Retrospective: High Noon is the greatest western – and it’d be called ‘woke’ these days

The 1952 classic is still powerfully modern with its pacifist hero, anti-gun message, and fierce female characters.

Released during the height of Hollywood’s anti-Communist panic, 1952’s High Noon remains a thoughtful, deeply political classic of the western genre. Luke Buckmaster unpacks the story of a hero who sees violence as a bitter last resort.

For me, westerns never got better than High Noon: Fred Zinnemann’s convention-shattering classic starring Gary Cooper as a small town sheriff nervously awaiting the return of a hoodlum determined to kill him. Shoot first, talk later was always the style of chest-beating law enforcers in the cinematic wild west, but this film proposed another way: a protagonist who thinks things through, consults widely, and turns to violence as a last resort. It’s not just a movie per se but a kind of cultural conversation, responding to countless morally simplistic stories about trigger happy sheriffs propped up by spurious notions of “frontier justice.”

High Noon would be called “woke” if it were released these days, because it has strong female characters, interrogates the values of small town America, and even hints at an anti-gun message—a helluva bold move in the genre of stirrups and shootouts. The gun skills and derring-do of Cooper’s Will Kane match any John Wayne character, but he brings something else: a rare kind of humanitarianism. Wayne himself, a fierce conservative and member of a communist-hunting Hollywood organisation, slammed the film for being “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life.” Them god darn Reds made a movie!

High Noon only really has one action scene, right at the end, when the vicious Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald) finally arrives on the noon train, bringing to a head a suspense-dripping storyline that unfolds in real-time. It begins understatedly, on the outskirts of Hadleyville, where three crooks are waiting for the train that will return Miller to the town he once ruled. We hear the film’s theme song, which is psychically connected to Kane—a projection of his emotional state—famously beginning: “do not forsake me oh my darling, on this my wedding day.” The song and score (composed by Dimitri Tiomkin, with lyrics by Ned Washington) are used to great effect going forward, adding atmospheric zhuzh while returning the film to Kane’s state of mind.

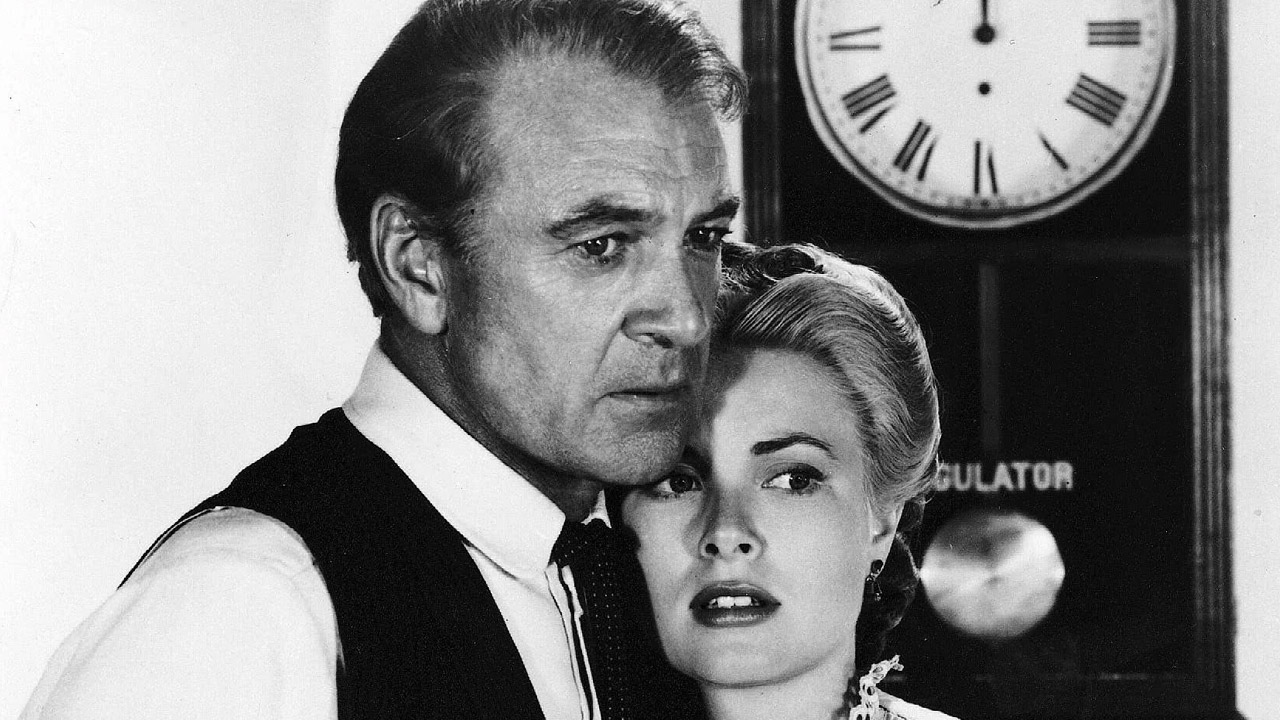

We meet Kane on, indeed, his wedding day, as he’s married to Grace Kelly’s Amy. Celebrations are cut short when news breaks that Miller is en route. This poses a conundrum for the protagonist: to run away, or stay and fight? Amy pushes for the former but of course he chooses the latter, commenting that “I’ve never run from anyone before.” Much of the film consists of Kane walking around town attempting to rustle up support, asking men to help him stand up to Miller and his gang.

It doesn’t go well. The judge bolts; Kane’s deputy quits. Blokes at the bar look stony-faced when he asks “how ‘bout it?” This plotline crescendoes when the protagonist addresses a packed congregation at the local church, his request for help prompting much debate and naysaying. This great scene features a stunning betrayal from his friend Mayor Jonas Henderson (Thomas Mitchell). Henderson’s empathic about the great things Kane—“a mighty brave man, a good man”—has brought to the community, asking churchgoers to “remember what this town was like before Will came here” and describing Miller’s return as “our problem, because it’s our town.” All good so far. He implores the townspeople to “have the courage to do the right thing, no matter how hard it is.” Even better.

But then the Mayor segues from discussing what’s morally right, to what’s smart, inadvertently making a point that they are often not the same thing. When Miller arrives, “there’s going to be a fight,” he says, and “someone’s going to get hurt.” He predicts that news of the violence will make its way to potential investors who’ve been “thinking about sending money down here” but will be put off and “everything we worked for” will be lost. However if the sheriff’s not there when Miller arrives, “there won’t be any trouble.” So, he concludes—a gobsmacked Kane standing next to him—“the only way out of this” is for Kane to “go while there’s still time.” The film is partly about standing up for what’s right when everybody is telling you not to.

At the periphery of the narrative is the Mexican businesswoman Helen Ramírez (Katy Jurado), who predicts Kane will die and “when he dies, this town dies too.” Her prediction is partly wrong, but right in that Hadleyville’s soul is on the line. Katy Jurado’s performance as this great, fiercely strong character is amazing; she has eyes that burn through the screen.

Another classic moment is also a simple dialogue exchange, this one between Ramírez and Amy. When their conversation broaches guns, the film expresses an anti-gun message, with Amy reflecting that: “My father and my brother were killed by guns. They were on the right side, but that didn’t help them when the shooting started. My brother was 19. I watched him die.”

Many westerns are flashier than High Noon, the incredible works of Sergio Leone being obvious examples. But form never trumps ideology, and few other tales of the wild west solicit anything close to the impact of High Noon: a film that gets its moral messaging exactly right. It’s pared-back and powerful, and never gets old.