Interview: Denny Tedesco, Director of ‘The Wrecking Crew’

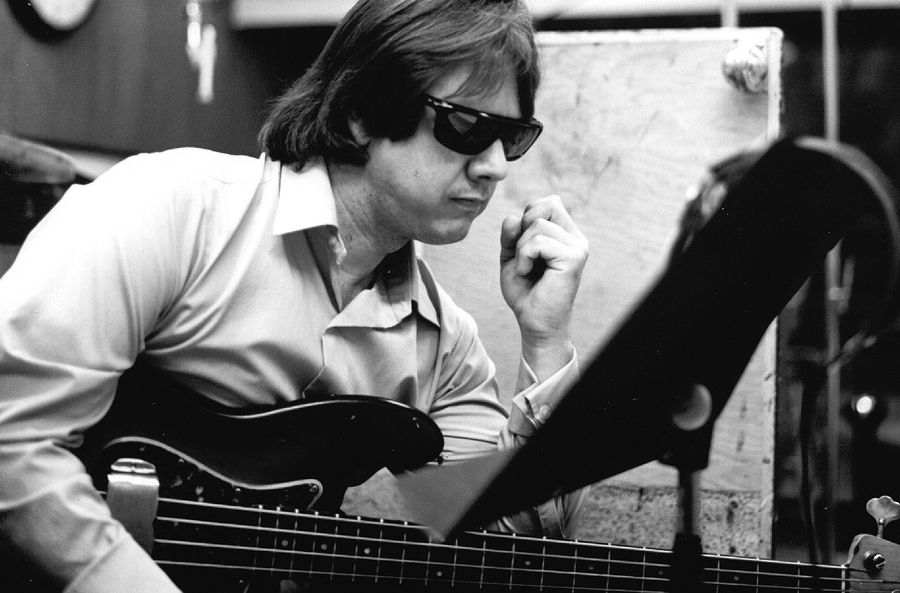

Danny Tedesco’s Dad was a member of the crack team of session musicians who played on everything from”California Dreamin’” to “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’”, “Be My Baby”, “The Beat Goes On”, and “Good Vibrations”. If you saw the Brian Wilson biopic Love & Mercy you saw them depicted making Pet Sounds, now with […]

Danny Tedesco’s Dad was a member of the crack team of session musicians who played on everything from”California Dreamin'” to “These Boots Are Made for Walkin'”, “Be My Baby”, “The Beat Goes On”, and “Good Vibrations”. If you saw the Brian Wilson biopic Love & Mercy you saw them depicted making Pet Sounds, now with Tedesco’s documentary The Wrecking Crew you can get to know the actual people who play on hundreds upon hundreds of the biggest songs in history. We had a natter with Tedesco about his film…

FLICKS: It must feel like forever since you’ve been taking this film out and talking to people about it.

DANNY TEDESCO: You know, it’s funny because yes, the premiere for us here was in March. But, I’ve been showing this film since 2008. People say, “Are you tired of showing it?” I say, “No, because I’m watching audiences now.” I love watching it with an audience because it’s a different thing. Because they laugh at certain points, and there’s points that I didn’t even know were funny parts until you see it with an audience.

I started shooting in 1996.

Wow.

And it wasn’t like, “Oh, I just shot a little.” I was shooting, and I started and dad was diagnosed with cancer, terminal cancer. And I was like, “Okay, we’d better start filming.” And I wanted to tell the story about my dad and about these guys and we started filming, and dad passed away in ’97. We kept going. We had a nice 14 minute tape on VHS, trying to get people interested, and they kept saying, “You’re never going to get this made. It’s going to cost way too much. It’s a music doc.” And I just kept going and, finally, in 2006, my wife was concerned we’d just made a huge mistake. We’d made the biggest home movie ever, and we had nothing to show for it.

