Parallel Mothers continues Pedro Almodóvar’s passion for films about family and femininity

Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar has always shown a deep respect for the women at the heart of his stories. Cat Woods discusses his new film Parallel Mothers in the context of a rich body of work exploring feminine history and desire.

Parallel Mothers

Love, lies, women, sex, exploitation, violence and family. Pedro Almodóvar has never shied from the raw, real, fragile essentials of existence, and in Parallel Mothers he has again crafted a beautiful, sometimes horrifying investigation into what it means to be part of a family. It is a profound question: terrain he has mapped before in All About My Mother, Pain and Glory, and Volver among others.

Almodóvar has always respected and revered stories of family, and even more so, the women at the heart of them. His women are nuanced, flawed, both sympathetic and cringeworthy in their relatability. They are ruled by desire and the guilt they feel for it: whether the objects of their longing are men, women, jobs, autonomy; children, or emancipation from child-rearing.

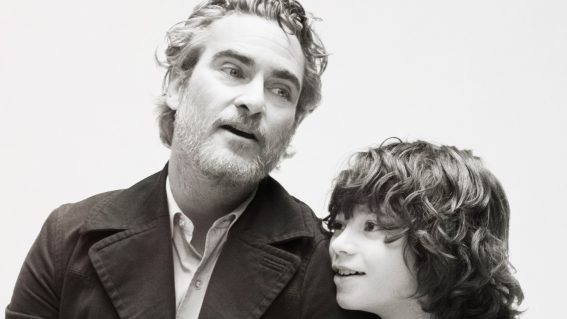

Over seven films since Live Flesh, Penelope Cruz, Almodóvar’s long-time collaborator, has been a mother, a daughter and the object of desire. At the centre of Parallel Mothers is Janis, who is played by Cruz—and is as ever divine to look at. The camera is drawn to the sculpted shape of her cheekbones, her big, dark eyes and long, tawny limbs. Cruz is—like the film’s gorgeous 70s-era, retro-chic Madrid interiors and grandly ornate city streets—utterly beguiling.

Ana (Milena Smit) is the teenage mother who shares a hospital maternity room with Janis. The two quickly form a bond as single mothers, although they are decades apart in age. Ana is petulant when sharing the room with her mother Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón de Angelis), a lovely but distant actress who in one heartbreaking scene confesses that she is convinced she isn’t naturally maternal.

This story presents a spectrum of subtleties

Almodóvar’s women are hugely critical of themselves, and Teresa bears this out in her tearful admission. Any other director might have allowed Teresa to be the tale’s antagonist: the ice queen abandoning her own child. But in Almodóvar’s world she is a spectrum of subtleties. Who is naturally maternal, and does a woman need to be the blood relative of her child to be drawn to protect, nurture, and raise it?

In one lovely scene, Janis teaches Ana to make a potato omelet while wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the words of writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “We Should All Be Feminists”. In another beautiful moment, Janis points out to a fellow mother (or parallel mother) the photographs of her mother, grandmother, and great grandmothers. They are depicted in large black-and-white portraits, reinforcing the truth that history is always part of the present.

As far back as 1999, when All About My Mother was released, Almodóvar had mentioned to Cruz his idea for a film exploring motherhood in the present day, within the context of Spain under Franco’s dictatorship and the Spanish Civil War that had robbed mothers of their fathers, husbands and sons. That the two have made that film now is serendipitous. Cruz has since become a mother, embodied many women for many directors, and returned to her frequent and longstanding collaborator with the readiness to portray Janis as the magnetic link between Spain’s bloody history and present-day Madrid.

Almodóvar has long interrogated the repression of women

Under Franco’s reign, women were expected to be mothers and to primarily occupy the home in very traditional, gender normative roles. Almodóvar has long questioned the impact of historically, culturally embedded repression of women, and the pressures of history, society, politics and religion in forcing women to be ashamed of their natural desires. The emergence of Spain’s modern character, and the reality of the nation’s traumatic history—still fresh in relative terms—give a gravitas to the Ana-Janis story.

The plot twists and turns in Parallel Mothers aren’t as alluring as the impact of the film’s dramatic interpersonal relationships, especially drawn-out tensions revolving around what Janis, Ana, and the father of Janis’ child will do once they learn what Janis knows. It’s a powerful thing for our protagonist, to be the only person who has the facts and can choose to reveal or conceal them.

Almodóvar has again worked with cinematographer Jose Luis Alcaine (Bad Education, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown) to capture his characters in close-up with enormous clarity and they appear, at all times, beautiful. Everything is lit evenly, glamorously, with a sense of reverence for women and in particular the femmes fatales of the 1930s and 1940s.

Parallel Mothers features another beautiful score from Alberto Iglesias

Another repeat collaborator, Alberto Iglesias (All About My Mother, Talk To Her, Volver, Broken Embraces, The Skin I Live In, Pain and Glory) has composed a dramatic, string-heavy orchestral score that verges on haunting, but has the momentous drive to edge you closer to the screen in trepidation and wonder.

There is the feel of a high-end telenovela in the glossy, bold-hued warmth and drama of the film aesthetically, but with none of the TV genre’s soapy superficiality. Almodóvar has created what might be his most accessible film yet—neither glaringly camp and overtly sexual (Kika), nor repelling viewers with rape, vengeance, and entrapment (The Skin I Live In).

Almodóvar ends the film with a quote from Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, which is printed in both Spanish and English. It strikes to the heart of Parallel Mothers. It feels poignant now, too, as we experience the enormity of a repressed era that will one day be history. What will be true about 2022 for the children of our children’s children in generations to come? Will the traumas of our lives now be seeded through generations?

What’s certain is that the world will continue to rely upon women—to give birth, to work, to lead, to raise their sons and daughters, to share stories and to uplift one another within a world that systematically tries to stymie them.

That quote is: “No hay historia muda. Por mucho que la quemen, por mucho que la rompan, por mucho que la mientan, la historia humana se niega a callarse la boca.”

The translation is: “There is no silent history. However much they burn it, however much they smash it, however much they lie about it, human history refuses to shut up.”