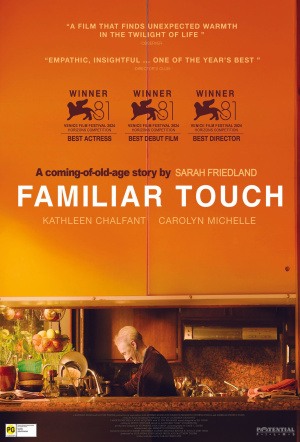

Familiar Touch tenderly shows a side of dementia rarely explored in film

Tranquil direction and one exceptional performance drive the compelling thesis of this film: that dementia and dignity can co-exist.

The opening ten minutes of writer-director Sarah Friedland’s Familiar Touch lets you know exactly what you’re getting into. We’re introduced to Kathleen Chalfant’s Ruth, an elderly woman living what looks to be a serene and solitary life, as she meticulously prepares a delicious-looking meal for herself and a middle-aged man named Steve (H. Jon Benjamin). Everything’s patiently paced, devoid of a score letting you know how you’re supposed to feel. It all seems quite normal, even her innocent flirting with this Steve guy who she—or we—knows very little about. Until she touches his thigh, causing him to jerk backwards in a way that lets the observant know exactly who he is.

This is the point Friedland demands the audience lean in for the next 80 minutes, fully trusting her performers to communicate what’s really going on without directly stating it. This is also the point where Ruth’s tricked into entering a vehicle ready to take her to an assisted living home.

Films have a tendency to dwell at either ends of the dementia spectrum, whether it’s the heartache of early diagnosis (see Harry Macqueen’s Supernova) or the horror of late-stage dementia (a la Florian Zeller’s The Father). Some films, like Michael Haneke’s Amour, run the full gamut. But very few float along the in-between spaces like Friedland’s Familiar Touch.

The Father

Amour

Ruth often isn’t lost. She’s perceptive, jovial, independent, and filled with desires, making her relatable in a way that dementia-riddled characters so often aren’t in films. Her moxie, combined with her sense of awareness, flourishes in a scene that sees her recite a detailed borscht recipe to her doctor Brian (Andy McQueen) in an effort to prove soundness of mind.

Sadly, the dementia emerges just enough to warrant her need for assistance. But Friedland refuses to let the story wallow in misery, keeping tight hold of her tranquil direction. This, combined with Chalfant’s incredibly tuned performance, help sell the film’s quietly profound thesis: that dementia and dignity can co-exist.

As with mental health in general, community and environment play a significant role in Ruth’s new life. The staff, especially, show the kind of patience and understanding that we could all benefit from adopting. Carolyn Michelle, in particular, radiates as Vanessa, a nurse with considered gentleness that doesn’t topple over to condescension. It’s not just that she respects the residents; Vanessa also has a good read on them, nimbly talking through dementia episodes one moment and frankly stating when a line’s crossed the next.

Being able to live in a pretty flash assisted living home also helps, and Friedland’s aware of that privilege. In a fairly simple scene, Ruth spies Brian and Vanessa on break talking about how their own folks couldn’t afford to live in a “geriatric country club” like the one that employs them. It’s a subtle bit of self-awareness but don’t expect Familiar Touch to jump on a soapbox and monologue about health discrepancy between the haves and the have-nots. It simply isn’t that kind of film.

Friedland opts instead to show what a dignified life with dementia looks like in a place that can provide it. The director’s firm understanding of the subject is unquestionable, boosted by the fact she shot the feature at Villa Gardens—an actual continuing care retirement community in Pasadena, California—with a production crew that included residents and staff.

But everything ultimately circles back to Chalfant’s exceptional ability to let liveliness, humour, wisdom, and earnestness define her character—not the dementia.