Retrospective: in the age of augmented reality, cult classic They Live is an even wilder film to rewatch

“I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic They Live is always an interesting film to revisit—but especially now, during the early years of augmented reality, writes Luke Buckmaster.

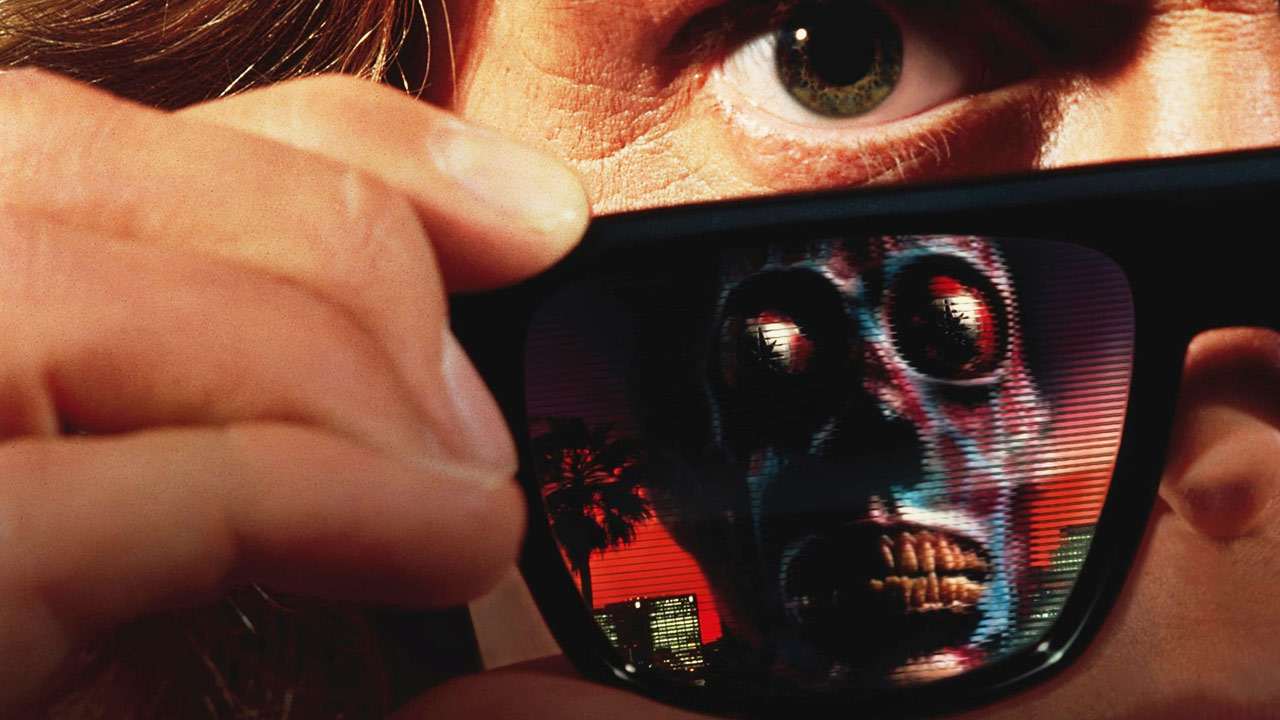

In Free Guy, Ryan Reynolds discovers a pair of sunglasses that reveal the world for what it really is: a video game like Grand Theft Auto, where he can do anything—fight bad guys, fang it on motorbikes, die in sensational explosions—and there are never any consequences. In John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic They Live, Roddy Piper also dons a pair of sunglasses that reveal what the world really is: a capitalist hellscape run by freaky-deaky aliens who walk in disguise among us, keeping us under control by brainwashing the population with subliminal messages.

No prizes for guessing which of the two is edgier, cooler, and destined to stand the test of time.

They Live is one of those titles that might initially have seemed dispensable and junky—one critic, not entirely unreasonably, described it as “pop Orwell”—but only grew in the public consciousness as the years rolled by. Its subversive anti-capitalist messages echo the text printed on one of my favourite and most cheerful t-shirts, which simply reads WORK BUY CONSUME DIE. Plus it has one of the greatest one liners in action movie history: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

That line is delivered by John Nada (Piper), a drifter who is homeless and out of luck, arriving in Los Angeles in the hope of starting afresh—only to unearth the truth that humankind is dominated by the aforementioned aliens, which in their naked form resemble skeletons covered in a thin layer of blue and red skin. Early on he encounters a preacher in a public park, going off-script from the Good Book, ranting about how “they have taken the hearts and minds of our leaders, they have recruited the rich and the powerful and they have blinded us to the truth…” The subsequent film mounts a case that the crazy guy in the park was right all along.

