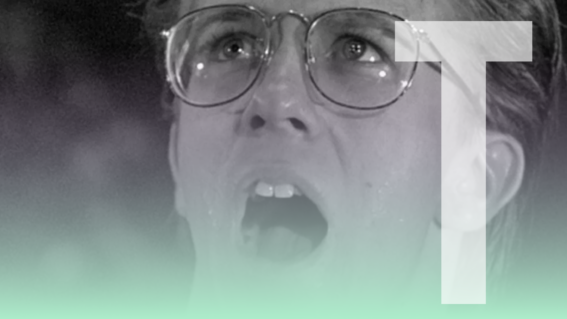

‘Cartel Land’ Director Matthew Heineman on the Film He Risked His Life to Tell

Oscar-nominated documentary Cartel Land is a fascinating, gripping, and often terrifying journey to both sides of the porous US-Mexican border in an examination on how the drug trade affects locals. Unflinching in its depiction of citizens taking matters into their own hands where their governments cannot, Cartel Land is out now on DVD and premieres […]

Oscar-nominated documentary Cartel Land is a fascinating, gripping, and often terrifying journey to both sides of the porous US-Mexican border in an examination on how the drug trade affects locals. Unflinching in its depiction of citizens taking matters into their own hands where their governments cannot, Cartel Land is out now on DVD and premieres on Rialto Channel on Thursday April 21st at 8:30pm. Director Matthew Heineman joined us for a chat about his unmissable film.

FLICKS: What’s it been like for you since the film has been playing globally over the past year?

MATTHEW HEINEMAN: Its first showing was over a year ago, so it’s been quite a journey with the film and I’m sort of slowly winding down from fully working on it. But honestly, I risked my life to tell this story. I care deeply about the issues and the people in the film. And so it’s something that I keep track of, and I keep tabs on, and I’ll continue to do so for a very long time.

Having embedded with people in very intense circumstances, what sort of emotional bonds have you formed?

Obviously, this is a complicated film to make on many different levels. It’s showing people doing complicated things, different shades of morality. But at the end of the day, you create a bond with people even though you might not necessarily agree with what they’re doing. And without that bond, without that trust, I wouldn’t have been able to get the access that I was able to get. And they were risking their lives to “fight for what they believe in” and I was tagging along with them, risking my life and the life of my small crew. So, I think there was a lot of respect that came with that. It’s also helped get them to tell the story.

Is it difficult having a personal connection to people who are still in harm’s way every day?

Even though I was in harm’s way and even though I was in shootouts, and intimidated, and surrounded by people, and had all sorts of close calls, at the end of the day I would fly home to New York. The real tragedy and the real horror is not mine, it’s of the innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. The innocent citizens living in a society where government institutions have failed. And in a society where essentially cartels rule with impunity. That’s the world that I entered, and that’s the world that I left. But that world continues without me there, without my camera there. And unfortunately the tragedy that we see in the film has continued, murderers have continued, and in many ways things are worse off there than they were before this movie started.

Has the process of making the film changed your attitude toward recreational drug use? Is it difficult to contemplate recreational drug use after seeing first hand some of the effects?

Yeah, I mean, the elephant in the room, and one of the reasons I made the film, is that we’ve become obsessed with ISIS and we’ve become obsessed with all these conflicts around the world. But here we have this conflict that’s right on our doorstep and it was a country that we share so much history with. Our neighboring country. And the conflict that we’re tied to, that was fueling the consumption of drugs here in the US. And it’s more complicated than that, but at it’s basic level, it’s basic supply and demand. As long as there’s the demand for drugs in here there’ll be a supply of drugs coming from Mexico and South America, and with the violence, and with that the cycle of corruption and horror that we see depicted in the film.

Since 2007, 100,000-plus people have been killed, 25,000-plus people disappeared. And that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to make the film, was to sort of shed light on that. I think one interesting anecdote that’s happened at numerous viewings– mainly in the U.S., are people coming up to me bawling and crying, saying that they’re addicts and that their brother, and mother, or sister, or father, whomever has been begging them to quit. And they couldn’t, but for some reason seeing Cartel Land and seeing the results of their personal choices on people. And the violence that their personal choices inflicted on these people had a very profound impact on me. That was a reaction that I never could have really imagined or predicted.

