Peter Jackson on the joys, challenges, and surprises in making his latest film

When it was starting to come out the other end restored, I was absolutely stunned.

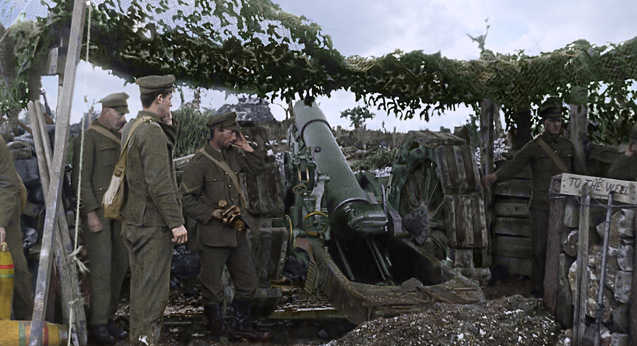

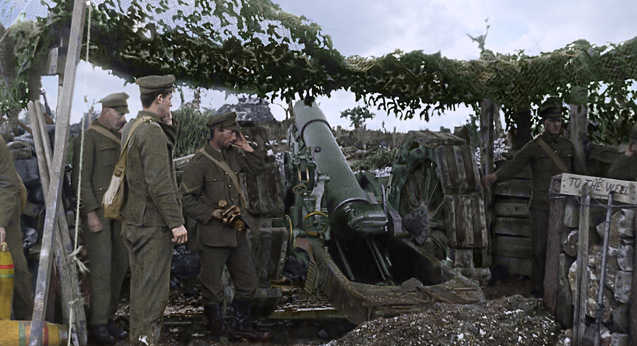

Featuring never-before-seen black-n-white footage that’s been digitally coloured, Sir Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old plays in New Zealand cinemas nationwide November 11 (find times and tickets) to commemorate the centennial of the war’s end.

Liam Maguren, who praised the cinematically caressed experience in his review, talked to Mr. Jackson about making his directorial debut as a feature documentary filmmaker.

Directing a documentary must have been a change of pace for you. Did you have to learn or re-learn any particular skills?

We had a lot of we had a lot of learning and feeling out. What you’re seeing, in terms of restoration, I’ve never done it before. No one I knew had ever done restorations to that degree. So Park Road Post had to write a lot of new software.

It’s like a bit of a puzzle. You look at 100-year-old scratchy film and there’s no “one fix” to it. What you’re looking at is 12 different problems and each problem needs a separate solution. And then there’s the order in which you solve them. Do you fix the scratches before you fix the grain?

A lot of the restoration we were doing was just repairing the damage that occurred in the last 100 years. It’s not what it was when the film was shot, even. It’s been duped three or four times. It’s not even the original camera film anymore. It’s like a copy of a copy of a copy that’s in the archives.

When I first thought about restoring this footage, trying it on three or four minutes of film, I said to them: “I’ve got no idea what the results will be, but let’s try putting computer technology at it.” When it was starting to come out the other end restored, I was absolutely stunned. It was better than I ever thought it would be.

The actual filmmaking process, it was different. My actual favourite part of filmmaking is when I’m in the cutting room. When you shoot a film normally for three or four months, it’s very stressful, you lick your wounds, and you carry on.

When you finally get the shooting finished and you get to the cutting room with all this footage, it’s like: “Well, that wasn’t the film I really wanted to make, but I think we’ve got something OK, so let’s see what we’ve really got.” And that’s what I really enjoy. It’s nice and quiet and it’s just me and my editor Jabez Olssen in the room. I’ve always loved that part of it.

So this time ’round, this was a film made entirely in the cutting room. The only difference is that I didn’t shoot any of the original footage, thank God. It was shot by other people risking their lives 100 years ago. I’ve certainly never made a film where I’ve taken someone else’s footage—100 hours of footage—and make a film from it. That was a new experience for me.

In that 100 hours, there are 10 or 12 feature films in it. We couldn’t possibly put them all in one film. There’s a lot of great stuff with the navy, the nurses, going behind the lines with the women in the factories… These are all stories unto themselves.

We were looking at it all and listening to all the interviews and thinking: “What is our film?” It just came down to the audio material available. It was mainly British soldiers along the Western front.

I found the film to be quite an emotionally rattling experience because, like you, I also had relatives in the war. However, unlike you, I only spent two hours with the film whereas you spent literally hundreds looking at the footage of these men and hearing their voices.

Was it also quite an emotionally rattling experience for you, making the film?

Listening to the interviews, you’re listening to the guys who are in the middle of a 12-hour interview with an audio historian in a quiet room somewhere. It’s fascinating. You could make a film with just one of these guys. It’s such great stuff. But you don’t quite get that emotional feeling from it.

The intensity comes from chopping it all together, bringing an urgency into the editing, adding sound effects, that sort of stuff.

It’s interesting. In 600 hours of interviews, only one guy broke down. I didn’t want to put it in the film because I didn’t want emotion to be put in like that, but Jabez told me: “You’ve got to put that in, mate. I makes me cry.”

It’s fascinating. They’re not quite the victimised people we think they are, these soldiers of the first World War. They were victims, certainly, but they don’t regard themselves as victims, and they’re not asking us to regard them as victims. It’s surprising. That’s the strong feeling that came out of these interviews. These guys were made of strong stuff.