The only way to correct that was to make the film. So we borrowed more money and made the film in 2008, 2008-2010 we showed at festivals, no one picked us up. We sold out every session, all the time. We had awards all the time. But it was the reality of the business. It’s a music doc, it’s not going to make money. And the only way to do that is to finish paying this off was to do donations from 2010 to now. I would have sneak screenings. I would do it in theatres, I would rent a place. We’d do it in churches, synagogues, studios, record shops, music stores, homes. Anywhere I could possibly raise some money and show it, I would do it.

I had no choice, and that was the thing. People think, “He’s amazing.” No, here’s the thing is what do I do in 2010? Do I give up? We know the film’s good because we won all those awards. We didn’t have a problem with the film, and audiences loved it. The music was what it is. People love that music. And once they see it they go, “Oh yeah,” and then they get it, and these guys are amazing. As a film maker I think I did a good job, but as an overall story these guys are amazing. That’s what it’s about, and I’m just thrilled that they reacted to it.

I can’t help but think that that crossroads that you found yourself at, where you needed all that extra budget to complete the film, and you thought it was all maybe going a bit south, was a bit like the section of the film where there’s musicians talking about that happening to their careers as well.

There’s so many things in the film that came to me later. You’re right, you’re so on. Exactly. There’s the thing where I say to Plas Johnson, “How did it affect your personal life, being in the studio all the time?” He paused and said, “Let’s just say that I’m a better grandfather than I am a father.” Well, I realised it took its toll on my family here. My kids, they only know daddy does Wrecking Crew. They’re so over it. My kids, the oldest is 16. I’ve been on this for 19 years.

I realised I was focused maybe too much on just getting this thing out, but it was like, “Well, this is my job. I got to get this done or we’ll never recover.” And that was what it was. And I’m glad it went the way it did, and I hope it continues to go that way, that direction.

We all have moments where we feel like we’re emulating one or both of our parents, and I guess it’s happened to you a bit with the picture.

You’re right on, you’ve nailed it. The thing is, my dad, I know what it took for him to be a musician. I didn’t see it because it because he did it before I was born, I’m born in ’61. But I watched him in those seminars and he would tell those kids what it took. He said, “I was 23. I was okay. I was okay because I would practice every day.” He said, “I would do seven, eight hours. I would just turn that music upside down and read it backwards because I didn’t want to memorise it.” He would work at it. I didn’t want to quit, because I’d quit everything else. I don’t play an instrument. I wanted to be a writer, a screenplay writer. I wrote a few scripts but never continued. So, when there’s so many things in your life that you quit, I thought, “I can’t quit on this.” You know what I mean? And I think that was also the determination for me to finish it. I didn’t want to quit.

Did the folks in the Wrecking Crew remain a part of your dad’s life?

No, dad kept them separate. Dad kept music and family life separate, because dad was in the studios 12-14 hours a day, and then he had his own fun time. He was a gambler. He’d be playing cards or golf or whatever. So, when he was home, he was home. It was interesting, because I never saw my dad play music at home and never saw my dad pick up a guitar at home until the mid ’70s, because he was playing all the time. And the only reason he picked it up in the mid ’70s at home was he was doing his own rock and roll– his own jazz albums. So now he’s playing, and doing the clubs, and rehearsing and stuff. First time I saw my dad play guitar at home, and at that point I’m 15, 16 years old. It’s weird to think about it but it’s not like I remember… we didn’t have a hootenanny at home.

What was it like tracking the Wrecking Crew down?

That was amazing because, again, all I knew were names. All these guys, and all I knew was names. I’d met Hal a few times, but Snuff Garrett was the one I knew the most because he was a gambler with dad, and they were heavy gamblers, and they had card games at home. But, other than that it was you’d meet these guys and it was like, “Oh my God.” And they were so receptive to me because they loved my dad. They loved each other. They really were good friends, many of these guys, and they had such respect for each other. And I’m also asking questions that they’ve never been asked. No one cared before. Even the artist. When I talked to Glenn Campbell in 2002, whenever it was, before he really was into Alzheimer’s problems, he’s being asked questions that no one’s every asked him because no one even thought of him as a session player. He’s being asked some stuff, and he loved it. Same thing with all these musicians. And the thing is, I think that’s why they trusted me. Because I’m asking questions like the fact that, “Hey, Plas, how did it affect your personal life, not being there? I know how it affected mine.”

