Back from the Grave

Welcome to this new, longer and potentially more indulgent incarnation of The B-Roll, a tiny column I started for the now-sadly-defunct street press Volume. Some background: the column (a glorified side bar, more like) had a brief 12-issue run in the mag and was literally tiny: 100 words to be exact. It was the result of Volume editor Sam Wicks and I sitting down to hash out how we could improve the film page, i.e. turn it into something that was something more than an afterthought in a predominantly music-oriented publication. So I offered this idea of a small space where I’d be free to write concisely about films I’d seen that were far removed anything else that was on the page. It was an attempt to ‘personalise’ things so it wasn’t just another film review page.

And personal it was – to the point that it pretty much reflected what I’d pull out from my stash to watch in my own spare time. Some of the films covered were recently released DVDs which I wanted to talk about, others were just films I wanted to write about period, out of self-indulgence and devoid of any commercial interest and motivation.

There’s a sensible rationale for all this. When you’ve been reviewing films professionally for almost 10 years, burnout and disillusionment almost unavoidably set in. The latter figures especially when you’re subjected or forced to watch dreck like Battleship week after week for the ‘job’, and when you’re attending screenings, where you’re in the mindset of a ‘job’. I can’t speak for others, but this aspect of film reviewing for me has over time become less glamorous, enjoyable and cushy than people might expect. Free movies are great, and I’m not about to call it a day just yet, but sometimes it’s such a drag to catch a screening of the latest Tim Burton flick at 6pm that you’d rather not bother. (I’m getting to my point shortly…)

For the longest time, when I realised that burnout was inevitable I justified doing a job as it would basically mean I could afford to acquire what I actually wanted to watch. If I endured Wrath of the Titans and churned out a couple hundred words on it, it meant I could probably pick up that Fernando di Leo Blu-ray set that I’d had my eyes on. It’s about maintaining some kind of sanity and balance, and in terms of ethos, I’ll approach this blog in a similar manner (as I previously did with VHS Vortex for Real Groove [RIP], or currently do with the film stuff in Barker’s 1972 mag), and hope that it will be of some interest.

I guess a lot of what I’ll want to do with this blog, or at least try to, is to address the things I brought up in The Curse of Hype back in March: the hunt, the discovery, the richness of film history. It’s a great, opportune time for us to seek out and champion lesser known films and see what’s really out there beyond opening day. As prints are being phased out and destroyed in favour of digital and more and more emphasis is placed on the bottom line, countless films will be forgotten and never see the light of day again. A fraction of what’s come out on DVD will come out on Blu-ray, as a fraction of what was released on VHS made it to Laser Disc and DVD and so forth.

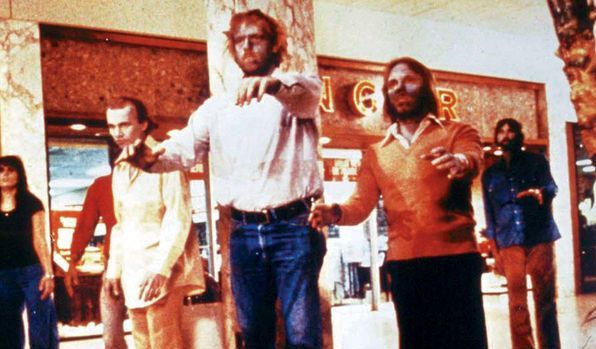

What should you expect here? It may involve me revisiting and re-evaluating films, picking stuff from my unwatched pile and watching it blind, raving about something I saw last night that blew my mind, spotlighting a director/genre/person/thing, or maybe using a recent news item as a jumping point (as I have below). As for the availability of these films, I refer you to lmgtfy.com, but seriously though, where possible I’ll try to mention where you can buy them, or warn you if it may involve trawling through the VHS bin at salvo shops or maxing out your credit card on eBay (seriously though, Google is your friend…). Also it goes without saying that anything covered here will reflect my tastes, so if you find certain genres/elements over/under-represented here … sorry.

Okay, so picking up where things left off… the last B-Roll I did before the plug was pulled on Volume and it could be published was on William Friedkin’s ill-fated 1977 film Sorcerer. Friedkin (The Exorcist) recently sued Paramount and Universal over ownership rights of the film, a then-costly remake of Henri-George Clouzot’s ‘53 French classic Wages of Fear that hasn’t really been treated all that well over the years – it certainly deserved better than the crummy DVD Universal dumped onto the market way back in ‘98. Though a massive failure in its day – a combination of being up against Star Wars, a weird, head-scratching title and a bit of how-dare-he from critics – Sorcerer’s rep has grown over time. Here’s one immensely underrated work that’s as good as, if not better than the original.

