Ari Aster’s Eddington pursues emasculation to the point of self-sabotage

Reporting from Cannes, we assess Eddington – which pits Joaquin Phoenix against Pedro Pascal.

Reporting from Cannes Film Festival, Rory Doherty sizes up Ari Aster’s new pic Eddington—which pits Joaquin Phoenix against Pedro Pascal in COVID America.

There is no symptom of COVID-19 that makes you prone to believe racist, anti-government, and anti-intellectual conspiracies, but enough people were coaxed away from reality by a grift economy peddling mistruths (and expensive supplements) about civil liberties and medical autonomy that, five years since a pandemic was declared, fascist delusion and naked profit-mongering has invaded nearly every tier of public and political life, with the culture and policy surrounding the novel coronavirus acting as a clear accelerant.

Assessments of the immediate bifurcation and distortion of our shared reality have already made it into print: Doppelganger is a 2024 nonfiction investigation by Naomi Klein into how the pandemic exacerbated government and medical scepticism on an internet-wide, highly profitable scale, creating “mirror worlds” online, in our communities, and in our homes.

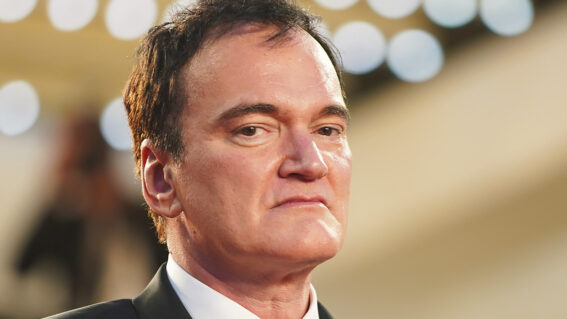

Ari Aster, whose zeitgeist-shifting horror films Hereditary and Midsommar were more psychological than politically driven, observes with Eddington many similar catalysts and toxins that have made modern life a real-world horror show. But even though a change of pace from his relentless shock tactics is welcome, the director struggles to interpret the recent political flashpoint without relying on his most tedious pet themes.

Related reading:

* Cannes 2025 preview: films to add to your watchlist

* Beau is Afraid is about mummy issues, sure – but it’s also about creation

* The highs and lows of Cannes 2024 – from the Palme to the panned

In May 2020, Eddington is a quiet New Mexican town with a level-headed but compromised mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal, perfectly cast as a genial local power player) who butts heads with Sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), a far more unlikeable and uncooperative figure in the town. Joe took over the job from his late father-in-law, and lives in a hostile home with his affection-resistant wife Lou (Emma Stone) and her grief-stricken, conspiracy-obsessed mother Dawn (Deirdre O’Connell). When Joe confronts his mayor in a supermarket over a recent mask mandate, he records a statement to explain his behaviour; the video doesn’t run for two minutes without him announcing a mayoral campaign.

This immediately irritates his personal life—Ted’s brief and ancient history with Lou seems to be a motive for Joe’s crusade against him; Lou berates him for inviting public attention on her during an extended bout of mental illness, which draws her closer to the beguiling online sermons of digital guru Vernon Jefferson Peak (Austin Butler), who claims to have reset his brain and unlocked foundational trauma.

Joe’s quest begins as a typical example of libertarian victimhood before it nosedives into typically vengeful Ari Aster waters, but throughout he is motivated by emasculation. He’s compared to Lou’s father by Dawn, and in every scene shared with Pascal and Butler, Phoenix stresses his character’s belittled and humiliated spirit. Despite his authority, Joe is symbolically cuckolded by Ted and Vernon, which is cross-generationally mirrored by a young graduate Brian (Cameron Mann), who watches as Ted’s son Eric (Matt Gomez Hidaka) hooks up with the girl Brian admires, Sarah (Amélie Hoeferle).

To Aster, whose prior film Beau is Afraid was an frustrating odyssey of Freudian paranoia, emasculation is a crucial key to decoding the world’s violence and misery, and in Eddington, he pursues it to the point of self-sabotage.

Women do not fare well in Eddington: Lou is a thankless role with no agency, a test subject under observation that Joe can’t communicate with, and Emma Stone and Austin Butler’s involvement becomes distracting when you realise how minor the characters are. Dawn bookends the film by listing unhinged conspiracies, which underlines not just how little Aster has given O’Connell but also the limits of the satire’s ironic remove.

Eddington’s main critique of its internet-affected personalities—both anti-maskers and a flock of Gen Z demonstrators incensed by George Floyd’s murder—is more concerned in pointing out insincerity than engaging critically but empathetically. Aster has made four films that shape reality to his characters’ most base and isolating fears to feel like we’re in safe, coherent hands. We are seeing the world as it was experienced fed back to us at a remarkably similar pitch and volume.

It’s especially disappointing as, in many regards, Eddington is a step forward for Aster. In an effort to ground us in a recognisable world, his compositions are far looser and less fussy, making it easier to get closer to his characters. The most exciting visual sequences—like when an armed Joe stalks his dark, empty town for a ridiculous and paranoid tactical mission—have a deliberate, dynamic, and authentically video game-like vibe that’s both refreshing and frustrating when the director refuses to give up his most obnoxious shock-factor motifs. Those with disabilities, schizophrenia, or experiencing homelessness are used purely symbolically and often as tools of humiliation—not a first offence for Aster’s social horror.

There is astuteness amidst Eddington’s tiresome stretches. Considering his previous subject matter, Aster has clearly thought about the contractions between QAnon’s fears of rampant, suppressed child abuse in a country as violent as America, and after acts of seismic violence pulls the rug out from under us, the last thirty minutes distorts Joe’s reality in a dizzying, cruel manner that feels like a truer representation of pandemic cognitive dissonance than the extended mask mandate material that opens the film.

If Eddington was solely mimicking the texture and sensation of COVID America, Aster may have been better off, as he’s far better suited to conjuring chaos than extracting meaning from it.

Originally published by Flicks on 19 May, 2025.