Seen That? Watch This: Thirteen Lives and Ron Howard’s other near-disaster movie

The director achieved a stronger sense of exhilaration in his outer space survival drama Apollo 13.

Seen That? Watch This is a weekly column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release—here, Thirteen Lives—and matching it to comparable, superior works. This week he recommends returning to Ron Howard’s other near-disaster movie: Apollo 13.

Ron Howard brings the Ron Howard touch to the story of the Tham Luang cave rescue—except he kind of doesn’t. Gone are many elements synonymous with the veteran director’s work: narrative briskness, for instance; a clean and polished visual style; a rousing score; and screenwriting contrived in that quintessentially Hollywood way, with characters delivering lines like “failure is not an option!” at the opportune moment.

It becomes clear early in Thirteen Lives that Howard is going for level-headed, strait-laced, sober-minded recreation, prioritizing realism and story details, and pre-empting potentially problematic aspects. Issues that didn’t have cultural currency in his prime—such as the white saviour trope—are handled sensitively.

This may be noble-minded, but something has been lost in the director’s new-found sensibility. His style, for starters, which is now anonymous: take Howard’s name off the credits and you’d never know Thirteen Lives was one of his movies. Despite an inspirational storyline, the process-driven narrative doesn’t feel humane or especially empathetic. The thirteen lives mentioned in the title don’t refer to people—a dozen young soccer players and their coach—who we come to know, least of all understand, given very little time is spent in their company (which was also the case in another, so-so film made about the rescue: The Cave).

Those titular words describe not a group of people, but a problem.

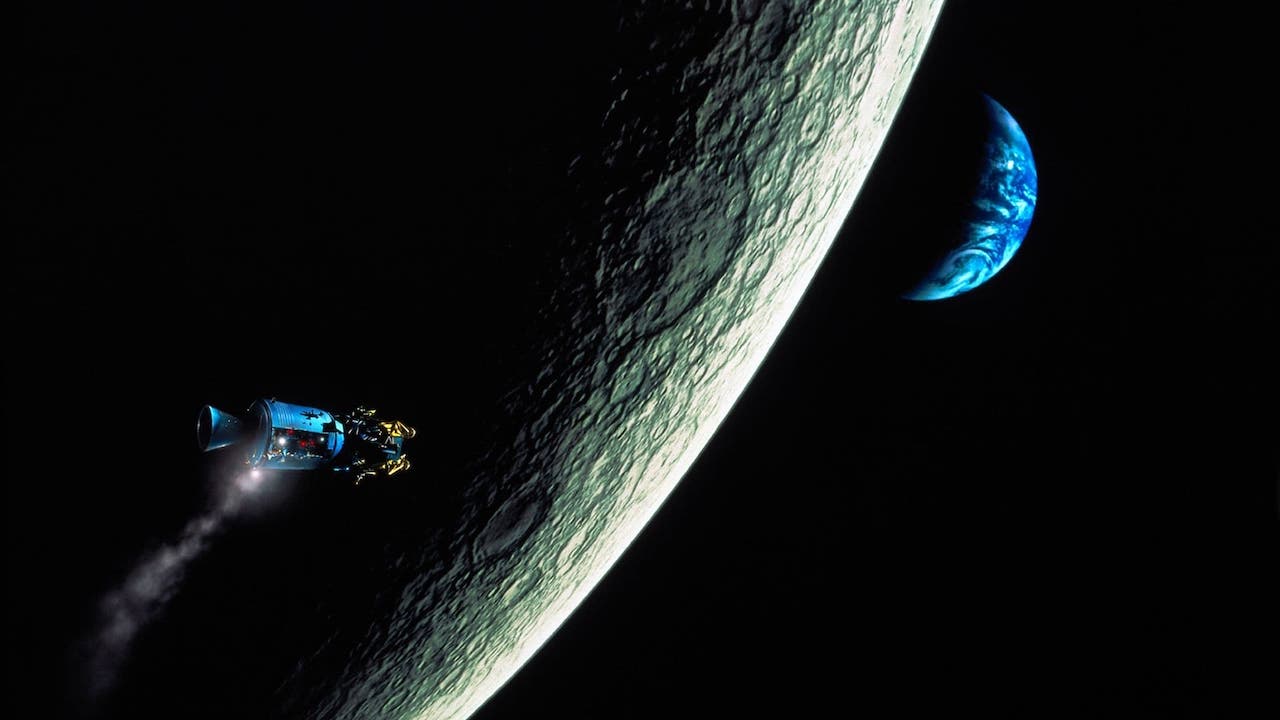

It’s not the first time Howard has helmed a near-disaster movie with a well-known happy ending. Apollo 13 is his other, more famous, and much more entertaining film about real-life people rescued from perilous circumstances through perseverance and outside-the-box thinking. In the 1995 classic Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton and Kevin Bacon play astronauts piloting the ill-fated titular rocket ship, which was supposed to journey to the moon but arrived at the edge of oblivion, after damaged writing sparked an explosion that leaked oxygen into space. Oxygen being that cherished element among human beings, rather helpful for that activity we call breathing, and in this instance also needed to generate power on the ship.

This dramatic event occurs around 50 minutes in, marked by the flashing of various red lights and Bacon commenting “hey, we’ve got a problem here.” At that point Hanks takes over, not to pilot the ship to safety but for something far more important: delivering the line that made the trailer and became iconic—“Houston, we have a problem.” At the one hour mark the intensity ratchets up and the film really hits its stride.

Howard finds a good rhythm by oscillating between two core locations: the tin can with Hanks’ Jim Lovell and co far above the world, floating in a most peculiar way, and NASA ground control where men in suits and ties sweat, smoke, and brainstorm ways to get the astronauts home.

Pace-wise Thirteen Lives (a far slower film) also picks up around the one hour mark. The beginning of its most interesting section occurs when diver Rick Stanton (Viggo Mortensen) comes up with a “crazy idea” to save the boys by injecting them with ketamine, then ferrying their unconscious bodies out of the cave like parcels (yes, this really happened). When he explains the idea to Harry Harris (Joel Edgerton), the fellow diver and anaesthetist responds in a way that sharpens our interest, shooting back: “It’s insane, it’s unethical, it’s illegal.” And god damn, it worked.

While the film takes a long time to reach this high point before it fizzes out fairly quickly, Apollo 13 is paced well from the start. Howard’s new-found devotion to realism not only saps Thirteen Lives of energy but reduces its emotional impact by taking us outside the characters’ heads and keeping a cold, careful distance.

Two dream sequences in Apollo 13 reveal what Howard would never do in Thirteen Lives. In the first, pre-launch, Lovell’s wife Marilyn (Kathleen Quinlan) has a nightmare in which the mission goes disastrously. In the second, after it’s clear the ship will not be completing its mission, Lovell stares out its window and we witness a fantasy inside his head—of him landing on the moon and running his fingers through moon dirt. The earth is in the background, triumphant music blaring.

This scene isn’t as cheesy as it reads. It’s obvious, but it also uses visual language (you could turn the sound off and it would make perfect sense) to express the character’s thoughts, merging the outer with the inner. In Thirteen Lives, everything is outer: the narrative, camera, direction occupying a detached distance. If Howard is thinking about his approach more, he’s feeling it less.

Instead of venturing into the cave, perhaps it’s time to return to space.