Interview: Being Evel

Long before Kanye West touched the sky (and began his stage invasion career) daredevil Evel Knievel rose to fame with a combination of spectacular stunts and horrific accidents. Documentary Being Evel, screening at the NZ International Film Festival tells the warts and all story of America’s flawed phenomenon. We spoke to director Daniel Junge about […]

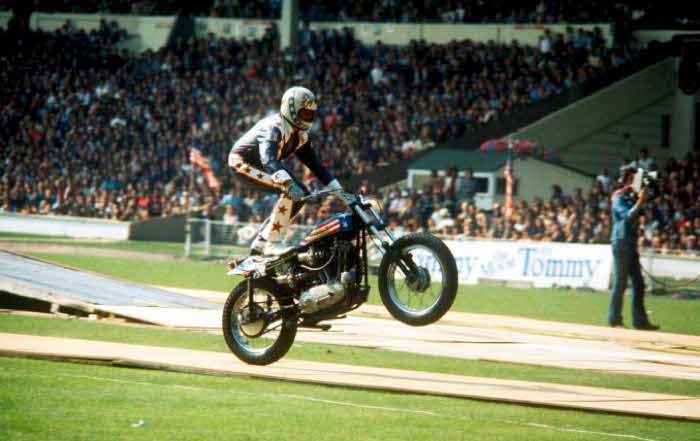

Long before Kanye West touched the sky (and began his stage invasion career) daredevil Evel Knievel rose to fame with a combination of spectacular stunts and horrific accidents. Documentary Being Evel, screening at the NZ International Film Festival tells the warts and all story of America’s flawed phenomenon. We spoke to director Daniel Junge about his film.

FLICKS: I’m in my late 30s. I kind of missed the Evel Knievel phenomenon a bit, but I’m aware of who he is, and obviously his legend traveled internationally. I guess he had much more of a presence growing up in North America?

DANIEL JUNGE: Yeah. He was definitely a global phenomenon, known around the world. He was also arguably the most famous man in America for a very short period of time in the early seventies – though his stardom had a pretty short shelf life – for a certain generation. I’m kind of at the very bottom of it at 45. Maybe people a few years younger than me might remember him, up to probably ten years older than me. That’s, like, the sweet spot for the Knievel generation. You talk to any guy – and it is mostly guys – from that era and usually Knievel’s going to mean something to them.

Can you remember watching particular stunts performed, or just being aware that things are happening contemporaneously.

I remember seeing the Snake River jump on television. It was not live, it was broadcast on Wide World of Sports the next week. I remember that, and then I remember my family that summer, we took a vacation and we went to Snake River. I remember seeing the canyon where he jumped. I also remember a few of the jumps after that, like King’s Island and the King Dome. So yes, I remember watching him on television, I didn’t attend in person.

That’s pretty awesome to go to a family vacation to the site of something so nuts.

Isn’t that crazy? It was part of the vacation. It wasn’t the destination, but it was memorable to me, but that was a pit stop.

That’s probably the craziest stunt in the film, summed up so well in the coverage showing the scale of the event. I think it’s also a great way for you to close your film as well – revisiting the location to show the utter hubris and insanity of a man that thinks he can jump a canyon.

Obviously I think the last shot of the film in a way is the ghost of Knievel finally making that jump, and that was important to me. We’re trying to find redemption at the end of the film, about a man who’s not always entirely redemptive, redeemable as a person. So the end of the film, we’re trying to remind the audience what he gave us, and so ending with the real Snake River, or the would-be Snake River jump, was important to me.

Knievel was such a massive media personality. Do you feel it was a time where people weren’t quite used to seeing the massive flaws in their heroes?

Yeah. It’s just a messy period in history, certainly in American history but I think also in global history. To have such complex characters, not just Knievel but others, come out of that period I think makes sense when you think of the political cauldron of those times. But also, our heroes are so anesthetised now, and sort of antiseptic. They’re squeaky clean and we’re kept away from a lot of the dirtiness. It wasn’t the case in the seventies. I mean, Evel’s kind of letting it all hang out there, and flaunting his flaws in some way. Now, of course, with the gift of hindsight and the fact that he’s now passed away, I think we could be 100% honest about him as a figure. So I think there’s this kind of brutal honesty we wouldn’t necessarily have about a character from now or even the last decade.

Absolutely. He’s a PR flak’s worst nightmare.

Right.

It says so much about the tenor of the times, that the main guys working with him were concert promoters, so it’s kind of no surprise that Snake River takes on those Altamont-type characteristics.

Totally. Totally, yeah.