There are non-musical questions, because I want everybody to relate to that. So anybody that hears that question, you could be a carpenter, you could be a postman, you could be anything. We’re all trying to make a living. Especially freelance, as a writer. How do you do that? How do you balance that? The other one was Bones Howe. When you’re at the top of the world and then you’re not at the top — what happens? When Bones said you get the ramp up and you’re at the top of the world, you’re at the top of the ramp, and it was that line “taking the ramp down is what it’s about, not staying at the top”. And now I realise that word is relevance. We want to be relevant in our lives, no matter where you’re at in your life.

You could basically apply that to any creative type.

It’s funny, because I don’t know where I’m at. The thing about being creative – all of us – as writers, or singers, whatever it is, doesn’t matter. We still answer the phone thinking, “This could be it.” Unless you’re a sports person, you’re a football player a boxer, well you know you’re not going to box anymore, hopefully. Or you know you’ve retired, physically can’t do it. But you just feel like you’ve got one more in you. Like John Travolta was washed-up, and then Pulp Fiction comes around, and he’s up again. You can always have that as an actor.

Thank goodness for the Church of Scientology, eh?

[laughter] Maybe that’s my problem.

Which parts of conversations surprised you when you were talking to these folks that spent so much time with your dad?

You know what, they all got along. You know, when there’s a jerk in the crowd, they all talked about the jerk. Jerks are consistent. But most of all, they all pretty much got along well. They had to, or you don’t get hired. If you can’t play with the boys, you can’t play. You could be the greatest player in the world but, if you’re a total jerk, no one wants you in that studio. I’m always blown away that they had no idea what they were doing, I mean creating. It makes sense, though, because they’re not creating hits. They were recording songs that become hits. Up Up and Away is the perfect example. My father had no idea he was on that, and the only reason he knew that was when Jimmy Webb gave him a Grammy charm when he won the Grammy. It was a little charm bracelet. And he said, “What’s this for?” He says, “It was that thing we did with Fifth Dimension last year. It was record of the year.” “Oh, all right, cool.” And I’m going, “How do you not know that?” Because he’s not listening to radio, my dad.

Right, okay.

If you hear Up Up and Away, and you saw the film, you know his Spanish style guitar. You hear it, the fills, you hear it all over the place. Especially in the Fifth Dimension stuff. But he’s not listening to music. He’s working 12-14 hours a day. These guys are playing music, and never the same music. Occasionally, they’ll play this maybe another re-record of something else from a different group but it’s all new to them. So it’s a factory.

I get it. It’s like if you spend your day working hard on something, you don’t do it when you get home.

No. I don’t ever remember my dad listening to music, ever, until later, maybe ’70s or ’80s. I never saw him listen to music. It was sports. It was TV. It was gambling. That was his thing. And my brother, thank God my brother was ten years older than me. At least I had an outlet. Or something coming in that influenced me music-wise, not knowing my dad was on some of those albums that my brother’s playing. My dad didn’t know he was on those albums. Sometimes you knew who it was, and sometimes you didn’t. They knew when they were playing with the Beach Boys, probably, because Brian was there, and Brian was special in the end. They knew he was different.

You’ve got your fireman’s hat on. There’s a couple of dogs coming through. There’s all that stuff happening.

Exactly.

That’s a different day at the office.

You know, it’s funny because there was a lot of stuff he wasn’t on with the Beach Boys. It was a drag. It’s like, “Oh God.” He’s on Pet Sounds but he was on the actual song Pet Sounds which wasn’t that great. It’s like, “Come on, dad.”

Took the wrong gig that day?

