Cannes goes Peak Wes Anderson with the premiere of The Phoenician Scheme

Reporting from Cannes, we see how Wes Anderson’s latest illuminates how his House Style works.

Reporting from Cannes, Rory Doherty sees just how Wes Anderson’s latest illuminates how his House Style works.

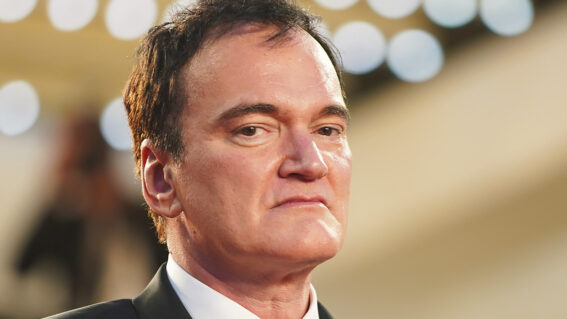

There are three stages to watching The Phoenician Scheme, a period espionage drama from Wes Anderson. First, the initial, welcome surprise that the King of Quirk has incorporated a classic thriller pulse into his beloved, idiosyncratic rhythms. Then, a sincere worry that the extended anthologised middle will drain your enjoyment. Finally, the rush of pleasure on discovering a third act that distills the film’s funny, exciting, and sensitive merits. Perhaps this is Anderson’s commentary on how the dreariness of financial schemes is more potent than the excitement of classic adventure movies; perhaps he doesn’t know when to stop being fussy with his stories.

After wowing in the first (and best) chapter in Anderson’s newsmagazine homage The French Dispatch, Benicio Del Toro takes centre stage as Zsa-zsa Korda, a ruthless magnate who amassed an eye-watering fortune by brokering shady deals (is there really any other kind?) between foreign powers and industrialists. When an organised cabal try to ruin his most titanic and dubious scheme, he begins a jet-setting quest to save his ass, accompanied by his only daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), who has rejected her controversial father by joining a convent, and Zsa-zsa’s new tutor, the eccentric and out-of-his-depth Norwegian Bjorn (Michael Cera).

Related reading:

* Cannes 2025 preview: films to add to your watchlist

* Cannes Dispatch: Ari Aster’s Eddington pursues emasculation to the point of self-sabotage

* The highs and lows of Cannes 2024 – from the Palme to the panned

The contrast between an early Wes Anderson film and a recent one is startling. All the precociousness, the mannered and rapid line delivery, and tightly-wound personalities (just begging to be unraveled) are all there from Bottle Rocket to The Phoenician Scheme, but at a certain point in his career, the manicured, dollhouse-like style explodes and expands across the frame, staunchly refusing to yield its territory.

Accusing Anderson of favouring “style over substance” doesn’t help us to understand why his production design, colour timing, and rigidly chapterised storytelling (to name only a few stylistic quirks) are so unmissable in recent years, but does this Peak Wes Anderson style work? In standout successes, such as in The Grand Budapest Hotel or Asteroid City, the filmmaker uses escalating artifice to delay emotional clarity, hiding his wounded souls behind finely coiffured performances and precise camera tricks. Like a magician, he reveals the timid, confused voices crying out for tenderness.

Have scholars deduced when Peak Wes Anderson began? Was it when he first used stop-motion in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou alongside a blaring Sigur Rós track to announce the ego death of its narcissist nautical navigator? Or in Fantastic Mr. Fox, where he was able to manipulate every glance, shrug, and twitch of his performers and returned to live-action filmmaking with a fever for meticulousness?

Maybe it’s hard for Wes Anderson to imagine a new genre-infused labyrinth of theatrical devices, only to plot a path to its soft, sensitive centre, knowing that even his loyal fans could dismiss it as “more of the same” if it doesn’t hit the highs of their preferred films.

The Phoenician Scheme makes superficial but meaningful tweaks to Anderson’s modus operandi: the Stravinsky soundtrack lends an orchestral intensity that matches the ’50s espionage emotions, and the colour palette boasts a softer blend of greys, blues, and green than the scorching yellow and crisp monochrome of Asteroid City—the sun is paler, more dubious here. By dialling up the suspense and action, Anderson intermittently captures the essence of classic espionage fiction, especially those that turned a cynical eye to business magnates in the post-war period.

The Phoenician Scheme is full of bureaucrat spies, self-serving industrialists, and a lot of chat about financial shares—it would be too generous to suggest this exposition is supposed to be tedious. Wes maps a faceless industrial scheme onto Zsa-zsa’s personal ambitions and insecurities, and Del Toro relishes the chance to play someone who’s both a petty tyrant (as a businessman and father) and a daring, assassin-dodging spymaster.

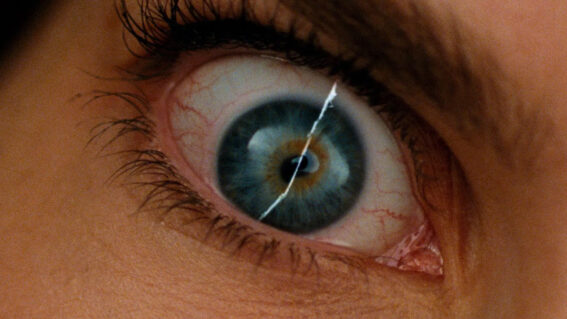

Because he’s a Wes Anderson protagonist, Zsa-zsa is also heavily hubristic, dismissive about fraught emotional rifts, and undermined by his sober-minded children. This last responsibility is ably handled by Threapleton, whose withering glare in a white novice habit with vibrant red lipstick and green eyeshadow (a colourful act of rebellious expression) is one of the film’s most striking visuals motifs.

It’s a shame that Anderson borrows The French Dispatch’s portmanteau story for its midsection, a series of rendezvous with obstinate businessmen refusing to save their broker’s hide, as the stopping-and-starting scene changes kills the thriller momentum stone dead. (Although Bryan Cranston and Tom Hanks in gymwear is a highlight.) As if worried about narrative stalling, Anderson kicks off the third act with a stunt that wakes the film up from a repetitive stupor and reembraces its quick and charmingly convoluted plotting.

As The Phoenician Scheme crescendos to its final chords, the alchemy of Late Anderson is laid out plainly—the sets, the dialogue, the onslaught of visual and aural stimuli are so intensified because, at the last possible minute, they will fall away entirely for his characters accept an honest purifying truth in the film’s palace of artifice. It’s a simple magic trick, but thankfully the filmmaker hasn’t lost his touch for it.

At times our confidence is shaken, but The Phoenician Scheme reaffirms the joy of discovering something tiny and human tucked away in Anderson’s dollhouse.