How 2022’s regency-inspired romances are shaking up Jane Austen

Persuasion, Fire Island, and Mr Malcolm’s List all reinvigorate Austen, with mixed yet fascinating results.

Three very different takes on Jane Austen’s witty literature have appeared on our screens this year. Rory Doherty assesses how each of them tries—and often succeeds—to make the 19th century prose feel fresh as ever.

By this stage, there isn’t a country manor in Britain that hasn’t been the setting for a filmed version of Jane Austen’s work. That doesn’t cover all the adaptations set in the modern era, or works that were inspired by her body of work of only six novels. On the small screen, Austen’s influence stretches on in Netflix’s Bridgerton and ITV’s Sanditon, where stories are penned beyond her words, boldly wearing her legacy.

But in film, a common thread runs through three, Austen-adjacent 2022 works: an attempt at modernisation, where the voice and style with which Austen’s stories are told is altered. Fire Island, Persuasion, and Mr Malcolm’s List all illustrate how filmmakers think audiences can respond to her novels with varying, unique contexts and approaches.

On the surface, you wouldn’t expect Fire Island to contain all the subtle asides and entrenched patriarchal dynamics that characterise Austen’s work. The film transplants Pride and Prejudice’s story of sisters seeking marital stability to a diverse group of gay men who make an annual pilgrimage to a gay holiday island. Here, Austen is used as a framework; writer/star Joel Kim Booster and director Andrew Ahn tell a story of queer Asian-American characters, and how prejudices and pressures still dominate their lives somewhere that’s meant to be a safe haven.

Despite using a 200-plus year narrative as its structure, Fire Island has an authentic, independent identity, capturing both the joys of a queer community and the lows of having your body, personality, or class criticised within that community. “Jane Austen’s observations about how human beings judge each other really gets to the core of how we are as [people],” director Andrew Ahn says. “And about how we can break through some of that judgement to create true and authentic connection.”

All the derisive asides and entrenched hierarchies are still present, they’re just being commented on from a different perspective. Booster and Ahn adeptly tell a story that’s uniquely theirs, while paying homage to the astute voice of a revered satirist.

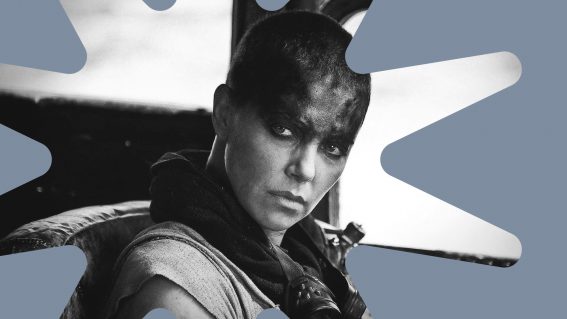

A less adept modernisation of Austen risks losing any such distinct voice, such as Netflix’s Persuasion starring Dakota Johnson (an actor, it has been argued, is too modern for such a period setting). The film has been derided by Austen fans for its lack of faith to the author’s text. The rich emotional descriptions, where characters struggle to articulate their pain with words alone, have been largely replaced with peppy, snappy asides, references to exes and empaths, and Johnson’s Anne Elliot casting frequent glances to the camera.

At least when shows like Fleabag or Gentleman Jack employed fourth-wall-breaks, they were shows with concrete identities; one of Persuasion’s fatal flaws is its lacking in any personality, when it adapts an author who had nothing but.

Instead of staging Persuasion’s rich tale of regret, director Carrie Cracknell and writers Ron Bass and Alice Victoria Winslow have chosen to facilely modernise their story with anachronisms that reveal nothing about the ways in which a classic story can connect with a contemporary audience. It’s patronising in a way; the Netflix audience is not seen as discerning enough to appreciate Austen’s text for what it is, when a glance at her prolific influence on our current media landscape (and the legacy of iconic adaptations) proves just the opposite.

