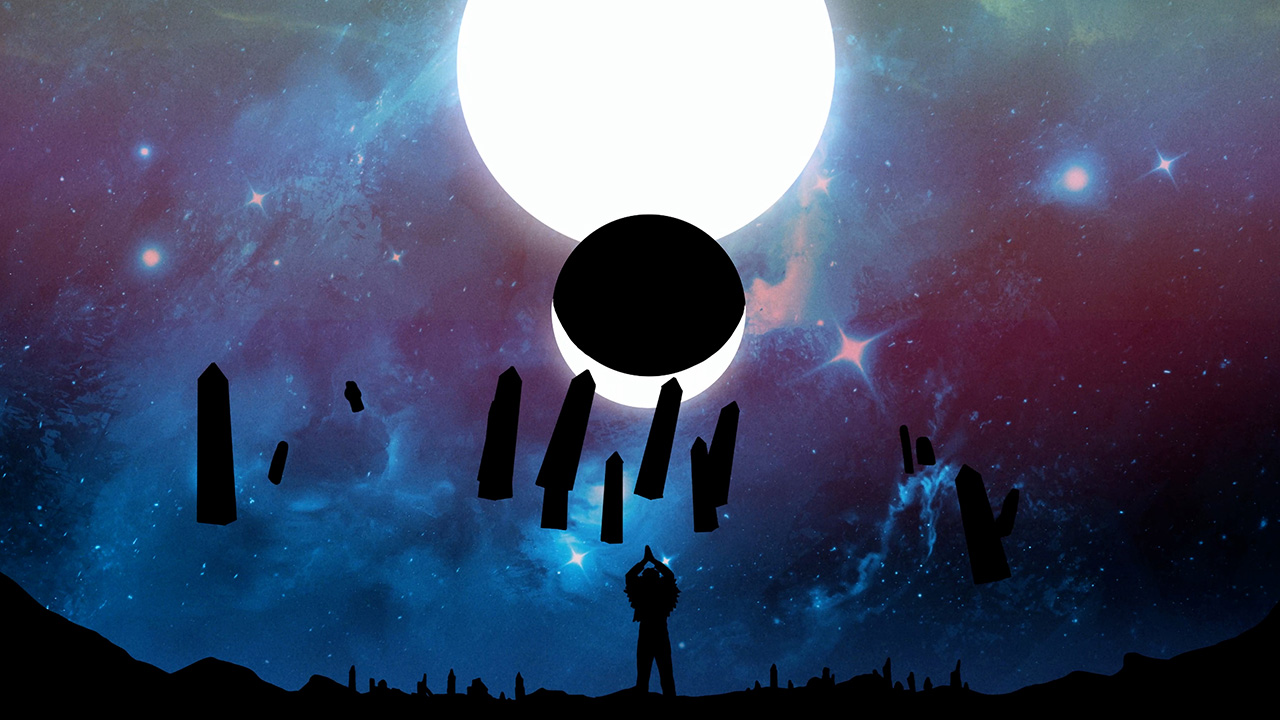

Violent fantasy epic The Spine of Night is a rare, otherworldly animated experience

This feels destined to be cherished by a cult audience.

Lucy Lawless and Richard E Grant lend their voices to fantasy anthology flick The Spine of Night. As Liam Maguren writes, it’s a very violent and very naked love letter to an underused form of animation.

Rotoscoping, the technique of tracing live-action subjects frame by frame, has been a part of the animator’s tool kit since the Fleisher Studio days. Filmmakers like Walt Disney and Richard Linklater have lovingly harnessed the effect in cinema but Ralph Bakshi was arguably its biggest pioneer, pushing the niche method far and wide with a bunch of rotoscope fantasy adventures in the ’70s and ’80s like Fire and Ice and his version of The Lord of the Rings.

Visually smashing the imaginary with hyperreality, rotoscope animation nestles these fantasy worlds in a unique uncanny valley far removed from Disney fairy tales of yore or CG-heavy blockbusters of today. With cosmic anthology epic The Spine of Night, directors Philip Gelatt and Morgan Galen King conjure a very violent and very naked love letter to this underused form of filmmaking.

The plot, spanning generations and planes of reality, draws inspiration from Walter M Miller Jr’s A Canticle for Leibowitz. Framed around a mystical blue flower and an encounter between hardened witch Tzor (voiced by Lucy Lawless) and a nameless withered guardian (voiced by Richard E Grant), the pair exchange stories within a dead giant’s skull to explain what they know and where they come from.

As with almost any anthology feature, some stories are more gripping than others. The first tale, which explains Tzor’s place in the world, doesn’t mess around with a ruthless yarn about deforestation and colonisation. A perfectly cast Patton Oswalt provides the weaselly voice of a petty coloniser looking for daddy’s approval. You’ll learn to hate his face and love what the film does to it (if you’re a spiteful sicko like me).

The second tale deals with knowledge inequality within a walled-off township and gets us better acquainted with weedy miscreant Ghal-Sur (Jordan Douglas Smith). He’s an effective bad guy but Inquisitor Uruk might be the film’s most memorable villain, an egotistical librarian wielding page-turning sticks like claws voiced deliciously by Malcolm Mills. When the townspeople revolt, that’s when The Spine of Night really opens the bloodgates.

What the battles in the film lack in kinetic movement, they make up for in gruesome details. A knife to the back looks simple in motion but the sight of the spinal column peaking from the wound adds some tremendous weight to the stab. As does a pole through the skull which, again, looks pretty straightforward until you notice an eyeball dangling on the other side. The unique ickiness of the violence stems from the aforementioned uncanniness of the animation style, something about seeing pseudo-real 2D anatomy torn apart so precisely and unceremoniously really lands. Don’t even get me started on those who melt to death…

Unfortunately, The Spine of Night‘s third tale exposes the film’s biggest weaknesses. Centred on two lovers who catch a glimpse of the blue flower’s magic, this brief story leans heavily on the pair’s conversation about mortality and the cosmos. However, the Diet Shakespeare dialogue combined with weak voice acting causes the scene to buckle under its own weight. Comparing the stars to “sparrows falling into the lake of ice and diamonds” doesn’t sound that profound when performed like a university student who just smoked their first blunt.

Spotty vocal performances can be found throughout The Spine of Night, but fortunately, seasoned pros like Lawless and Grant ground the script with enough gravitas to sustain its admirably succinct 93-minute running time. This is especially true of the fourth story, a fantastical world-building flashback narrated entirely by Grant.

The final story (before the film’s conclusion) is one big action set-piece centred on three soldiers in bird-like attire. It’s quite wild and I feel compelled not to write any more about it.

What I will write, or rewrite, is that this film is very naked and might hold the record for the most boobies and ding-dongs in an animated feature (I haven’t crunched the numbers). While some could argue that all the nudity’s unnecessary, it does help distance The Spine of Night‘s world from our prudish one. Tzor’s naked throughout the entire film, but no one remarks on this or any other clothesless individual. There’s also no sex or sexual violence, classily cementing the normalised nudity (of numerous shapes and sizes) within this universe.

The supernatural atmosphere is carried home by Peter Scartabello’s mind-engulfing musical soundscapes made up of classical instruments, throwback synth, and a spring from a garage door. It couldn’t have been easy to audibly match The Spine of Night‘s surreal visuals, but Scartabello found a way.

Those who embrace The Spine of Night will do so for its bloody and beguiling aesthetics, not for its occasionally wobbly storytelling. That may not be enough for some, but those who look past the unremarkable aspects of the script will be left with plenty to keep them entranced. It’s the kind of otherworldly experience we rarely get to see and feels destined to be cherished by a cult audience.