Why ‘Finding Nemo’ is the Greatest Pixar Film Ever

Ever since Pixar made a lamp move, the studio has been known as an innovative CGI animation juggernaut. Three decades later, with 17 feature films under their belt and too many Oscars to count, the world has come to recognise them first and foremost as cinematic storytelling wizards who cater to every age. Like a […]

Ever since Pixar made a lamp move, the studio has been known as an innovative CGI animation juggernaut. Three decades later, with 17 feature films under their belt and too many Oscars to count, the world has come to recognise them first and foremost as cinematic storytelling wizards who cater to every age.

Like a bear hug that wraps around the Earth, the warmth in Pixar’s stories are large and far-reaching. Everyone has an undisputed personal favourite Pixar pic that they feel attached to, and that no one can take away from you. So when someone tries convincing you that one particular Pixar film is ‘The Greatest’, it’s pretty much impossible if you already think otherwise.

And yet, here I am, attempting the impossible by stating that Finding Nemo is the greatest Pixar film ever made. With Finding Dory currently in cinemas, I feel pumped to say this now more than ever.

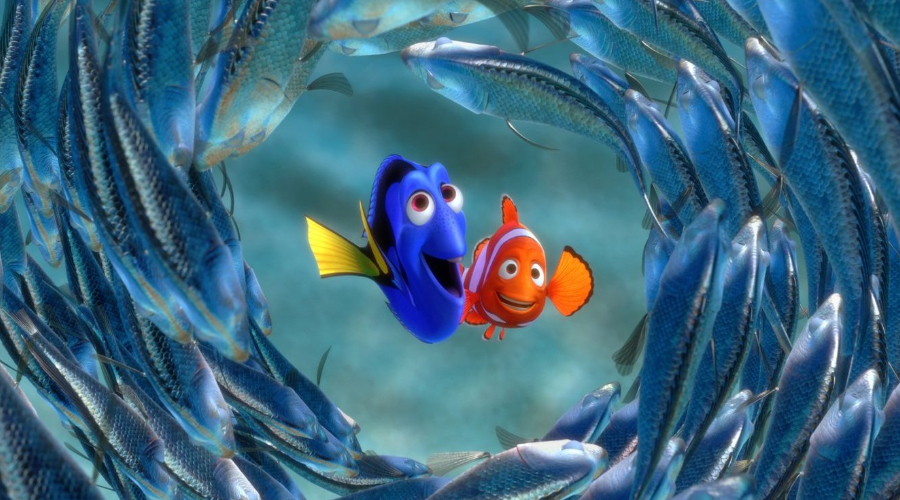

Released in 2003, Finding Nemo is Pixar’s fifth feature about a clown fish whose one and only son, Nemo, gets taken away by a diver. With the help of a blue tang named Dory, who has short term memory loss and a heart of gold, they journey across the ocean to get Nemo back. (I’m fairly certain you know all this.)

The film was the second-highest grossing film in the US Box Office that year, toppled only by the final chapter in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Critics went crazy for it, which led to Nemo being the first Pixar film to win Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards (that category only started in 2002).

The studio had a rock-solid reputation before then, wowing audiences with two Toy Story films and not-quite-wowing-but-still-OKing them with A Bug’s Life. They were all premium-looking films of their time, even if their age shows today.

Toy Story

Toy Story 2

A Bug’s Life

But hey, age does that to all good things.

Nemo was also coming off the back of 2001’s Monsters, Inc., a film that woo-ed on a technical level with complex rendering of clothing and – more importantly – Sully’s hair. It was a big deal back then.

The physics of the fur and fabric were impressive, for sure, but are mere staircases compared to the mountain of visual complexity needed for Finding Nemo’s greatest technical asset: water.

If you think replicating the movement of a puddle is difficult, try adding the entire ocean to the mix. Waves ripple, increase, decrease, calm and ripple again in a multitude of unpredictable patters that are dependent on what creatures and things are inside them. Once Pixar got that down, the studio then had to think about how light moved and interacted with the the characters, the textures, and the density of the liquid.

That’s the simplified version of the God-like calculations involved in making water work in the film. Rendering a single frame (roughly 0.04 seconds) sometimes took up to four days because of all the computing power needed. But it was all worth it to achieve a dynamic look that still holds up today.

On a purely technical level, Finding Nemo was Pixar’s ascension into another visual realm. This would be followed by the likes (and glorious looks) of The Incredibles, Cars and Wall-E. If you were to mark a point in time where technology caught up with Pixar’s own creative vision, it would be on Nemo.

But the aesthetic of Finding Nemo isn’t its championing feature – it’s the characters and the story.

Dory is the instant favourite among kids, as with all comedic sidekicks, and Ellen DeGeneres fits her voice so well that it’s impossible to imagine anyone else in the role. The bountiful side characters yield their own moments of comedic gold, from the Aussie shark trio holding their own AA meetings to the aquarium fish who put a new spin on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Yet, the real anchor of this film is Albert Brooks’ exceptional vocal performance as Nemo’s dad Marlin. His dry comedic deliveries are the perfect contrast to DeGeneres’ off-the-wall pitches, but it’s his ability to communicate heartbreak from a wail to a whimper that really sells the character. Marlin goes from awkward to anguish so many times throughout the film that a lesser actor would have slipped on one of those vocal extremes, but Brooks handles those traits like a master.

We immediately understand why Marlin is so overprotective of Nemo with a sequence that ranks as Pixar’s most tragic opening scene. You might want to object and give that title to Up, but while that scene is indeed tearjerkingly magnificent, don’t forget that Carl and Ellie still lived a full life together. Marlin was given no such luck with his family.

Everything that makes Finding Nemo great can be found in this opening. As limited as her screen time is, we get an immediate impression of Nemo’s mother and how much she and Marlin loved each other with a simple, playful interaction. In a way, the animators make the pair dance.

Then, the ultimate tragedy unfolds. Marlin wakes up to find his partner and his eggs gone. In one perfectly framed shot, we see Marlin alone in the vastness of the ocean with only a few streaks of lights illuminating him and his empty home.

It’s dark. It’s painful. It seems hopeless. But then he finds one surviving egg, and suddenly all the sorrow is extinguished with a single promise: “I will never let anything happen to you, Nemo.”

On a technical level, an artistic level, and a storytelling level, Finding Nemo is Pixar at full capacity. It capitalised on the studio’s previous experiences and acted as a precursor for their Golden Era (Wall-E, Up, Toy Story 3). No film has been more essential to their pristine reputation, and that’s what makes Finding Nemo the greatest Pixar film ever made.

Finding Dory is now playing in cinemas, find times/book tickets for 2D and 3D.