Ballard might be a spinoff, but she’s not just Harry Bosch in different clothes

Boschverse show explores the ugly underbelly of L.A. with a sharper, more modern edge than typical noir.

A spinoff from some of the modern era’s best noir storytelling lives up to the shows and characters that preceded it, covering new ground in Ballard – streaming on Prime Video. Daniel Rutledge considers how the new show fits the Bosch template in places and departs from it elsewhere – to winning effect.

After more than a decade of TV centred on Harry Bosch protecting Los Angeles with a righteous scowl and dogged integrity, he’s passed the baton. The original Bosch series gave us a hard-boiled detective in the classic noir tradition, then in Bosch: Legacy he put those hard-won instincts and an unshakable moral code to use, following him as he left Hollywood Homicide and worked as a private detective. That spinoff smartly handed some of the emotional weight to his daughter Maddie, but now we have our first Boschverse show that doesn’t have Bosch at its centre.

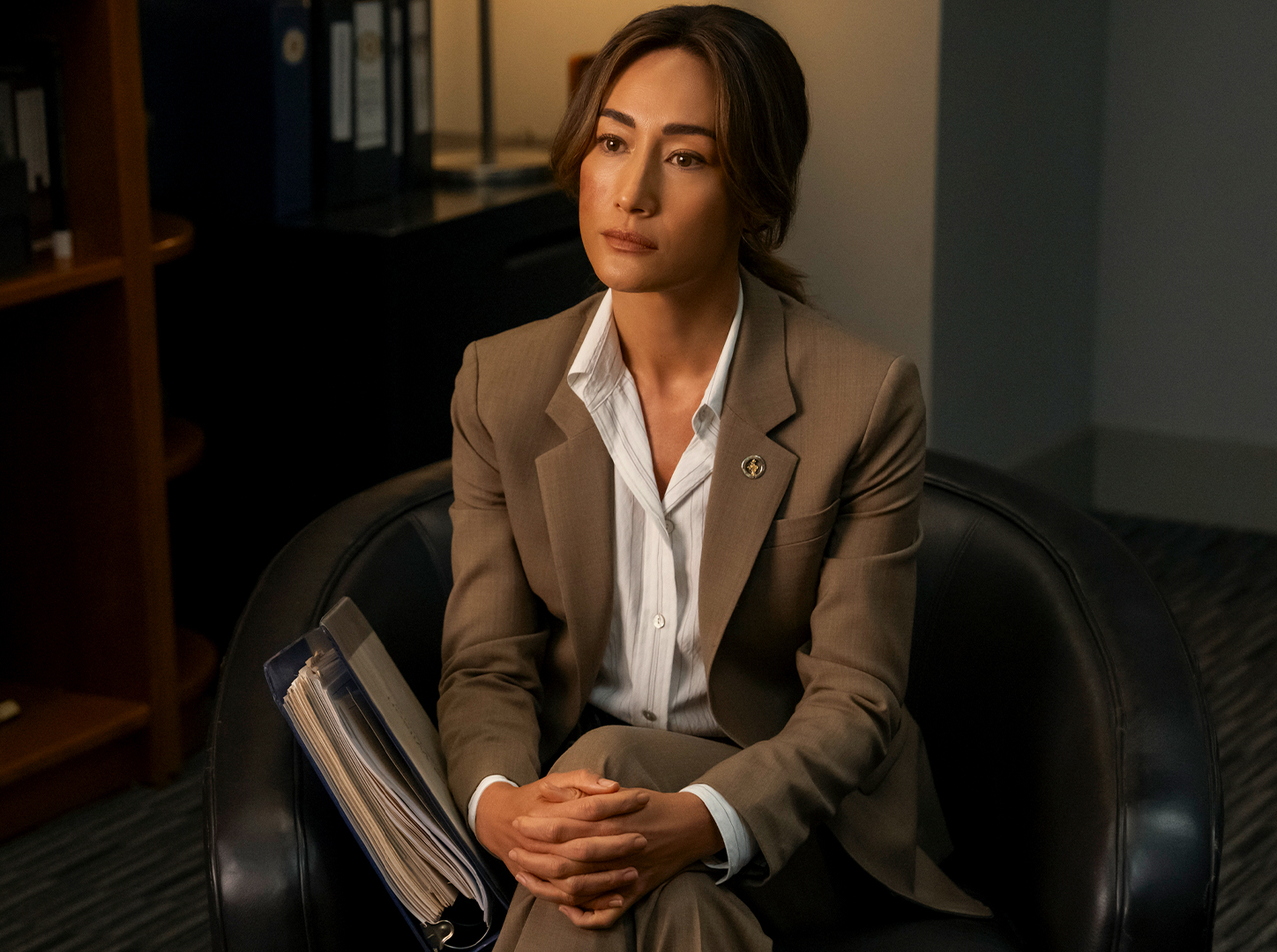

Renée Ballard (Maggie Q) isn’t Harry Bosch in different clothes. She doesn’t sermonise about justice. She doesn’t sip whiskey while listening to jazz records and looking over the city from an apartment on the hills. She doesn’t recklessly run solo gun-toting missions at the bad guys. Instead, she leads a ragtag small team of volunteers and reserves, shoved into a rodent-infested police department basement, painstakingly carrying out the detective grunt work of the cold case unit. They chase crimes the LAPD gave up on, dragging its skeletons into the sun.

Ballard covers several cases over its first 10 episodes that twist and turn as fans will expect, exploring the ugly underbelly of the City of Angels with a sharper, more modern edge than is typical of classic noir. It delves into darkness that’s baked into LA’s sunniest corners, like a college frat house that becomes a crime scene, where carefree party-boy culture hides horrific digital sexual exploitation.

The murder of a gang-involved Korean teen is investigated, as are cases that involve heartlessly persecuted undocumented migrants who are too terrified to talk, a tragic thread tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Black officers wrestling with the realities of serving in an institution that has always preyed on their community. Some storylines burn slow and erupt late; others end early, grimly, and without ceremony.

Despite wallowing in human nastiness, Ballard is also a relentless celebration of Los Angeles, as its predecessors were. Again shot entirely on location, it trades Bosch’s downtown scuzz and Hollywood stomping grounds for a sunbaked sprawl spanning the Westside and the Valley. Bites are had at Rutt’s Hawaiian Café in Mar Vista and Patrick’s Roadhouse on the PCH, while the Lady of the Valley mural in Arleta features as a plot point. Ballard lives with her grandma at Paradise Cove in Malibu, where she blows off steam by surfing, chugging beer and shagging her lifeguard friend-with-benefits.

