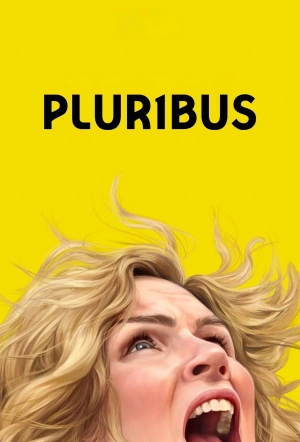

Pluribus rewrites the end of the world with a blissfully strange twist

What if the end of the world felt…kind of lovely? The new show from the creator of Breaking Bad creates a truly genre-breaking apocalypse.

Charles Dickens opened A Tale of Two Cities with one of the most famous sentences in English literature, starting, of course, with that wonderfully punchy contrast: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…” In the real world, with wars raging, oceans rising, inequality growing, and democracy looking like it forgot to install a software update, Dickens’ line, if I’m reading the mood correctly, fits our era pretty well—if you lop off the “best of” part. Even glass-half-full types surely see the current moment as one synonymous with a feeling that rules are being rewritten, all bets are off, and big changes are inevitable.

All of which makes it an excellent time for the arrival of Pluribus. The new series from Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan offers a fresh perspective on Dickens’ clash of opposites. It’s set in a post-apocalyptic world smashed by an alien virus that’s infected almost all the Earth’s population: the worst of times! Butttt, this virus is nothing like a zombie infestation; in fact, it makes all infected parties feel truly happy and at one with the world. The best of times?!

The protagonist, best-selling romantic-fantasy author Carol (Rhea Seehorn), doesn’t see it like that. But then again she wouldn’t, being established from the outset as a colossal grump and misanthrope. We meet her at a book signing, before the outbreak hits, where she’s friendly and welcoming—but it’s all a show. When a chauffeur notices her adoring fans and asks whether he should know who she is, Carol returns with a counter-question: “You a big fan of mindless crap?” Soon after, in a bar with her wife Helen (Miriam Shor), she condemns the idea of celebrating a book tour: “You endure it; you do not toast it.”

Carol is the person most in need of a crazy phenomenon that can turn her frown upside down. But the gods are not without a sense of humour, and soon she’s the saddest person on earth—for real this time—everybody else permanently chuffed, with their alien-virus-induced harmony (I was initially going to write “alien-virus-induced lobotomy,” except they’re actually smarter than before, united in an all-knowing collective consciousness—though I won’t divulge too many details). The performances from the many “infected” people are clever: they have big smiles on their faces, but these smiles aren’t cartoony or mischievous. They’re smiles that say: “I am content, I am at peace, all is right.”

Perhaps the show’s most interesting tonal achievement is that it’s funny—usually funny-weird, sometimes funny ha-ha—but never in ways that jolt you out of the story or reduce the stakes. The comedy mostly revolves around the very different wavelengths of Carol and her…captors? She feels, for good reason, trapped by these strange creatures, who now rule the world and call the shots. On the other hand, they give her anything she wants, like genies granting wishes: beautiful meals, big homes, drugs, hand grenades, whatever.

Understanding the temperament and ideology of the aliens (if we can call them that) is one of the show’s great pleasures. I’m tempted to draw on examples to prove the point, but these are best left for Gilligan et al. to divulge. At one point, in the second episode, Carol has one of her semi-regular bursts of exasperation, screeching: “I’ve seen this movie. We’ve all seen this movie, and we know it does not end well.”

But have we? Her mind is probably jumping to a thousand zombie flicks or maybe that seminal title of pandemic horror—Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The 1978 version concluded with an image brandished like a hot iron onto our collective psyche—Donald Sutherland’s face contorted into an Edvard Munch-esque scream, his soul finally snatched. But Pluribus is a very different kettle of fish; the unexpected twist in its premise raises questions (like: is the invasion really a bad thing?) that change the game, allowing Gilligan and his writers to approach an old sci-fi conceit with a new set of tricks. Maybe the best and worst of times can be indistinguishable when the world rewrites its own rules.