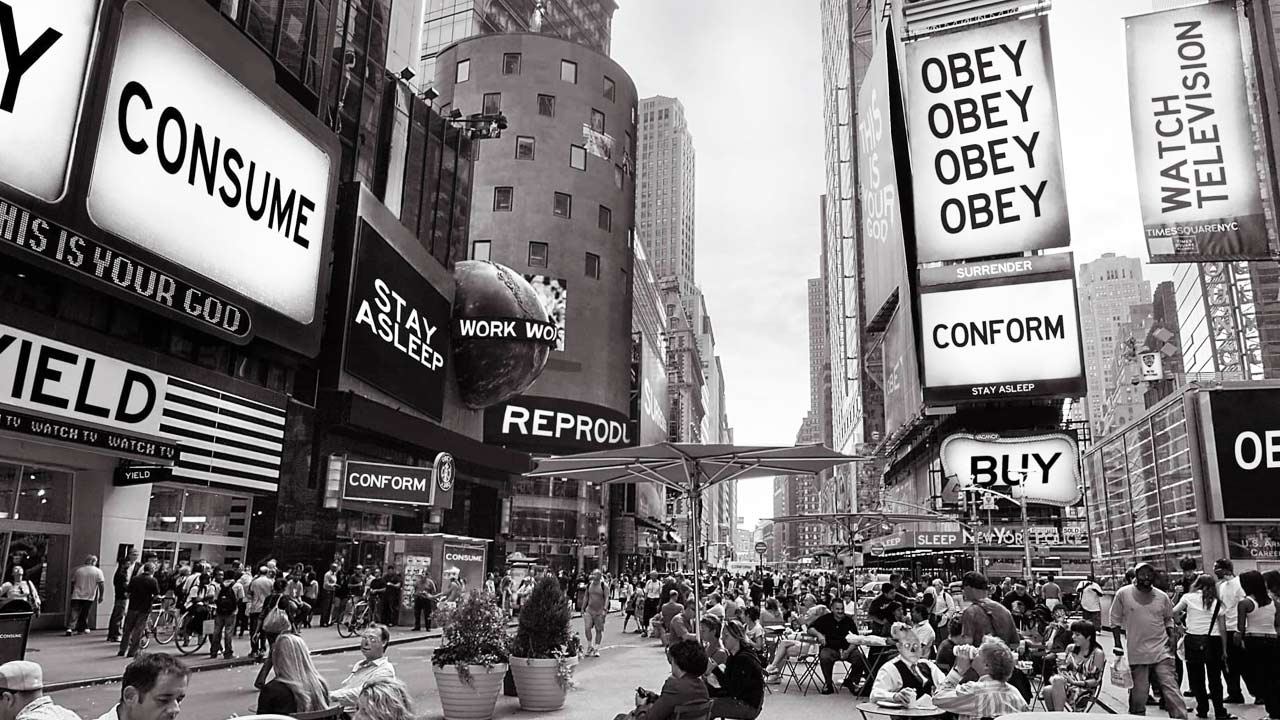

The first half hour is all set up, leading up to the moment when John dons the nondescript black sunglasses for the first time and can now see the “truth” around him—a conspiracy theorist’s wet dream. Through his reality-piercing lens, a billboard advertising computers simply reads OBEY in big black letters. A billboard depicting a sexy woman in a red bikini reads MARRY AND REPRODUCE. A sign for a men’s apparel store says NO INDEPENDENT THOUGHT. Bank notes are stamped with the words THIS IS YOUR GOD.

Carpenter delivers his critique on consumerism, neoliberalism and the media with the kind of subtlety the above description implies—which is to say, none at all. When addressing its messages around issues such as inequality and media corporatization, Carpenter himself has been, like the film, as delicate as a sledgehammer to the face.

“It’s a documentary, it’s not science fiction,” he told Yahoo! in 2015. When internet Nazis attempted to co-opt the film in 2017, the director tweeted: “THEY LIVE is about yuppies and unrestrained capitalism. It has nothing to do with Jewish control of the world, which is slander and a lie.”

Adapted from a short story by Ray Nelson titled Eight O’Clock in the Morning, the premise is perfect for the motion picture medium, packaging political commentary in the form of visual reveals. John sees the ‘real’ meaning of advertising as well as which ‘people’ around him are really camouflaged aliens. The continued relevance of They Live’s political themes makes it an always-evergreen film to return to, but there is another element that makes it interesting to revisit in the current cultural moment: the rise of augmented reality technology. AR is also about using lenses to see the world differently.

Like virtual reality, nobody knows exactly where AR will take us—though we do know that we are in an early period in its evolution. Last month Facebook launched its first line of smart glasses, with many other varieties on the way, including from the likes of Snapchat. The promotional video advertising Snapchat’s snazzy spectacles promises to enhance human experience by showing us a whole lot of trippy stuff that isn’t actually there, such as psychedelic bubbles and sea creatures. What the video doesn’t speculate on is the kind of advertising that will almost certainly be emblazoned in front of our eyeballs once the technology takes off.

One memorable short film from 2009 envisioned a nightmarishly augmented world of the future, where layers upon layers upon layers of advertising terrorise our day-to-day lives. If anything remotely like this vision comes to pass, it will, in the context of They Live, present an ironic inversion of Carpenter’s concept. Instead of glasses being used to see through illusions and observe the dirty underbelly of reality, they will instead further clog our senses with stimulus, adding to rather than subtracting layers of unreality.

In other words: They Live’s augmented reality glasses cut through the bullshit, while the real kind may clutter our vision with more and more of it.

Some, like the makers of the video above, imagine this as a kind of living hell, continuing a trend of discourse that has existed since time immemorial—of greeting any major new technological advancement with skepticism or distrust (or even technophobia). This goes all the way back to at least ancient Greece, with Plato being famously skeptical of the invention of writing, arguing that putting something on paper weakens one’s memory. On that point the dude was admittedly right; god knows what he’d think of Twitter.

Nevertheless, augmented reality offers many thrilling possibilities. It could be just a matter of time for instance before some clever programmer makes a They Live AR ad-blocker, which visually transforms advertising on our computers, TVs, and phones into displays of ominous single worlds such as OBEY and CONSUME. I’d use that, for sure. And if it ever displayed the people around me as aliens, it would be time, of course, for chewing gum and kicking ass—with or without the gum.