The Low-Budget Mentality

As my esteemed colleague Liam “Man Of 100 Words” Maguren has probably brought to your attention, I currently have a film project which is battling it out in the final public voting rounds of the MAKE MY MOVIE Competition.

My film is one of 12 projects duking it out for a shot to receive a $100,000NZD budget to turn our ideas into actual movies. A $100K is a lot of money if you’re measuring it in terms of what you can buy for, say, personal property or consumer products or a vacation around the world or gifts for your friends and loved ones. A $100K is also NOT a lot of money when you’re trying to do something like make a movie. In reflection of this curious dichotomy, I thought perhaps this week it’d be good to ponder the strange concept that is the, so-called, “low-budget movie”.

Movies cost a lot of money to make. There is no other way of saying or phrasing this. There are no other interpretations, though many people will argue till they’re blue in the face that this is absolutely untrue. Why? Because of this, rather simplistic I admit, set of rules:

And why do movies require so much time and energy? Because movies are about recreating reality. You can’t film reality because reality is a) an ugly and undefined mess most of the time (which is what makes documentaries so interesting) and b) often mundane and never looks as exciting or dramatic or sexy or interesting as a movie does.

Take this scene from Christopher Nolan’s famous, running-backwards, film Memento where Guy Pierce plays a man who can only form short term memories that fade after a few minutes and has to constantly write notes to remind himself of people he’s met and places he’s been. In this scene, which is an argument set in a seemingly mundane house, Carrie-Ann Moss’s character is about to manipulate our hero by goading him into striking her, then leaving the house for a short time so his memory will reset…

Everything seems pretty mundane and deceptively cheap to the untrained eye: two actors yelling at each other in a living room. One of them leaves to sit in the car and then returns moments later. You’d think that a scene like that would cost nothing at all…and you’d be totally mistaken.

Let’s start with the camera – your home movie camera can’t record images sharp enough to compare with the way the scene looks in Memento. Not even DSLR’s with video features can do the job unless it’s wielded by a true professional and even then trained eyes can tell the difference at a simple glance. Real movie cameras (or cameras good enough to shoot A movie of some sort on) are dedicated pieces of extremely high-tech equipment and, naturally, such pieces of equipment cost a lot of money. And because this gear costs a lot of money, scenes like the one above are usually shot with ONE camera…which means that every time movie cuts between Guy Pierce and Carrie-Ann Moss, we’re seeing a different take shot by turning the camera around and facing the OTHER way. So for every shot you see in this little scene, the entire scene was shot again and again and again in order to get all the different angles. This takes a lot of time and, as we already know, time can cost a lot of money.

Your typical, everyday, run-of-the-mill, people-who-make-movie-cameras-go crew.

They also require specially trained people who know how to operate them: usually an operator who, through beautiful hand-eye coordination, can line up nice looking shots, a focus-puller who makes sure that the image is always in focus (it’s very hard to operate a camera AND run the focus during a moving scene) and a camera-assistant who ensures that the camera is running efficiently, smoothly and without problems so that the operator and focus puller can get on with their jobs. This also requires a lot of money.

Then there’s the lighting: your eye sees far greater shades of light and dark, simultaneously, than any camera in the world because your vision is constructed inside your brain through information gathered by the cells in your eyes. Your brain creates the world you see and seamlessly mixes light and dark without a problem. Cameras can’t do that and even if they could, real life doesn’t look so ‘dramatic’ in terms of lighting all the time. So you have to make the scene look dramatic with light. A LOT of light. In every, single, shot you see in the above sequence there are anywhere from 5-15 different lights on stands and on the floor, just out of shot, lighting up the actors, the walls, the windows, the ornaments and props you see in the background. Everything in the scene has its own tailor made light source, deliberately put there to make the scene feel ‘natural’, but look ‘dramatic’. The lights are delivered to filming locations on big trucks and setup by teams of 5 to 10 burly individuals under the direction of a gaffer (lighting designer) and cinematographer (whom the lighting designer reports to). This is all specialized gear and highly trained people. And this costs a lot of money.

