have to keep this in your mind’s eye all the time while reporting.

And you are probably in many instances going to be asked not to deliver certain information which you may have acquired completely legitimately, for example, that one of the hostages is gravely ill or that their identity is something which the hostages haven’t yet discovered and whatever. You are asked to keep schtum about certain things and you have to balance that with getting the information out, which keeps the public properly informed. And the whole thing is a terrible set of tensions, and all the time you’ve got in your mind that these people at any moment, if you do something which is improper, could endanger their lives. Now, very few situations exist in which journalists have an effect, but this is one of them. And so I think it’s one of the most tricky situations to cover, ever.

See ‘6 Days’ first at the NZ International Film Festival and in general release from Sept 7