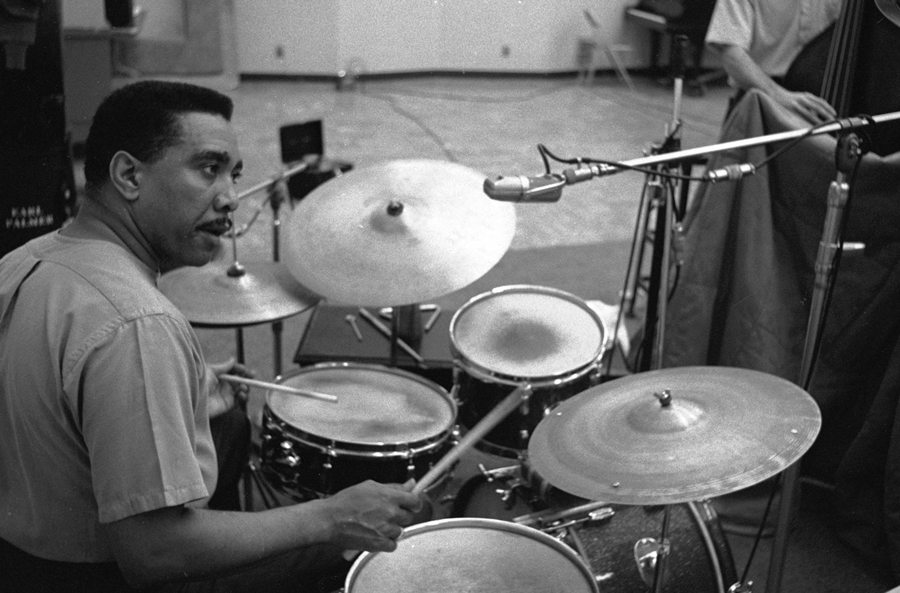

Yeah, exactly. Who knows what he was doing that day? A guy at the union, talking about 1967, said, “Man, there were three people that were working all the time, that had the most. There was Earl Palmer, Hal Blaine, and your dad.” They had 400-something contracts within the union. So you got to figure you had Christmas off, right? And you had a vacation somewhere, maybe, at the weekends, and you probably had some cash dates or casuals or something that you didn’t do. That wasn’t reported. So he could do three or four dates a day. Every day, someone’s throwing you something different. It could be jazz, it could be some country stuff, cartoon music, film music, commercials. Everything. So it was a special time for him.

You must have had a ridiculous amount of footage to put together, and it must have been very difficult to decide what would make the cut.

When I gave it to the editor, she said, “You’ve got to stop interviewing people because I can’t put everybody in this.” And I said, “Well, that’s why God gave us DVDs.” And she was right. She said, “You can’t put five seconds, ten seconds of each person telling a story, whatever. You’ll never fall in love with people.” I said, “I totally get it,” but I kept interviewing people because I didn’t know if there was going to be one of those oh my God comments, or I just wanted them because they were young and alive. 10, 15 years ago, when you’re doing an interview at 65 or versus 85, it’s a big difference, as you know.

I was able to go back and include more on the DVD and Blu-ray. Thank God Magnolia let us do it. Because they said, “No, we’re just one disc and a few extras.” I said, “No. Do not do that to me.” I said, “This is way too important. Historically, it’s way too important.” So on the DVD bonus material I’ve got Bill Medley, Petula Clark, Jackie DeShannon, Barry McGuire, Richard Carpenter, James Burton, and so many other musicians and engineers. And I did outtakes of the best of the engineers. Best of the writers and producers. And I could have kept going. So when we cut it, I needed a beginning, a middle, and an end. But, when we had a two-and-a-half hour, two-hour-and-forty-five-minute cut, the only way to cut it down was, “If it’s not relating directly back to the musician, it comes out.” That’s why, when we talk about Beatlemania, how did the Beatles affect the business here? How did radio affect the business? What is the red light syndrome, why some guys can make it and some guys can’t? You know what? It was all great stuff, but it didn’t matter. We had to take it out.