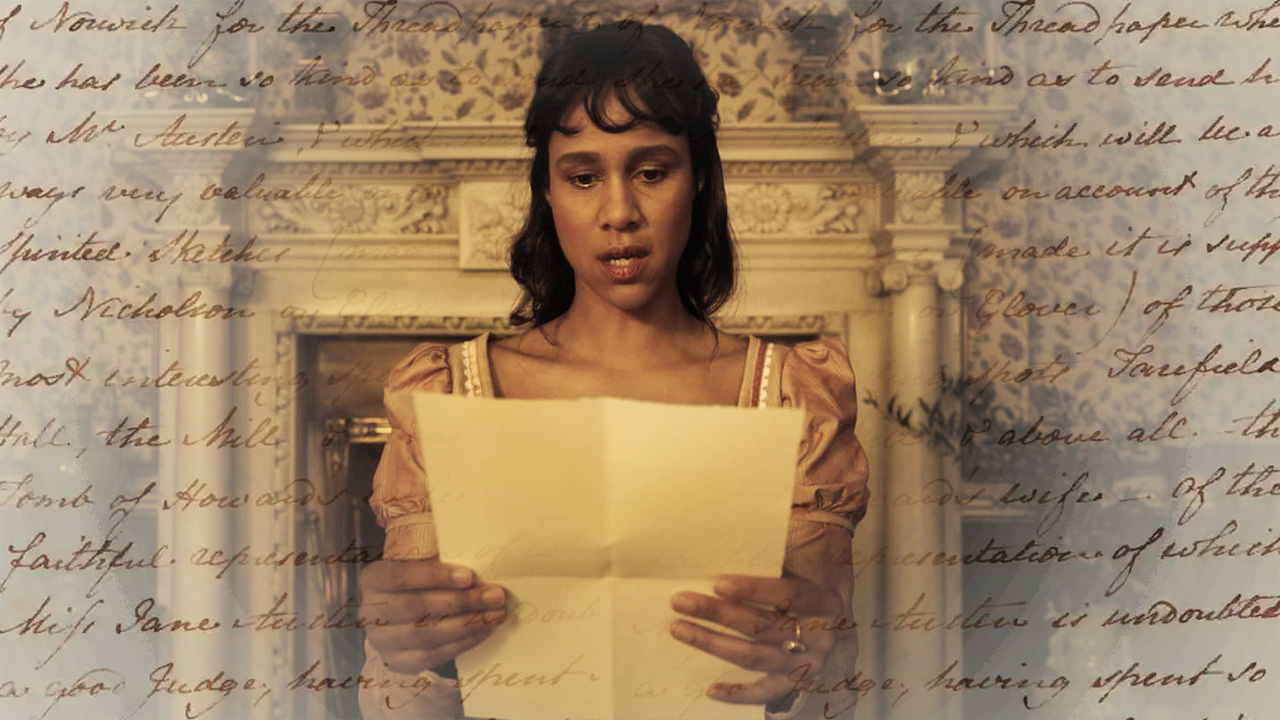

Mr Malcolm’s List, by contrast, doesn’t do anything revolutionary with the archetypal Regency comedy—although it does update the casting, with a refreshingly diverse ensemble in contrast to the typically all-white Austen adaptations that have come before.

But the film doesn’t adapt one of Austen’s stories, rather American screenwriter Suzanne Allain’s own self-published book that follows the tradition of Austen and other British historical satirists, like Georgette Heyer or P.G. Wodehouse. But being written in the 21st century doesn’t mean Mr Malcolm’s List has dressed up the story with contemporary dialogue: rather, it acknowledges parallels between our times and Regency society.

The titular Mr Malcolm has a sizeable fortune, and is being selective of who he courts with a list of desirable attributes a bride should have. It’s a concept that feels overly formal and antiquated, appropriate for a Regency-era comedy, but is it really so different from the misogynist qualifications today’s men use in deciding in dismissing women in dating, rating them numerically and viewing their worth only through the lens of their own standards? Such an angle gives resonance to Allain’s story, just as Austen’s legacy was made richer by Fire Island’s overlaying different contexts on her writing.

With films like these being produced, the relevancy of her biting, romantic stories can never be in doubt.