It’s very hard to think of just the topic of drugs and legality and morality as singularly a health issue.

It should be thought of as a health issue. I mean, I didn’t make Cartel Land as a policy film, I made Cartel Land to provide a window into the world in which this conflict plays out. To put a human face to this conflict. This is not a policy film, but I think something’s missing in the policy films and policy discussions and policy articles, or policy news reports. We get caught up in legalization, which is an important discussion to be had, but it’s equally as important to be discussing this as a public health issue and pouring money into treatment and other things and trying to fight the war of addiction as opposed to fighting with guns and billions of dollars that are wasted on building fences and other things.

You mentioned you could go back to New York before, during, after making this film. For us in New Zealand, the cartel reality is even further. We’re an island country. What sort of conclusions do you think we could draw from the film? Considering the things in it aren’t happening right on our doorstep, like they are for you.

I think the film is as much about human nature as it is about the drug war. What happens when governments are up for sale? What happens when there is deep corruption embedded in government institutions.? It’s about what happens when citizens take the law into their own hands. It’s about what happens when groups fail to function. It’s about so many things other than just the drug war. It just happens to take place in the context of the drug war, but it’s about so many other things. It’s about what happens when power corrupts, what power does to people, what guns do to people. So I think the film hopefully plays on many different levels, outside of the sort of policy context of the drug wars. So I guess it’s up for you guys to decide, what you want to take away from it.

I was trying to find a comparison to another sort of historical period. Is this like the western frontier? Is this like the medieval period? Can you draw a comparison with another place or time?

I’m not a policy expert, and I’m not a history expert. I tried to make a film, an experiential film, following a story that really fascinated me. My last film was on healthcare in the U.S., and I spent eight months doing research before I even turned on the camera. I turned on the camera here immediately, so it’s a different type of film. That being said, the most apt comparison to any place is Columbia, for sure. In some ways, Cartel Land is where Columbia was decades ago, with their para-military groups. So whether Mexico heads in the direction of Columbia, who knows, but there are a lot of parallels and similarities between Columbia years ago and Mexico today, especially in the context of the outer defenses and the para-military groups.

The locals aren’t necessarily overly enamoured with the para-military “assistance”. One gentleman is filmed talking about the fact that they aren’t the state, aren’t an arm of the state, and therefore even as a citizens’ defense force it doesn’t have any legitimacy. I found that a very interesting moment.

Yeah, I think that’s seen as one of the big turning points in the film. It’s a very important scene. I always joke, and it’s probably not a good joke to use and you might not even know who he is, but we always joke with the editing that the guy, we call the guy Charlie Rose. He asked all the questions that we wanted to ask but we don’t have a narrator or a host or anything. He asked all of these questions that we were all wondering. “We gave you the power, who do you think you are? Why are you bothering us? And it led, it was a very crucial turning point in the film.

Obviously there are many, many times in the film where you were in harm’s way or there was a strong likelihood of being in harm’s way. Among all those threats, was there one particular threat that you were more concerned about?

You know, I think this threat was present at all times. There’s no sort of Green Zone, no safety zone. And that’s the world in which these people live. Violence can erupt at any moment. It can be mundane, driving in the back of the car with the doctor, with a bullseye on the back of his head. That, in itself, is just scary. There are countless times when I was surrounded and threatened by people with masks and guns. There are obvious situations of danger and being chewed out in torture chambers and meth labs and all the things like that.

Despite all those moments, one of the scariest moments for me was the interview that I did with a young woman who was kidnapped along with her husband and witnessed him being burned to death, and chopped up to pieces in front of her. Being in this room with this woman, and seeing her – the cartel had sucked the soul out of her. Her body was there, but her soul wasn’t. And that sort of sadism with which they said, “You will live, but you will go mad,” and to think that as the same species, as human beings, they would do that to other people, that sort of mentally stuck with me. That’s stuck with me more than anything else.