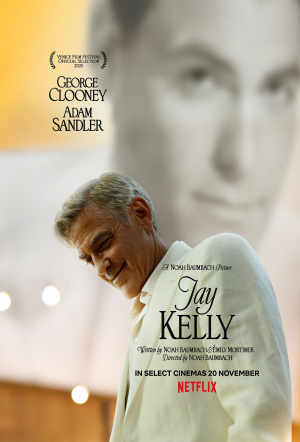

Jay Kelly celebrates actors playing into their star persona

George Clooney plays a movie star in Jay Kelly – a sly, slick vibe check on those who fear their celebrity is ossifying and their personal lives are crumbling.

George Clooney’s two most recent starring roles both leaned heavily on his celebrated chemistry with not one, but two of his Ocean’s Eleven co-stars: Ticket to Paradise with Julia Roberts and Wolfs with Brad Pitt. Neither film amazed; after years of shifting between smooth-talking criminals, bug-eyed buffoons, and embittered pros losing their edge, Clooney’s recent performances were the definition of coasting, more in-keeping with his Nespresso commercials than the films that first cemented him as the platonic ideal of a modern movie star.

Clooney has been busy with calling out politicians both on Broadway and in real life, but with Noah Baumbach’s Sad Celebrity drama Jay Kelly, the A-lister enjoys his meatiest and most promising role in a while—while simultaneously marking out the outer limits of his dramatic comfort zone. Jay Kelly (Clooney) is a Hollywood star increasingly consumed with anxiety and doubt. It’s the summer before his daughter Daisy (Grace Edwards) goes to college, and she’s travelling instead of spending two weeks with him in between projects. After a couple mishaps in LA, Jay flees to Europe to be honoured at a Tuscan film festival—and surprise Daisy while she’s interrailing—rather than face bad press, another tired shoot, and reminders of his own inadequacies back in Hollywood.

With supporting roles for Adam Sandler, Laura Dern, Billy Crudup, Patrick Wilson, Emily Mortimer (who co-wrote the film with Baumbach) and Gerwig, Jay Kelly is a sly, slick vibe check on those who fear their celebrity is ossifying and their personal lives are crumbling—Kelly feels taunted by his heroic, kind, winning movie characters.

Clooney has clarified he’s glad he never lived Jay Kelly’s “life of regret”, but in an awards season that also features Dwayne Johnson playing a hulking athlete with debilitating frailty, it feels like A-listers are deliberately courting Oscar buzz by playing characters who hold up a distorted mirror to their own career. It’s a strategy that two of Clooney’s “last movie star” contemporaries have opted for in recent years: Brad Pitt played silent cinema star Jack Conrad in Babylon, Damien Chazelle’s elegy to those lost as Old Hollywood regenerated itself; Leonardo DiCaprio played the washed-up, crybaby action hero Rick Dalton in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which focused on B-pictures and Western TV as Hollywood found itself in a post-studio system, small-screen boom.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Babylon

Conrad and Dalton worked in an industry decades older than Kelly did (Conrad’s heyday was a century ago), but the ways that these mega-stars step into fragile, messy characters feel notably similar. All three actors (that is, the real actors, not the fake ones) have seen firsthand how their stardom has opened doors and been treated as a commodity. When directors offer them a chance to lean into that not-quite-authentic identity and prove that actually, they can be in on the joke and deliver an antidote of pathos, they leap at the chance—not just for the freedom it offers, but because it implicitly services their brand.

The historical contexts of Jack Conrad and Rick Dalton distinguish them from being exact clones of Pitt and DiCaprio; we can perhaps say that they represent what men of Pitt and DiCaprio’s talent would succeed and struggle with in different moments of film history. Jay Kelly, down to the tribute video that the Tuscan film festival uses to honour the actor, is daring you to project Clooney’s persona and career onto the character’s. This situates Jay Kelly closer to Birdman, where Michael Keaton played an extremely neurotic washed-up star who once played a winged, animal-themed superhero, now cloying for prestige on Broadway. The story is built out of this winking casting choice, and even though Riggan’s personality feels singularly self-destructive, it’s not like his career is totally dissimilar from Clooney’s.

In a supporting role, Clooney pastiched an airhead leading man in the Coen Brothers’ Hail, Caesar! There, he was Baird Whitlock, the leading man in a Biblical epic and the centrepiece for the Coens’ satire of Hollywood’s flattening of high and low culture, especially when kidnapped by blacklisted communist screenwriters (becoming a quick convert). It calls to mind the motley crew in Tropic Thunder who are plunged into the real Golden Triangle while filming a war movie. The pastiches are drawn from the same bickering, neurotic self-criticism in prestigious auteur projects about star persona, but basically every character in Ben Stiller’s comedy is a caricature of a “Hollywood type” that exists to be humiliated.

Lost in Translation

Somewhere

Sofia Coppola has built two films from shrewdly casting a celebrity as an imagined double looking for warmth in a cold, sheltered, and luxurious world, and they are as melancholic as Tropic Thunder is broad. Most memorable is Bill Murray as Bob Harris in Lost in Translation, isolated in Tokyo to film a whiskey ad and, like Jay Kelly, estranged from his loved ones. But as troubled hotshot Johnny Marco, Stephen Dorff lends Somewhere an equal amount of humbled, wounded authenticity. No doubt Coppola’s explorations of estrangement and redemptive love (but not her restrained, chic naturalistic style) inspired Jay Kelly’s determined search for himself in the faces of admirers, employees, relatives, and his own characters.

Clooney’s ability to be sharp, severe, and funny is underlined by sensitivity and vulnerability, and it puts him in conversation with the richest examples of over-the-hill actors confronting their fragile legacy—like Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight, where he faces his personal strife and declining career through the persona of a faded vaudeville star, or Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets, starring Boris Karloff as a crotchety, almost-retired B-horror star as New Hollywood and a reckoning with American violence approaches.

But the most interesting wrinkle in this tradition of actors poking fun at cases of “lifelong actor brain” is its clear gender split—movies starring Clooney, Pitt, DiCaprio, and Murray aim for a poignant, almost mournful melancholy surrounding faded men that ignores more slippery questions of losing your identity and sanity. Although films like Sunset Boulevard, All About Eve, or Opening Night were written and directed by men, the thorny, ugly exploration of desperation and loneliness combined with the canny casting of Gloria Swanson, Bette Davis and Gena Rowlands gives us films of real heft and fear that survive any easy comparisons between real actor and on-screen persona. That is to say, as sparky and winning as George Clooney’s performance feels, until Jay Kelly experiences his own Mulholland Drive ego death, it feels like this savvy, winking strain of meta-casting has more to give.