Now look at the clip again from 0:14 – 0:22. Notice the way the camera slowly moves closer to Guy Pierce as Carrie-Ann Moss circles and taunts him? Cameras are heavy and humans can’t move cameras smoothly just be walking so the camera is mounted on a specialized piece of gear that creates smooth movements such as a dolly or a steadicam. Dollies are large, unwieldy, metal cars that run on rails which need 2-3 people to setup and a couple of people to push back and forth in synchronized movements with the acting. Steadicams are heavy gyroscopic rigs worn by a camera operator that smooths out the bumps of human footsteps and also require a couple of people to setup, operate and run. These are all specialized pieces of hi-tech gear. And so they cost a lot of money.

The generators that run all the power that these lights and cameras and playback monitors feed off? They cost money. The people who transport, fuel up and run the generators? They cost money. The portaloos that these crew members use (especially if they’re shooting in a set, so the toilets in the ‘house’ aren’t actually real) cost money. The vehicles to transport all this stuff around costs money. The food and drink that keep the crew going cost money. The people who run the payroll that pays for all these people and keeps track of expenses, gets permissions to shoot on locations, hires out studios, makes sure their vehicles are gassed up, photocopies the scripts, makes sure people turn up on time at the right place at the start of each day and generally runs the office paperwork of the film cost money.

And this is just the camera and lighting departments. What about the actors who need to be paid for their time and talent? The makeup and hair artists who make sure the performers look the right combination of “realistic” and “interesting/sexy”? The wardrobe department who not only ensures that the actors wear the right clothes for the right scenes (and those clothes are often hand-picked and/or hand-designed/created/distressed to fit the “world” of the film) but also ensure those clothes are washed and cleaned every night and ready for the next day’s worth of filming?

What about the art department – the people who, literally, build the world the actors walk around in and camera photographs – who designed the room in that scene, filled it with hand-picked props that reflects the character of the person who owns the house and would look good on-camera when the actors picked them up and used them in the story, who ensured that tiny details like the color of the drapes didn’t clash with the color of the actors costumes, who spent weeks preparing that living room to look like any other living room in the USA except this one was the most interesting, dynamic, dramatic and perfect living room for THIS scene in THIS movie and yet, the whole time, making it look like it’s completely natural, realistic and almost run-of-the-mill?

They all cost money.

Then there’s the people who record the sound during the shoot. The people who ensure that the film or digital media makes it back to the editing suite at the end of the day. The people who edit the film. Who color-grade the film. Who write the music for the film. Who record the music, who mix the soundtrack, who do the visual effects. The people who are in charge of ensuring that all the machinery used to edit, grade, score and mix a film doesn’t break down. And then there’s the people in charge of printing the film so it can get copied and sent to cinemas. And between every single one of those people, the tiny, small, dedicated, insane team of people, who run around making coffee for everyone else. THEY ALL COST MONEY.

Movies cost money because movies make real life seem larger than life. And in order to make real life seem larger than life, you have to artificially rebuild real life from scratch and make it bigger, badder, bolder and more over-the-top than the real world actually is. If you don’t make your movie larger than life then you end up with a movie that either looks like a documentary (which could be okay in some circumstances) or looks like “Timmy’s First Home Movie” (which is never okay unless you happen to be Timmy).

So how on earth to do you make a “low-budget” movie?

Let’s look at our formula again: if time equals money, energy equals money and a movie is the result of time and energy and, therefore, a movie is the result of money…then you have to reduce the amount of money in that equation by one, two or a combination of:

* REDUCING THE AMOUNT OF TIME

* REDUCING THE AMOUNT OF ENERGY

* GETTING TIME & ENERGY DONATED FOR A DISCOUNT

In other words, you can make your movie really quickly, you can make your movie by reducing the number of people working on it (which could make the film take longer to shoot) or you get people to donate their time and energy for cheap or free. And THAT is the “low-budget” movie: something shot quickly, something shot by very few people or something shot on a voluntary basis. And if you’re lucky or smart, the film won’t look like “Timmy & The Quest To Scale The Mulch Pile In The Back Yard”.

A scene from "BIRDEMIC". A magnum opus truly worthy of Timmy.

