An island of other realities: the magic of Venice Immersive

Venice Immersive – recently visited by Flicks critic Luke Buckmaster – is part of the Venice Film Festival, devoted to virtual and mixed reality experiences. It showcases art that blurs reality and redefines how stories can be told.

In my writing on virtual reality, I’ve often returned to the idea of arriving—that lovely word evoking the crossing from one place into another. Sometimes we’re welcomed into the sacred (as in the 360 film Collisions); sometimes we pass through a magical threshold (as in Jon Favreau’s Gnomes and Goblins); and sometimes we drift in gently, on a vessel that reveals the world we’re about to inhabit (as in The Walking Dead: Saints and Sinners).

So it felt fitting that my first encounter with Venice Immersive—a haven for virtual and mixed reality enthusiasts, held annually as part of the Venice Film Festival—began not with a headset, but with a voyage: a boat ride to the tiny island of Lazzaretto Vecchio, located just off the Lido. This is where the conventional festival takes place, buzzing with cinephiles, tourists, the press and glitterati. For me, living in Australia, it’s quite literally on the other side of the world.

For most of the year, Lazzaretto Vecchio—which has a peculiar past as a monastery, plague quarantine site, and leper colony—lies more or less dormant. For a few weeks it ignites into a crucible of experimental art, testing the boundaries of new storytelling. This year’s program featured 69 projects from 27 countries, exhibited in minimalist, elegantly designed installation spaces—some small and curtained, others more expansive and elaborate.

Some of the works were nothing short of astonishing. Take the 50 minute experience Blur, which combines live actors and virtual elements, hurling us through a dystopian future where the real and unreal dissolve, engaging every sense except smell and taste (although at one point I nearly drank a mysterious white fluid, until a performer directed me to pour it into an ashtray-like vessel, where it fizzed into a luminous eye-popping red). You can read my full review of this and other Venice Immersive titles on The VR Critic, my website dedicated to VR and MR experiences.

Or consider the 60 minute The Clouds Are Two Thousand Meters Up—perhaps the hottest ticket item on the program, which won Venice Immersive’s top prize. This experience makes good on VR’s promise as a medium that enables us to step into other worlds and lives, marrying deep immersion with an emotionally powerful narrative about a widowed man who learns more about his late wife by entering the world of her unfinished novel. Its impact is hard to capture in words; at one point I feared I would start crying, and my tears would spill and fog the headset, compromising the illusion.

Spend some time at Venice Immersive and a peculiar energy begins to take hold: a sense of standing on the threshold of something, perhaps many things, very special but difficult to define. The ground feels unstable, shifting beneath your feet. That uncertainty—of not knowing exactly where the technology is going—is part of the thrill of participating in a rare historical inflection point, during which a medium hovers between states, not fully born and certainly not ready to die. Cinema, after all, did not arrive fully formed: it took decades of experimentation to develop an accepted grammar and syntax and “go mainstream.”

During my time as a climate activist, I encountered a curious phrase borne from France’s tumultuous 1968 protests: “Be realistic, demand the impossible.” One evening, departing Lazzaretto Vecchio, those words returned to my mind—this time in the context of what Venice Immersive’s co-curators, Michel Reilhac and Liz Rosenthal, have achieved. In their hands, the impossible—or near-impossible—has taken shape. The event is amazing on its own merits, but even more remarkable when viewed against the global backdrop in which it unfolds.

Film festivals across the world are withdrawing from immersive programs, after several years of tentative experimentation. There are various reasons for this, i.e. budgetary issues (many festivals are struggling in general) and the difficulty of scaling extended reality experiences. The Palazzo del Cinema, the main venue of the Venice Film Festival, can seat more than 1000 people, their eyes fixed on a two-dimensional screen, absorbing an experience that’s entirely pre-programmed and non-interactive.

By contrast, The Clouds Are Two Thousand Meters Up can be offered only to a single participant at a time (per room; there were two at Venice Immersive) and runs for one hour. This exclusivity gives it an added aura—a rare, luminous space to step into—but scalability remains a major factor in the ongoing conversation around the medium’s viability and uptake. This is a conversation, perhaps, for another time; for now, what matters is the miracle of this art being available to experience at all.

Below are my thoughts on some productions I experienced at this year’s Venice Immersive, with links to read the full reviews.

The Clouds Are Two Thousand Meters Up

Director Singing Chen’s exquisitely moving experience encapsulates a simple but profound truth: that stories belong to places, and places tell stories. This beautifully crafted production lets us follow Guan, a Taiwanese lawyer on a melancholic mission to understand his recently deceased wife by entering the world of her unfinished novel.

Blur

This hybrid mixed reality and immersive theatre experience is a cautionary tale about the dangers of genetic mutations and the human desire to transcend mortality. Its images are surreal, creepy, and poignant—sometimes all at once.