Obviously you’re speaking to a lot of folks that worked with him. On the one hand he’s revered as a bit of a populist anti-hero. And there’s a lot of dirt on him as well. Did it take much to get your subjects to bring up the unpleasantness, or is that just woven into his larger-than-life story?

Something that was really surprising to me, is that some of the people who you would have thought been the most protective and dear about him were the most brutally honest and sometimes disparaging of him. Then some of the people who deserved to revile him were sometimes the most– I won’t say affectionate, but certainly somewhat contrite. On that spectrum, I think of his wife Linda, and Shelly Saltman. Linda in many ways is the most brutally honest person in the world, and Shelly Saltman is the one who’s surprisingly generous to Knievel.

If he couldn’t ride a motorcycle again, would he still have been the same unpleasant person, do you think, and would there have been nothing to be affectionate about?

I think if you take a cue from his early years, before he found his calling as a daredevil, you see that he’s the kind of person who’s going to push the envelope regardless, and he’s going to push people’s buttons. He probably would’ve been a fly in the ointment one way or another. I think– I mean, he did break his hip [chuckles]. He broke– depending on who you ask, he broke at least 30 bones in his body. So I don’t think that would’ve kept him from doing his feats.

There would’ve been some kind of shit stirring regardless?

Yes, exactly [chuckles]. A shit stirrer.

You’re so lucky he is no longer with us, in a way, if you’re going to make comments like that probably.

Yes.

You pored through a mass of archival footage to assemble the documentary. What was some of the most interesting stuff that you came across?

We had so many gems, and we had a lot from ABC’s Wide World of Sports, which is the most known footage. It was by far the biggest line item in our budget, because we needed to have that stuff in the film. But then we uncovered so many gems. We had a great archival researcher on board.

Things like Evel Knievel assaulting that cameraman at Snake River – we heard the story, we knew about the story, and then lo and behold we tracked down the cameraman, who told us the story, and then almost from out of nowhere we heard that the footage may exist on some news photographer’s reel, who was in New Mexico, I think. That’s just a good example of the kind of discoveries we made. This was really almost an investigation.

Furthermore, we also had people sending us footage, which has never happened to me on a film before. But people caught wind of us doing a Knievel film and sent us footage. We got some never before seen Super 8 footage at Snake River because people heard about it and sent us their footage, which is crazy.

I guess that’s one of the things that makes us different from making a documentary about an unsung hero, where there’s reels lying in storage units. No one’s forgotten that they’ve got good footage of Evel Knievel once they’ve shot it.

Exactly, no. If you have a scrap of Evel Knievel footage in your attic, you’re probably going to remember and you’re probably going to tell your grandkids.

Were there any other major differences between working on a project with someone that had such a huge public personality, and other films that you’ve made in the past?

I think it’s hard, especially with such a seminal figure from my childhood. It’s hard to be completely honest when you’re dealing with such a larger than life character who meant so much to our country, and especially to my generation. It’s a little easier to be objective about an unknown figure. I think that’s not only because you’re being careful about the man’s legacy, or the person’s legacy, but I think you’re also being careful with your own precious picture of the man in your mind, in your 11-year-old mind which still is back there somewhere.

When the film started getting really dark, which it did at times, you start wondering, have we gone too dark? Is there some redemption here, and are we still going to be able to pay homage to the man, which we want to do, even though we’ve gone so dark. That was definitely a big conversation as we made the film, especially in post-production.

Absolutely. I suppose having so much of that stuff on public record, it’s not like you’re uncovering the secrets of Evel – it’s all very well documented. But yeah, you don’t want to end on an utter bummer note that punctures everyone’s childhood hero.

Yeah. It’s like if it’s veering towards character assassination, you’re not doing anyone any favours. Then, by the same token, if it’s just hagiography then why would people bother watching as well? So hopefully the fact that it was at Sundance, and it’s been really well received, is indicative of the fact that we gave a complex portrait of a very complex figure, in a complex time.

What would someone have to do today to make the same impact as Knievel? You include all that footage of extreme sports, and sure, they’re well sponsored, they earn lots of money and lots of people watch them, but it is very much still kind of a niche pursuit, right?

I don’t think that it would be possible to have that kind of exposure today in any genre of entertainment, because there are only four channels on television, and because if you reach stardom at that point, you could reach super stardom. If you turn on your television right now, I guarantee somewhere on some channel there will be somebody doing something a lot crazier than what Evel Knievel did, a much more spectacular thing, and yet it doesn’t generate the same interest because of the media landscape, and also because he was the first of his kind. He arguably invented this genre of sports.