Death by Lightning is a wildly entertaining ride through historical chaos

Netflix’s four-part drama dives into the messy events leading up to the assassination of U.S. President James A Garfield. With excellent performances and a cracking script, this ain’t a dry history lesson.

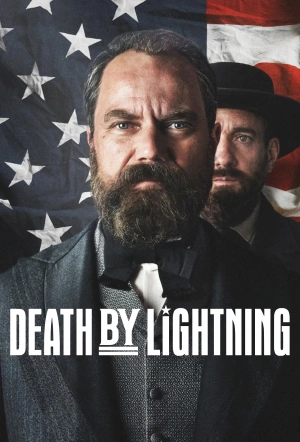

Netflix’s very entertaining political confection Death by Lightning revolves around two key figures: James A. Garfield—the 20th President of the United States—and Charles J. Guiteau, the man who assassinated him. Michael Shannon plays Garfield in the key of “gruff but principled,” a man who believes in public service with every fibre of his being and radiates a moral decency that feels sadly passé—a relic from another time.

Death by Lightning: Limited Series

The juicier role belongs to Matthew Macfadyen, depicting Guiteau as a flaky albeit doggedly determined and remarkably resilient man obsessed with landing a job in Garfield’s administration, later under the delusion that he helped secure Garfield’s rise. The four-part series oscillates between these chalk-and-cheese men, both of whom, we know from the outset, will not receive happy endings. It’s introduced as “a true story about two men the world forgot,” though the very existence of the show suggests otherwise. What that caption really means is: two men who won’t be remembered very well, or very favourably.

Particularly Guiteau. And don’t, by the way, let that French name fool you: despite his ancestry, he was as American as apple pie, pronouncing au revoir with the grace of an Australian sheepshearer (“orr-rev-warr!”). He’s like the titular narrator of Eminem’s Stan: an obsessive, dangerously volatile fan who flips in spectacularly horrendous ways, and takes others down with him.

Our first glimpse of Guiteau isn’t of him, per se, but of his brain in a jar—an employee at a government storage facility during contemporary times wondering aloud, “Who the fuck is Charles Guiteau?” It’s the same question on the mind of creator Mike Makowsky and his screenwriters (adapting Candice Millard’s 2011 book Destiny of the Republic), who jump back to 1880 to paint an outrageous scallywag of a man: bold and impetuous but also well-spoken, ambitious, and pathologically devoted to getting his way—namely, into Garfield’s government, or at least an adjacent space.

Macfadyen cleverly plays Guiteau as more irritating than charming, with the thickest of thick skins. It’s a strange pleasure to watch him get knocked down, then get up again, over and over, whacked around—and bouncing back—like a bobo doll. He’s the sort of guy who hovers outside a door, eavesdropping on a private conversation, then strolls in saying: “I was just walking by and couldn’t help but listen in.” That’s an actual moment, which you expect to lead to a breakthrough for him, but you expect that in many other moments too; this is part of the show’s fun, squirrelly rhythm.

I suspect that considerable liberty has been taken re: historical accuracy. It’s partly for this reason that I hesitated to use the term “historical drama” in the opening line of this article—a manifestly unsexy phrase that doesn’t do justice to the show’s heady energy, nor its appealing tendency to do a Deadwood and mix ye olde-y language (“I lacked purpose, as if a ship without a rudder”) with regular proclamations of “fuck!”

But in broader terms Death by Lightning feels fundamentally truthful in some very interesting ways. It sees history as a strange confluence of constants and chaos: political jiggery-pokery as an evergreen feature of society, but one that rarely unfolds as anyone expects. Garfield’s rise itself was a fluke: he didn’t seek the Republican nomination, became the “compromise candidate” in chaotic circumstances, and narrowly won the general election.

Another compromise candidate was his vice president, Chester A. Arthur—a staunch conservative and, in this show’s view, a real dolt (very enjoyably played by Nick Offerman), more likely to drink too much and have a spew than devise sound policy. And then there’s Guiteau, who, for me, was the real highlight: both infuriating and oddly magnetic. I came away from this series wondering if the world pivots around people like this. That history might be shaped by the competent, and hijacked by the crackpots.