Robinson vs Rudd: Two different kinds of comic “normality” collide in Friendship

Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson have always mined normality in their comedy – here ‘funny and relatable’ meets ‘reluctantly, shamefully recognisable’.

It is hard to make friends as an adult. Trying to speedrun closeness with strangers is an anxiety-inducing process, and this deeply intimate social cringe is the weapon of choice for Andrew DeYoung’s Friendship, which diagnoses the “male loneliness epidemic” as a product of grown men wrestling with social dysfunction and an overinvestment in male friendships that will make them spiral out of control.

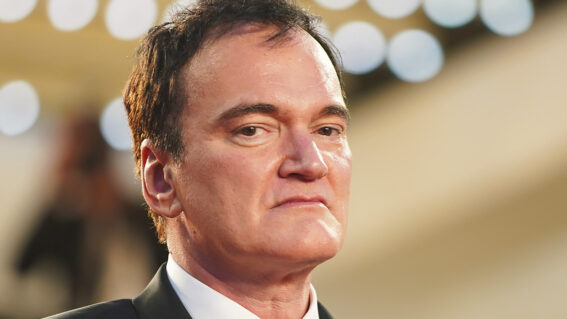

That’s par for the course for actor Tim Robinson, who plays Craig, a socially awkward and unlikeable suburban dad. His wife Tami (Kate Mara) has recently recovered from cancer and is far closer with their son Steven (Jack Dylan Glazer) and her off-screen ex Devon (Josh Segarra) than her dead weight, emotionally useless husband.

Since his breakout Netflix sketch series I Think You Should Leave, Robinson has carved out a niche of playing characters who tank the mood at dinner, at work, at parties because they don’t know how to act otherwise. Robinson observes a lot of real insecurities and hang-ups that plague people with short fuses, and he pushes their outbursts to obscene levels of entitlement and aggression. The skits are funny, but also humiliating—part of us is relieved that we are spared further cringe when they wrap up after 5 minutes.

Related reading:

* Are triples best? Tim Robinson is back with I Think You Should Leave

* Everybody’s Live With John Mulaney makes other TV look so freaking safe

* Mountainhead delivers ice-cold billionaire satire

Friendship denies us this relief, drawing out the lifespan of a I Think You Should Leave character to feature length, confronting him with his own self-sabotaging psyche in the process. Even though Craig feels the space growing between him and his wife, he decides the way forward is to befriend his neighbour Austin (Paul Rudd), a cool and charming weatherman who is genial enough to let Craig into his inner circle—at least, until Craig drops enough lethal faux pas to sour Austin on him.

Robinson’s comedy is hilarious and cringe-inducing for the same reasons—it’s grown from the seed of real social gaffes. Think of the man who refuses to skip his lunch for a meeting, the man dressed as a hot dog passing the blame for crashing a hot dog car, or the Love Island contestant who was called out for hogging the zip line.

Realising you have eyes on you and you have to field questions about your poor behaviour is a feeling that makes all our collective skin crawl. But when Robinson’s characters refuse to admit they’re in the wrong, double-down when challenged, and get so catastrophically hung up on immaterial social rules, we get a glimpse into a terrifying alternative reality where we could react to anxiety by losing all semblance of common sense and emotional regulation. It’s heightened cringe, but it’s also grounded in something real—and Friendship’s Craig features the same pitiability throughout.

Friendship extracts a lot of strangeness and dread from its seemingly normal dramatic premise, but the dark comedy is so compelling because Robinson and Rudd have spent their careers mining “normality” for their specific strain of comedy. But while Robinson takes a recognisable social dysfunction and balloons it up to oversized heights, Rudd has smuggled his humour into down-to-earth everymen, leaning on his handsome Hollywood charm to distract us from how sharp and disarming a comedian he is.

Friendship works because it understands that these actors often play characters with contradictory relationships to normality, and putting them side-by-side reveals why the “movie comedy everyman” wields so much more control than Robinson’s brand of spiraling loser.

In I Love You, Man, Paul Rudd plays a nice, normal, engaged man who has no actual male friends, and is the ultimate straight man to the oafish stoner played by Jason Segel who is parachuted in to be The Ultimate Male Friend. Rudd isn’t just there to amplify Segel’s wacky, off-colour jokes, he’s also an audience surrogate for everyone who secretly wants a 2000s bro-comedy lead for a best friend.

In his brief stint on the megasuccessful Friends, Rudd signed up as Mike, the love interest of the eccentric Phoebe (Lisa Kudrow)—Mike was funny, empathetic, observant, and an exceedingly normal man dropped in to ensure that Phoebe was happily married by the end of the series. If Rudd is funny in his everyman roles—even as Ant-Man among a fleet of quippy, intergalactic and super-serum’d Avengers—it’s usually with realistic awkwardness or jokey dialogue that never sacrifices his ordinariness.

In his greatest role, the rom-com parody They Came Together, Rudd pastiches the average rom-com male lead by overacting all the expected and sincere beats of the story, underlining how constructed these characters really are without breaking from the structure of the genre.

Friendship weaponises Rudd’s normal-funny vibe by making his character—a cool guy whose coolness is limited to having friends, being in an amateur band, and being a junior weather reporter at the local news station—the ultimate object of envy for Craig. Craig’s inability to control himself socially puts Austin on a pedestal; we only observe this genial, friendly suburban husband through the shimmering lens of Craig’s desire.

Taking the dynamic we’re most familiar with in a studio comedy—a dorky but genuinely winning everyman in the lead, with an absurd and often grating character as a supporting player—Friendship flips them. Paul Rudd and Tim Robinson have always mined normality in their comedy, but Friendship breaks open how different their purposes have been. Rudd can be funny and relatable in a way we’re comfortable with, even aspire to. Robinson is funny in a way that we reluctantly, shamefully recognise. Rudd’s characters are normal because he’s been designed that way; Robinson’s characters are real because they’d be hopeless at being an “everyman”.