Hamnet brings Shakespeare back to the Oscars race – but can it really explain the Bard?

Oscars buzz surrounds the release of Hamnet, which chooses a bold, female-first approach to exploring Shakespeare’s life and work.

Anne Hathaway (no, not the actress—the wife of William Shakespeare) makes no appearance in Shakespeare in Love, although if we are to take the rakish, lovestarved William Shakespeare’s word for it, she’d have little to contribute to his story. As the Bard (Joseph Fiennes) pursues the lovely Viola de Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow), Hathaway remains back at Stratford with their children. Their loveless marriage remains a bugbear for the genius poet; Will’s attempts to handwave away an entire wife and family temporarily upsets his courtship of Viola.

Since sweeping the Oscars 27 years ago—perhaps the ultimate symbol of Miramax’s bulldozer approach to awards campaigns—the frothy, winking historical romance has continued to frustrate and bewitch another generation of film fans. It’s devoted to extracting the charm, whimsy and intensity of Shakespeare’s oeuvre, but can only pay homage by cheekily imagining episodes in his own life that gave direct, literal inspiration for scenes and dialogue.

Shakespeare in Love is bluntly titled and designed, and its broadness has been consistently critiqued over the years. Intentionally or not, the film agrees with one contested branch of historical thinking: that Shakespeare and Hathaway’s marriage was unhappy, and by extension Anne contributed little to the Bard’s prolific genius. (After all, what kind of a muse is bequeathed “second-best bed” in the will of her devoted poet?)

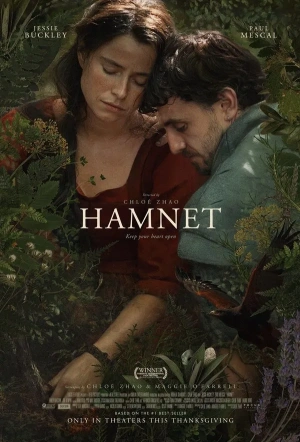

If Chloé Zhao’s Hamnet is interested in any of the omissions and oversights of 1998’s most awarded feel-good hit, it’s the scorn shown to Hathaway. Based on Maggie O’Farrell’s 2020 novel, Hamnet focuses on Agnes Hathaway (Jessie Buckley), a young Stratford woman with a sensual affinity for the wild world. She trains a hawk, she mixes herbs, she loses herself in the tall trees and gnarled roots of the English forest. As Agnes and Will (Paul Mescal) build their family, her spirituality is increasingly swallowed by the momentum of Will’s career; he moves them into a large country house but frequently disappears for theatrical opportunities in London.

The couple’s only son Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) dies young from the plague. Will is unwilling to confront his grief in any form except his writing, and Agnes’ severance from the spiritual, natural world feels especially pronounced now that she’s been robbed of a child. When Will (“Shakespeare” is never mentioned in the film) begins work on his tragedy about a Danish prince (as a prologue quotation reminds us, “Hamnet” and “Hamlet” were essentially interchangeable names in Elizabethan England), Zhao underlines the pained but direct channel from grief to art.

Hamnet shares a main character, historical setting and key locations with Shakespeare in Love, both stories taking advantage of how little we truly know about Shakespeare’s inner life. But where the latter offers a playful romp filled with knowing winks toward Romeo and Juliet’s iconic moments, Hamnet is more naturalistic and, at times, uncomfortable. All the inside baseball references to Shakespeare’s folio feel less like winking, and more melancholic.

Films about how writers came up with their most famous texts are often staggeringly uninteresting, forced to condense and flatten a work of art into an abstract “greatness” that, for some reason, has to be explained by extraordinary real-life circumstances in order to be understood. Neither Hamnet nor Shakespeare in Love are immune to this problem, and neither are as thorny or impressive as the plays created within them.

Still, both films acknowledge the same truth: Shakespeare’s cultural ubiquity exists alongside a near-total absence of personal record, and fiction remains the only way of reaching a fuller, more satisfying experience. There’s a desire to complete the Bard’s life, outside his work. In Hamnet’s attempts to centre a woman too easily dismissed in retellings of William’s talent, O’Farrell and Zhao express a dissatisfaction with the received wisdom of Anne Hathaway’s status as someone incidental to Will’s career and expression. In one scene, Agnes watches the play that Will has abandoned his family to create; rather than excusing his neglect, she is afforded clarity about it.

Agnes is no better treated as a wife by the film’s end, but she becomes part of Shakespeare’s audience, recognising that if she wants insight into the man she loved, this is where she must be. Her journey mirrors the audience’s: can we truly understand this man? Hamnet suggests that we may never fully do so—that understanding Shakespeare through tiny scraps of history may be a lost cause. In Hamnet, he tells Agnes along with the audience to look for his soul in his plays.