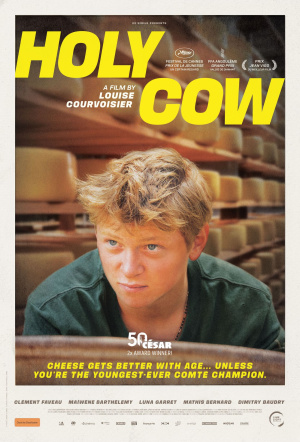

Holy Cow: a coming-of-age drama with a whiff of cheese, and a lot of soul

Cheesemaking meets coming-of-age chaos in this acclaimed French drama full of heart, hormones, and Comté dreams.

A coming-of-age drama, with cheese making as a key part of the protagonist’s cultural background? How very French. But I don’t want to overstate this connection in Holy Cow; I’d heard that the film was associated with the sticky-icky art of coagulating milk, and went in expecting a veritable fromage-fest. That’s not the case. At one point 18-year-old Totone (Clément Faveau), who comes from a family of cheesemakers, learns of a competition to make Comté and decides to give it a go. But this is not a story about saving the farm, or winning a tournament, or succeeding against the odds. It’s not that kind of picture.

Debut director Louise Courvoisier prioritises performances and verisimilitude, surveying the drama through a social realist lens. There are story elements, of course, but no MacGuffins per se, nor a neat three-act structure. Everything relates to character and circumstance. Even what gives the film its edge: the sometimes wild actions of Totone, who we meet as he’s drinking, smoking, and dancing in front of a crowd at a fair. The crowd instruct him via chant to strip naked—and he happily obliges. I’m not sure if there’s any narrative significance to this beyond establishing that Totone is no shrinking violet.

He lives in the picturesque Jura region in eastern France (famous for its Comté) with his seven-year-old sister Claire (Luna Garret) and their father, who we barely meet before he’s whisked off the mortal coil. Totone is hot-headed and impetuous, but adapts to changing circumstances and steps up in his care for Claire, and shows some initiative vocationally—including through the aforementioned competition, which offers a juicy €30,000 prize.

It doesn’t take long for Clément Faveau to really resonate in the lead role: it’s an expressive but restrained, thoroughly convincing, multi-dimensional performance. You want this guy to sort himself out, perhaps even want the best for him—but you might also be a bit wary of him; he’s got a dangerous streak.

Deep into the runtime, which is a lean but full-feeling 90 minutes, it struck me that despite Totone being a fully developed character, I didn’t really understand him, didn’t know who he was. Almost certainly he’d feel the same way. He’s at an age of self-discovery, the passing of his father marking a very clear crossing point—perhaps by necessity more than anything else—into adulthood.

As is common in social realism, story elements are introduced but not necessarily resolved, reflecting that realist and just plain true view of the world—as a place that rarely offers finite resolutions. Nor do things neatly “begin.” We see this in the relationship between Totone and dairy farmer Marie-Lise (Maiwene Barthelemy), which just sort of happens. They come together sexually, and potentially romantically, in ways that feel organic, almost unscripted, and mostly lust-related, with unfulfilling bedroom encounters that nevertheless leave the door open for something greater to grow. The conventional term “love interest” feels too reductive; too neat for the film’s scruffy edges.

In the background, there’s cheesemaking. It’s part of life in this neck of the woods, so it stands to reason that Totone might develop his skills if he sees something in it for him. The film very genuinely depicts how people often become ingrained in particular professions—not because they’re“called” to do so, or amazingly gifted, or that the stars aligned, as the movies have a habit of telling us. An opportunity arose; they took it; one thing led to another. Which sounds a little matter-of-fact, but Holy Cow is not without a sense of romanticism—albeit of an earthy, hands-in-the-soil kind. Or perhaps that should be: hands in the stinky, sticky, gooey, cheesy mess.