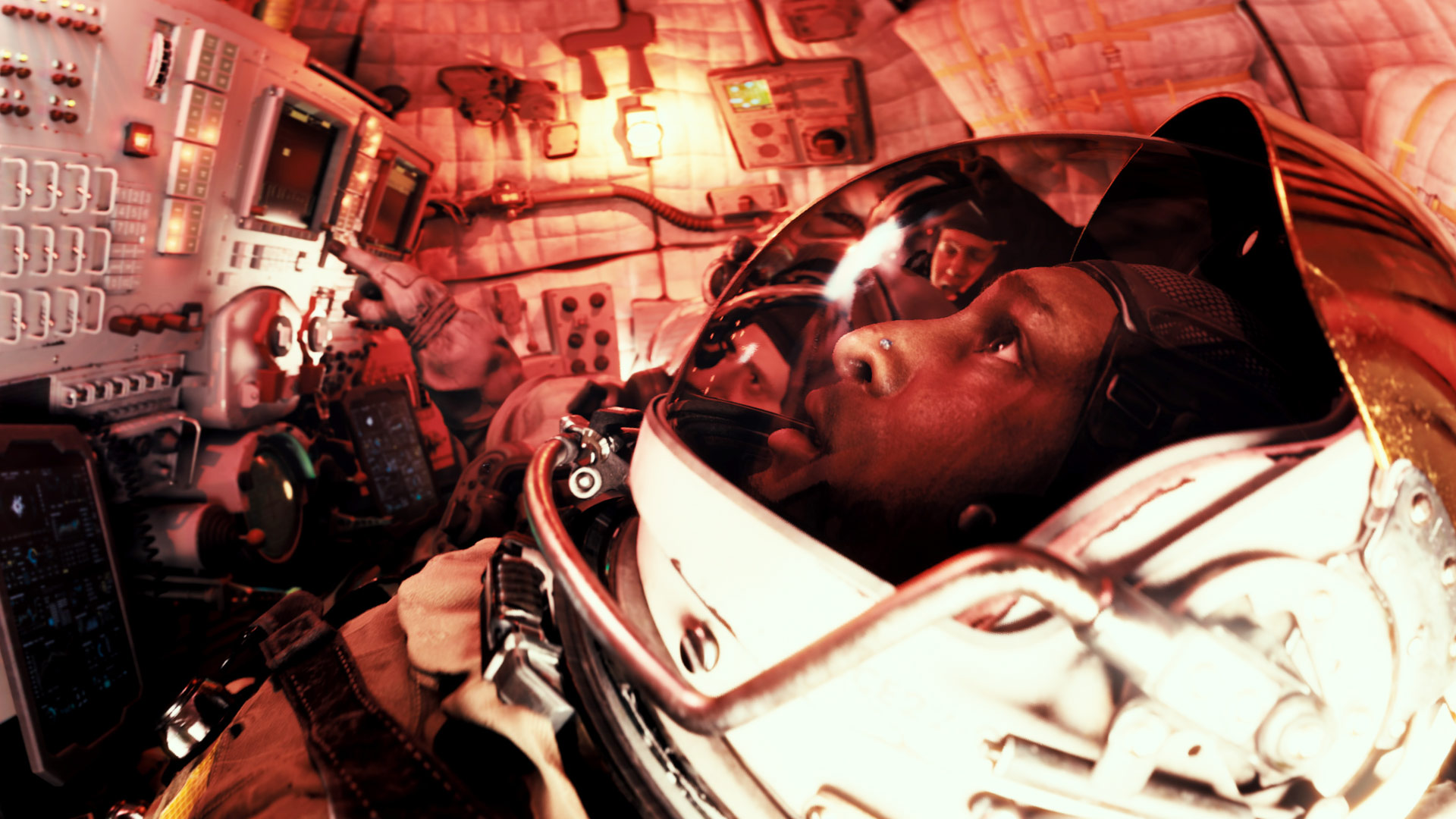

Asteroid

Asteroid is a short, space-set, high-end 180 video bookended by AI-powered interactive moments. Its lean, spectacle-driven plot centers on the ill-fated voyage of a vessel carrying strangers who head to an asteroid, intending to mine it and return home rich.

L’Ombre

L’Ombre is an hour-long mixed reality dance experience combining a handful of live performers, and a percussionist, with countless virtual extras and all sorts of incandescent digital scaffolding. It’s a France/Taipei co-production, inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s fairytale The Shadow.

Face Jumping

Face Jumping is a 30 minute production, set in a cartoonishly surreal bizarro world, that experiments with eye tracking as a form of navigation. Stare into a creature or person’s eyes and you’re transported into their body; after a while, you can literally throw eyeballs around to help make this journey more fluid.

La Magie Opéra

This 25 minute roaming experience takes a wonderfully creative approach to the history of Paris’ Palais Garnier opera house, dreamily folding together time and space, always prioritising the conjuring of magical moments over dry elements like dates and facts.

Collective Body

I’ve always been a self-conscious dancer, unable to fully embrace the spirit of that old line—”dance like nobody’s watching”—unless aided by prodigious amounts of narcotics. I did experience one exception recently, however, when I joined three others to participate in this communal dance production.

Alien Perspective

This astral-projecting experience sends us hurtling into the wild outer-space worlds of Italian artist Carlo Rambaldi, a three-time Oscar winner best-known for his animatronics and creature designs. It uses his paintings as world-building blueprints for striking, now spatialised environments.

Submerged

The first scripted video produced for the Apple Vision Pro is a 17 minute short set on a submarine, during WWII, where all hell breaks loose when a torpedo attack hits. Presented in super crisp 8K 3D, you can see the pores on the actors’ faces, and almost feel condensation dripping from the sub’s various dials and thingamabobs.

Ghost Town

Creaking floorboards, mysterious artifacts, weathered leather-bound books—these are the kinds of images that spring to mind at the mention of the word “supernatural.” In this puzzle game set in the 1980s, they’re more than familiar tropes; each is woven into richly atmospheric settings.

The Midnight Walk

Fairytale-esque narration is strewn throughout The Midnight Walk, with lots of talk of strange histories and recondite lores inside a Halloweenish world of perpetual night. It’s a strikingly stylised production that innovatively features digitally scanned, hand-sculpted clay objects.