Apocalypse, maybe: how end-of-the world movies have changed

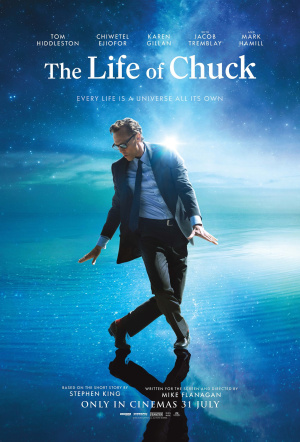

The Life of Chuck is the latest in a suite of recent movies that view the end of the world from an oddly aloof perspective. Armageddon isn’t what it used to be.

The end of the world isn’t what it used to be. Once upon a time movies delivered good old-fashioned apocalyptic carnage: asteroids, alien invasions, new ice ages, and other cataclysmic events that could decisively conclude this silly thing we call human existence. Recently filmmakers have become more circumspect in their contemplation of the collapse of everything—often viewing the end of times from a distance, or off to the side, as if it were just another burst of white noise in a terribly loud universe.

Take, for instance, The Life of Chuck, adapted from a 2020 Stephen King novella. It begins with school teacher Marty (Chiwetel Ejiofor) in a classroom, when news breaks of an earthquake so massive it takes out the internet. This is one in a series of world-altering events that occur somewhere else, off-frame. We learn that people are evacuating California; people are evacuating everywhere. In the words of one character: “This is the end of everything.”

What caused it? There’s no asteroid, no aliens, no extreme weather events, no zombies. The fallout seems pretty peaceful too: I didn’t even spot one measly gang of Mad Maxian marauders. In fact the tone is pensive and misty-eyed. In another scene, before the film jumps back in time to introduce the titular character (Tom Hiddleston) and explain his connection to the cosmic scheme of things, Marty and his ex-wife Felicia (Karen Gillan) calmly observe a blue and pink night-time sky, as planets literally start disappearing.

“There goes Mars,” Marty says, as if this were a daily occurrence. Anybody who watches The Life of Chuck for its end-of-the-world elements will be disappointed; we don’t even see news footage of society going to the dogs.

There’s a little more of that in Mountainhead, another film released this year that’s sort of, maybe, about the end of the world, but not in the Roland Emmerich way. The tone is very different: it’s a stinging satire from Succession creator Jesse Armstrong, set in an absurdly opulent modern abode in the mountains of Utah, where a bunch of Silicon Valley billionaires (Steve Carell, Cory Michael Smith, Ramy Youssef and Jason Schwartzman) gather for a poker weekend.

It becomes clear that a global crisis is unfolding that’s at least partly their fault, resulting from the rollout of powerful deepfake tools. Populations are revolting, cities are burning, global order is collapsing. But again the real bedlam is elsewhere, away from sight. We remain in the billionaire’s hideout, listening to these filthy rich tech bros chew the fat. In other movies these characters could’ve been Bond villains, delivering “here’s my evil plan” monologues in ice lairs.

Mountainhead takes a different path—suggesting villainy is subjective, rooted in hubris, ambition, dangerous technology, and hypercapitalism. And that real villains often deny they’re doing anything wrong. Cory Michael Smith’s character, Venis, who is the CEO of the company that rolled out the dangerous new tech, skeptically looks at evidence of what’s happening in the wider world and wonders whether it’s real. “Heads don’t explode like that,” he says, responding to one video. This reflects a contemporary distrust of audio/visual information; a feeling we can no longer trust our eyes and ears.

That anxiety was cleverly integrated into M. Night Shyamalan’s Knock at the Cabin, which turns a “holiday from hell” narrative into an “apocalypse, maybe” narrative. Married couple Andrew (Ben Aldridge) and Eric (Jonathan Groff) are vacationing with their daughter (Kristen Cui) in a remote cabin when a group of weirdos arrive, tie them to chairs, and claim the world will end if they don’t offer up a human sacrifice. Leonard (Dave Bautista) insists that “cities will drown” and “the sky will fall and crash to the earth like pieces of glass.”

Leonard turns on the TV to try and prove his predictions are coming true, news bulletins reporting events such as megatsunamis and the outbreak of a deadly new virus. But Andrew questions the veracity of the footage, suggesting they’re using pre-recorded segments in an attempt to fool them. As I wrote in my piece about the film, Knock at the Cabin is less about the end of the world per se than the collapse of consensus reality. Shyamalan taps into the “philosophically rubbery nature of existence while evoking a message that maybe, just maybe, the crazy person is right.”

Technology and media representations are also an important part of Leave the World Behind, another film involving vacationing people whose leisure time is rudely interrupted by the apocalypse. Married couple Amanda (Julia Roberts) and Clay (Ethan Hawke) go to a swanky rental house with their kids for a weekend away when odd things start happening.

First, they lose TV and wi-fi signals; weird, but no biggie. Then an oil tanker crashes into the beach they’re flopping around on. Deer start acting funny, the television switches to an emergency broadcast signal, and a couple of strangers (Mahershala Ali and Myha’la) arrive on their doorstep, asking to stay.

As the runtime progresses, a thick sense of mystery remains. That mystery involves—like in the other films mentioned above—not just what’s appearing but why we’re not being shown it. Perhaps we’ve seen the end of the world so many times, so we crave something different. Perhaps we’re currently experiencing the early stages of armageddon ourselves, and don’t want to admit it. Or maybe Roland Emmerich is too busy and not returning Hollywood’s phone calls.