Retrospective: revisiting the lovely, life-affirming pleasures of Amélie

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s sugary rom-com is especially tasty in the wake of social distancing and a culture obsessed with nostalgia.

Released in 2001, Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s delightful Amélie is still a winning reminder to find romance in one’s daily life. Eliza Janssen revisits the film on its 20th birthday, finding that time spent in lockdown has only made its message sweeter.

Amélie is literally the first film atop the search results for “whimsical movies.” Alongside Disney musicals and Tim Burton’s schmaltziest efforts, you’d be excused for remembering the 2001 French comedy as an exercise in sentimental style over substance.

And you would be right: drenched in the unrealness of green and the romantic warmth of red, Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s fourth feature is a painstakingly curated collection of sweet moments. The awful Miramax trailer below shows off the worst of Amélie‘s perceived appeal (were the Weinsteins worried that audiences would clock this as a foreign-language film??), exhibiting only kooky faces, CGI dream sequences and frenetic glimpses of pure. Uncut. Whimsy.

But, in the paraphrased words of Brenda Lee, isn’t that all there is? In this defensive spirit we celebrate the 20th anniversary of Amélie, as an enduringly lovely film that uplifts life’s little pleasures as the very meaning of life itself. In fact, Jeunet’s focus on the small stuff feels (sorry) More Important Than Ever: just check out the very un-COVID-friendly nature of our protagonist’s favourite human experiences.

Dipping one’s hand in a sack of beans. Silent kisses applied to a stranger’s face and neck. Turning in a crowded cinema to watch the audience’s faces as they react. The very choice of intimate, sensory pleasures all seem to speak to our hygiene-focused, distanced state. Or maybe that’s just me, drawing from my recent experiences coming out of hotel quarantine.

Trapped somewhere between spontaneity and rigid order throughout 2021, without finding any joy in either of those extremes, all the small things really did make life worth living: Blink 182 was right. When you can only go for one stupid little mental health walk per day, and line up for your stupid little overpriced coffee? Or worse, do nothing but watch a visiting bird at your stupid little window that doesn’t open?

They stop feeling quite so stupid and little after a week or 11. Recently I’ve felt the boundaries of daily life shrink to close in around me, making the whimsical and trivial feel much more substantial than I’d like.

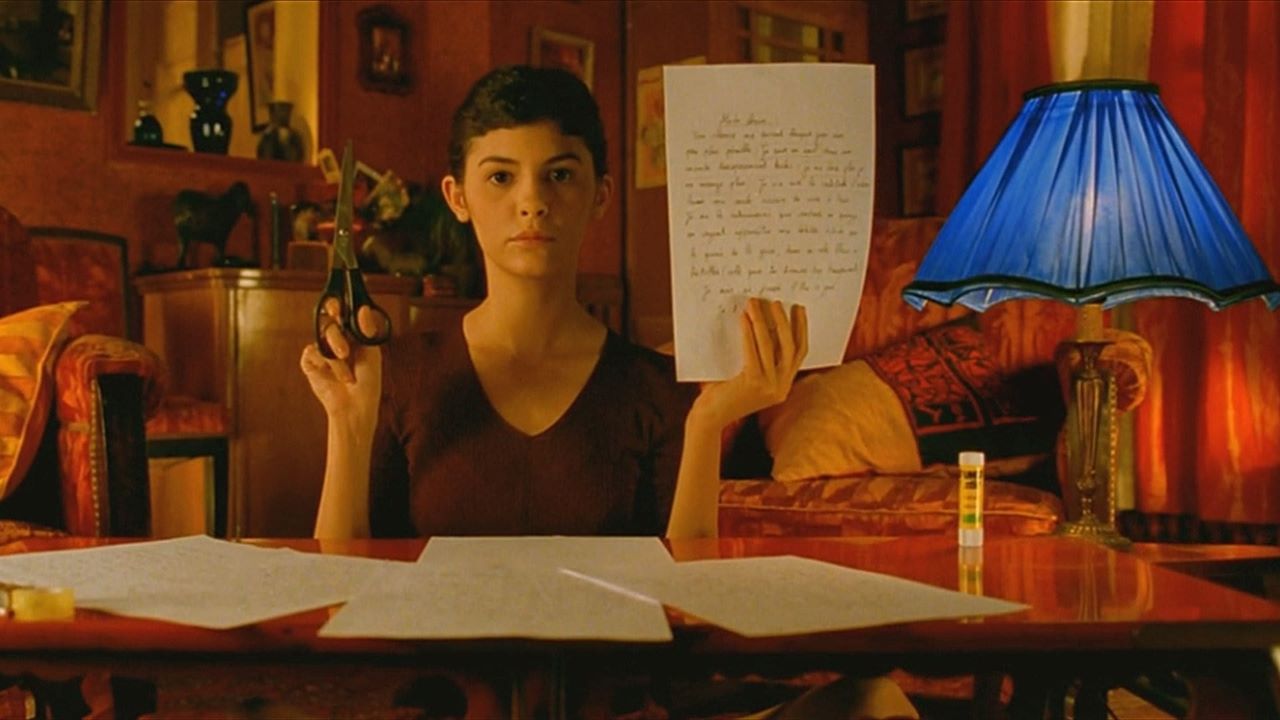

Audrey Tatou’s titular waitress isn’t quite a Manic Pixie Dream Girl, despite that iconic pixie cut. Unlike the waifish love interests who better suit that term, Amélie is painfully aware that her life revolves around helping others find meaning. The film begins with one angelic act of kindness and devolves into obsession, visions of martyrdom and a lavish state funeral; she’s unable to stop herself from setting up one cutesy obstacle after another to keep crush Nino (Matthieu Kassovitz) safely at arm’s length.

Tatou manages a soufflé-light balance between introversion and longing. In a world of adults that act like overgrown children, she’s just one of the quietest, steamrolled by obnoxious co-workers and foes. Because of her shyness, however, Amélie is able to exert a magical realist control over the world that vexes everybody else. Jeunet’s camera will often pause in its movements to track Amélie as she bends to pick up a perfectly skippable stone.

Whimsy is often seen as empty or superficial at best: at worst, it can be downright cloying. I’m not irritated by Amélie but on rewatch only a couple of the characterisations hold any true, poignant dimension.

Both involve old men rediscovering themselves through Amélie’s romanticising eye. Her Manic Pixie Brittle-Boned Housebound Neighbour (not such a popular trope for some reason) is constantly trying and failing to capture the essence of the most inscrutable character in a Renoir painting. And her apartment’s former resident is shaken when reunited with a childhood collection of seemingly insignificant souvenirs.

“To a kid, time always drags”, he tearfully realises. “Suddenly you’re fifty. All that’s left of your childhood fits in a rusty little box.”

It’s only through art and scrappy, nostalgic bric-a-brac that any of the characters in Amélie ever manage to connect. Amélie and Nino’s love language is twee scrapbooking and anonymous photocopies; she invigorates her father with Polaroids of his beloved garden gnome travelling the world. As the world is cautiously opening back up and Amélie turns 20, I hope we don’t lose sight of our own rusty little boxes. That desire to record the acute, miniature, and beautiful pleasures within our 5km radii.

Whimsy is basically all we have and, through Amélie’s rose-and-green-coloured-glasses, romanticising one’s own life is admired as a worthwhile mission. “We all need a way to relax”, explains the film’s former Metro inspector, who now punches holes into laurel leaves instead of tickets: “such is life!”