Only a director of Friedkin’s ballooning ego and ambition would choose to follow up making one of the greatest horror films ever with the most difficult shoot possible in his career. Completely shot on location in the Dominican Republic, the film, a near-Herzogian yarn of trucks carting unstable nitro across treacherous jungle terrain, is a sweaty, tense, dark, even hallucinatory masterpiece, with an ominously bubbling Tangerine Dream score, a memorably haunted performance from Roy Scheider and incredible, logistically nightmarish set-pieces that remind you how powerful seeing things as they are, unaugmented by any digital trickery, can be. Sorcerer is a personal favourite of Friedkin’s, and one hopes a Blu-ray remaster of some sort will be forthcoming once the legal wrangles are done with. Check out this fantastic, anecdote-packed Q&A below with Friedkin from the American Cinematheque screening of the film last year (it’s in five parts):

Perhaps even more neglected is the film Friedkin made right after Sorcerer in ’78: the lightweight caper flick The Brink’s Job. I first stumbled on to it on Sky’s MGM Channel (plenty of rare gold there), and it’s quickly become one of my favourites, a reliable pick-me-upper if I ever need one. As far as I am aware, the first official DVD release actually came out in our neck of the woods from Shock as part of their very cool MGM line, though the film is now easily available from Universal’s MOD Vault series and Netflix Instant if you live in the States.

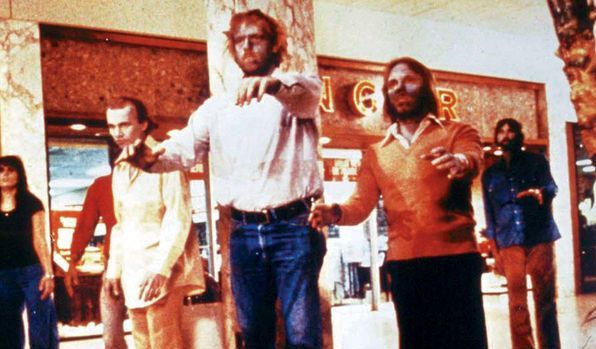

Like Sorcerer, The Brink’s Job didn’t perform and is now something of a blip in Friedkin’s filmography. But damn if it isn’t one of the most supremely enjoyable things he’s ever done. Working again with Sorcerer scripter Walon Green to adapt Noel Behn’s book Big Stick-up at Brink’s, the film is based on an infamous, real-life 1950 Boston robbery which prompted FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to hilariously surmise that it was the missing link between the Communist Party and organized crime. In reality the heist was really the work of local boys, in the film led by Peter Falk, who plays Tony Pino, a fast-talking, fast-fingered small-time thief whose team consists of wonderful character actors like Allen Garfield, Peter Boyle, Paul Sorvino and Warren Oates in a standout role as a former Omaha beach vet who lends his technical know-how. Gena Rowland’s in there too, as Pino’s wife.

Friedkin, who took over the project from John Frankenheimer, was inspired to make a comedy caper in the style of Mario Monicelli’s 1958 Italian classic Big Deal on Madonna Street, and The Brink’s Job works a charm as homage, while its breezy tone compares favourably to other ‘70s caper films like The Sting and The Hot Rock. The heist scenes are not exactly intricate – part of what makes it funny is how ridiculously lax security was once for Brink’s, a world leader in cash transportation – but Friedkin’s finesse in pacing and staging ensures there’s always suspense where required. The cast overcome their flawed accents simply by being a delight to watch, embodying the working class sense of neighbourhood the film so earthily portrays. It’s telling how the central heist itself never pop outs like The Big Climactic Sequence, playing more like another, almost-mundane moment out of the characters’ daily lives. The film’s beautifully realised period look received an Oscar nomination for art direction and its shooting on various locations where the robbery occurred adds a touch of authenticity.

Again, like Sorcerer, many bizarre events plagued the production, the most notorious of all being the gunpoint theft of unedited reels for a $600,000 ransom. A detailed account of the behind-the-scenes stories can be found in Paul Sherman’s book Big Screen Boston: From Mystery Street to The Departed and Beyond.

Soon: maybe a reappraisal of Friedkin’s The Guardian and Jade…