Even when Ballard isn’t downing cervezas, there’s a boozy reek over everything, a seedy perfume of tequila, 3am burritos and hot asphalt. The beach scenes are beautiful, for sure, but they’re contrasted with grimy places like dive motels where young dreams die behind thin walls and blackout curtains. Despite the sunny exterior, this is unromantic LA noir steeped in cynicism, with a protagonist fighting for justice within a justice system that seems intent on crushing her.

I’d love to write this piece and not mention once that Ballard is female and Bosch is male. I’d love for that difference not to mean anything, and in a lot of ways it doesn’t, because storytelling has matured a lot in how it portrays women onscreen. It’d be nice if gender didn’t matter, but Ballard knows better.

Bosch was driven by the violent misogyny that brutally took his mother’s life, but Ballard is surviving it herself. Hers isn’t inherited trauma; it’s her own, and it’s ongoing. The Brotherhood of the police force has jeered at her, doubted her, abandoned her… and worse. But when they cast her out to the basement expecting her to quit, she stayed, put her head down, and solved the cases they couldn’t.

Institutional rot isn’t just humming in the background. Dirty cops running guns to cartels is one of the season’s core storylines, and Ballard is forced to reckon with it head-on. But she’s no lone crusader against it all. She’s backed by plenty of good men and women who believe in the work just as much as she does. We often see her in leader mode, strategically delegating as her team does the quiet hard yards on the cold cases while navigating the minefield of active corruption.

Then there are Ballard’s own demons. She carries the pain of losing her father in a surfing accident at 14, his body never recovered, sending her down a dark path she never fully returned from. That loss haunts her, as do the more recent betrayals by her former Homicide colleagues. Therapy doesn’t help. Throwing herself into her work with kindred empathy for the closure-seeking families that cold cases leave behind does, or at least buries it temporarily. She’s not driven by revenge, but by tragically unfinished business, and in LA there’s always more of that.

But for all the pleasing ways Ballard carves out her own identity, this show is tethered to its roots. Familiar faces cameo throughout and longtime fans will catch narrative echoes that nod to legacy without leaving newcomers behind. “The past is always present,” is a repeated refrain for Ballard as she pulls old ghosts into the light and lays them to rest while trying to keep her own in the dark. But by season’s end, she better understands that moving forward doesn’t mean letting go of the past, it means learning to carry it properly.

Ballard is the Boschverse embodying that idea: not abandoning its history, not being bogged down in it, but wisely folding it into the new era. Which it has to, because nothing lasts forever. Time gets everyone in the end.