Jason Statham is a busy bee in the so-bad-it’s good The Beekeeper

This action-revenge bee movie—sorry, B-Movie— is almost breathtakingly funny, even if comedy gold isn’t its intention.

Luke Buckmaster couldn’t help but laugh out loud at David Ayers’ The Beekeeper, an action-revenge movie positively riddled with cliches and bee-centric metaphors. Sounds like a buzzing good time.

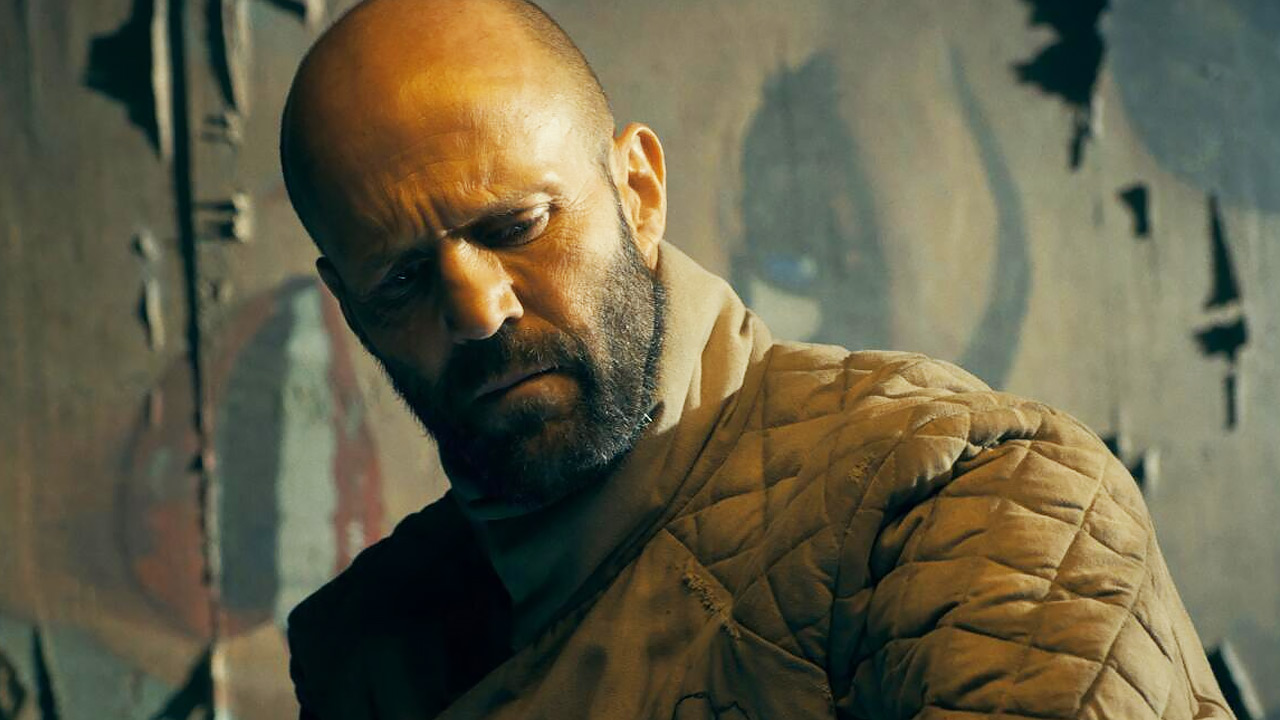

“To be or not to be” is literally the question in Jason Statham’s latest explode-a-palooza, a sensationally silly yet resolutely staight-faced revenge movie—almost certainly action cinema’s most bee-centric production. Statham’s protagonist Adam Clay, aka “The Beekeeper,” is asked that question by a buff goon who believes he’s delivering a clever line before sending Clay to the great beyond. There were no subtitles in the cinema, of course, so I can’t be certain if I spelt the quote accurately. This character might’ve been repackaging Shakespeare for the insect realm: “to bee or not to bee?” Or contemplating inter-species existentialism: “to be or not to bee?”

Perhaps I’ll never know. I am sure, however, that this is the kind of B̶ ̶m̶o̶v̶i̶e̶ bee movie for which the terms “guilty pleasure” and “so bad it’s good” were coined. I found The Beekeeper almost breathtakingly funny, laughing out loud heartily at least a dozen times, even if comedy gold wasn’t director David Ayer’s intention. One could endlessly poke holes at it, beginning with its Frankensteinian unoriginality, every limb sewn together from umpteen other films. Then there’s its outrageous over-egging of bee-related metaphors, reiterated again and again through dialogue such as “sometimes when the hive is out of balance, you have to replace the queen” and “I’m a beekeeper, I protect the hive.”

There’s also Statham’s impenetrably humourless and hardened performance; he’s more of a talking two-by-four than a man. And of course there’s the plot: a familiar revenge narrative hinged on a dormant menace—Statham’s Mr. Clay, of course—reawakened by a moral imperative. Here it’s to exact revenge on a bunch of tele-scammers, who rip off the kindly Eloise (Phylicia Rashad), the only person who ever took care of him. They pay for it big time, which let’s face it is an appealing fantasy; it made me wonder why telemarketers receiving grisly comeuppance isn’t a more common occurrence in popular culture.

The moment after Eloise’s bank accounts get drained, Ayer cuts to Clay taking honey from bees: one of his first—but far from last—heavy-handed connections. Eloise’s daughter Verona (Emmy Raver-Lampman) is an FBI agent, but avenging mum ain’t a job for the usual authorities, with their laws and protocols and lack of insect-related methodologies. Surrounded by the infallible force field of the Hollywood action hero, Clay arrives at a call centre with a couple of jerry cans of petrol, announcing he’ll burn the place down, and staying true to his word. The angel of death protagonist follows the money all the way to the top: to the rich and fiendish Derek Danforth, a 28-year-old coke-snorting swindler played with very convincing brattishness by Josh Hutcherson.

One of Danforth’s colleagues is the wise but crooked Wallace Westwyld (Jeremony Irons), who immediately understands the scale of the threat. When Danforth asks “how have I fucked up?”, Westwyld responds without hesitation: “you disturbed a beekeeper.” Irons, the film’s most impressive and perhaps only thespian, must have had a good time with the material, which even indulges him with a monologue unpacking the ancient relevance of the beehive and how it informed a team of secret operatives who, “not unlike bees, keep working until they die.” An insane twist involving the identity of the queen bee (this makes more sense in context) sets the scene for a preposterous stakes-upping finale.

Ayer understands a grindhouse-y movie like this can be terribly unoriginal and onerously unsubtle, but it should never be boring—so he keeps it pacey and pressure-packed. There’s no overt wink-winking the audience: Ayer in fact is so serious about the whole bee thing he even coats many scenes in honeyed colour grading, our insect friends infecting the film’s form and essence.

The Shakespearan quote mentioned at the beginning of this review, by the way, does not belong to a lengthy soliloquy, like Prince Hamlet’s. It’s a one-liner that generates another one-liner from Clay. Before spectacularly defeating the goon with a gun to his head, the hero says: “I think I’ll choose to be.” But might he have meant “I think I’ll choose to bee“? Again, we’ll never know.