Palme d’Or winner Julia Ducournau returns to Cannes with blunt, uncompromising Alpha

Alpha pointedly denies us the liberation of transformation central to the body horror genre.

A teen comes home with a recklessly-applied tattoo during an era of a lethal blood-borne disease in Julia Ducournau’s Alpha. Reporting from Cannes, Rory Doherty considers how this new film, with less of an emphasis on body horror, sits among the Palme d’Or winner’s work.

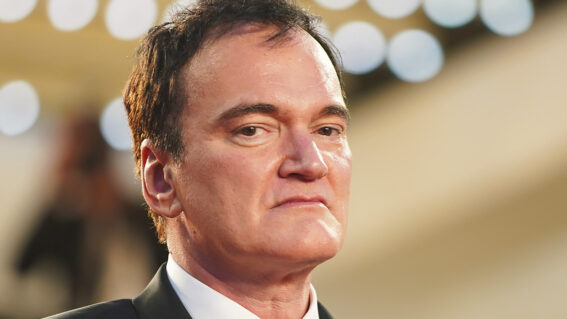

Julia Ducournau has followed up winning the Palme d’Or with a film that sees sickness and memory as hungry urges equally capable of driving us off the edge. The French filmmaker debuted nearly a decade ago with Raw, a cannibal bildungsroman that made a (dental) impression for its brazen, bloody story of sisterhood. Then in 2021, Ducournau was handed the top Cannes prize by Spike Lee himself for Titane, her moving thriller about a car fetishist fleeing serial murder charges and adopting the identity of a grieving fire chief’s missing son.

In Alpha, Ducournau returns to the body as a site for painful, intimate sensation, but evidence of body horror is solely located in drab, unsensational environments—hospital gurneys, the mattress on which an addict waits out withdrawal, or the classroom where 13-year-olds dub you a dangerous freak for bleeding when you shouldn’t.

Related reading:

* Cannes 2025 preview: films to add to your watchlist

* Cannes goes Peak Wes Anderson with the premiere of The Phoenician Scheme

* The highs and lows of Cannes 2024 – from the Palme to the panned

Alpha disguises none of its commentary: this film about sharing a fear for illness uses the visual shorthand, cultural reference points, and painful timeline of the AIDS crisis as guideposts for the story of young Alpha (Mélissa Boros), who terrifies her doctor mother (Golshifteh Farahani) after being marked by an amateur tattooist at a reckless teenage party.

It is 1990 and a lethal blood-borne disease has a stranglehold on the medical world (we know gay men and substance addicts are particularly vulnerable), and the virus takes over the sufferer’s body until it calcifies them entirely, turning them into smooth, solid marble. Hospital wards overrun with patients slowly morph into morbid sculpture studios—the marble flesh cracks and caves when examined, the blood underneath turned to a red dust you’d find on the surface of Mars.

One longtime sufferer is Amin (Tahar Rahim), Alpha’s estranged addict uncle who returns suddenly to recuperate with both mother and daughter. The magnetic charge between the three family members is, along with the fear and manifestation of Alpha’s sickness, the main driving force of Ducournau’s story, which has been plotted out in far more strenuous and deliberate terms than the bracing adrenaline rush of Raw and Titane.

This is a fault with the film, as the volume and volatility of Alpha’s relationships rarely lowers across the two-hour runtime. The split narrative detailing her school life, ties to her Moroccan family, and yellow-tinged flashbacks to her mother balancing Amin’s condition with the marble disease outbreak eight years prior—it’s a busy plot for a family drama. Alpha is filled with lines poetic enough to melt on your tongue, but the intensity of discomfort throughout the film (captured in rocking, handheld shots of grey, dim interiors) can render sections of Alpha’s midsection overwrought and exhausting.

That said, this directness could be understood as a symptom of Ducournau unshackling herself from the established tenets of genre cinema from her previous films. Alpha tries very hard to express something horrifically real, and even though Titane’s abstracted themes of transness gave us a more shifting and sophisticated text, there’s a blunt, uncompromising power to Ducournau removing the distance between Alpha’s metaphors and the reality it confronts. Ducournau gets straight to the visceral pain of watching people you love turn into something heavy, brittle, and useless, pointedly denying us the liberation of transformation central to the body horror genre.

This is a film about AIDS, but it is also a film not literally about AIDS, but rather how diseases like it affect the membranes of family ties committed to memory. Alpha shows a warped, immediate and messy version of history: public housing is layered in thick, unnatural red dust, cutting bigotry lingers in the paranoid discussions of the marbled victims. There are parts of Alpha’s Berber extended family history that they do not talk about, even if the same crisis keeps cropping up in front of them. This is the future, and this is the past.

In Ducournau’s films, sisters, mothers, fathers, daughters are connected organically, and these relationships have immune systems that try to flood out infection. Alpha initially rejects her unstable uncle, soon their symptoms begin to synchronise, and only he and her mother are able to rescue her from totalic, reality-warping nightmares. The scenes where Alpha hallucinates or lashes out in panicked frustration are the parts of Alpha that best showcase Ducournau’s talent for intense and emotionally revealing filmmaking.

At a point in Alpha’s final act, Ducournau drops some well-worn, sleight-of-hand reveals that risk feeling too tropey, but can be forgiven by the piercing vulnerability and clarity that Alpha, her mother, and Amin pull each other into as a consequence. There’s the sense that Alpha and Ducournau end up in similar positions: we do not know how the past will hold onto us, how it will affect how we see those around us, and attempts to excavate it will be messy, arduous, and vulnerable. Alpha‘s willingness to show so much pain may be off-putting, but it’s Ducournau’s way of inviting us closer than she’s ever done before.