In effect, there is no such thing as a “low budget film” technically because films expend the same amount of cost – whether it’s financial, environmental, logistical or purely just personal – to get made. And sometimes, in the case of bad low-budget films, the cost comes out in the quality if you’re not willing to put enough time, energy or people up front. Low-budget films still need gas for cars, food for people, actors to play characters, humans to operate the gear and make creative decisions, locations to set the story in and enough technical know-how to ensure that you finish the thing you set out to make. Nothing really changes in that equation, just the circumstances on how those things are brought together. Good low-budget filmmakers know how to bring those elements together with minimum cost to themselves and the movie, but maximum value for audience and the people who helped bring the film to life.

The success of various low-budget films come from a range of, mostly, creative based decisions surrounding the story that anchors the film and the approach to getting the film made. In almost all circumstances (bar the odd rare exception), the most important tactic for every low-budget filmmaker is “the plan”: which is deciding, long before you start photography, how you’re going to shoot, edit and present the film. Having a plan is the low-budget filmmaker’s best friend and those directors who can see entire movies unrolling before their eyes without having recorded a single shot always have an advantage in this area (though they are not exclusively great low-budget filmmakers). Planning out the shoot (which essentially is the whole of the pre-production process) gives you a perfect overall picture of what needs to be achieved cinematically and then those elements can be broken down into individual pieces (whether its locations, actors, props, special effects or just individual shots) so decisions can be made as to whether those aspects will be shot fast, shot with as few people involved as possible, shot without spending money or possibly dumped if it proves impossible to achieve with the standard budget. A solid and pragmatic plan of what to shoot and how to pay for it, coupled with a sensible script that can be pulled off with a combination of carefully measured time, energy and charity, can (and has) theoretically come together to produce a fantastic film.

There are a slew of such excellent and beautifully executed low-budget films (here defined by under $1 million in adjusted USD) to look at such as Robert Rodriguez’s famous action-packed Mexploitation El Mariachi (and its accompanying “making-of” book Rebel Without A Crew and famous DVD commentary and empowering extras like the Ten Minute Film School), Kevin Smith’s counter-culture classic Clerks (the making of which is documented in The Snowball Effect video), the time-travel mind-screw Primer, the trope-creating found-footage film The Blair Witch Project and its spiritual successor Paranormal Activity, Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (the making-of-which is documented in Bruce Campbell’s hilarious autobiography If Chins Could Kill), Romero’s flesh-eating-zombie-genre-creating Night Of The Living Dead, David Lynch’s Eraserhead, the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre, John Carpenter’s Halloween, the original (and still bizarre) Aussie classic Mad Max, the indie musical Once, the inspired-by-true-events shark movie Open Water, Darren Aronofsky’s cult first feature Pi, the infamous and insane Peter Jackson debut feature Bad Taste (the making-of documented in the short film Good Taste Made Bad Taste) and many, many more.

And, of course, because movies cost money, people are reluctant to give money to people who haven’t made movies before. So young filmmakers start out their careers by, naturally, making low-budget films. So in theory the trick then for these young filmmakers (including the ultimate winner of Make My Movie) is to ensure they don’t make a film that sucks; either functionally (which prevents it from getting sold) or aesthetically (which prevents an audience from enjoying it). And that certainly is some trick!

There are no real answers for young filmmakers like myself, we just have to know that our particular equation for making a film on a particular budget is going to work and going to make a return. That’s where things like talent, luck, preparation and that amorphous quantity of “knowing what you’re doing” comes into play. And that is the roulette game of film production – that people who put together low-budget films must have faith in the creative minds who are trying to bring it about and the industrious laborers who are working for next-to-nothing because they want this film to be something special, something they are proud to have their names on. Low budget films have started some very successful careers in the movie industry and it is for that reason that people are willing to shoot fast, shoot cheap or just work themselves to the bone for a noble, creative cause.

So on a more personal (and self-promotional) note…what about my movie?

Well, picture this if you will: you’re a tourist or perhaps someone on a holiday, hiking 3 days deep into some of our country’s most rugged and beautiful wilderness. You haven’t seen a single living soul as you’ve traversed some difficult terrain through some of the lesser known tramping trails, seeing some amazing sights and taking in nature at its finest. But what you’re not aware of…is that you’re being hunted. You’re being watched. You’re being tracked and hemmed in for the kill. Someone has been altering the trail markers, hiding the turns onto easier paths, guiding you deliberately deeper and deeper into the bush…where the trap is waiting!

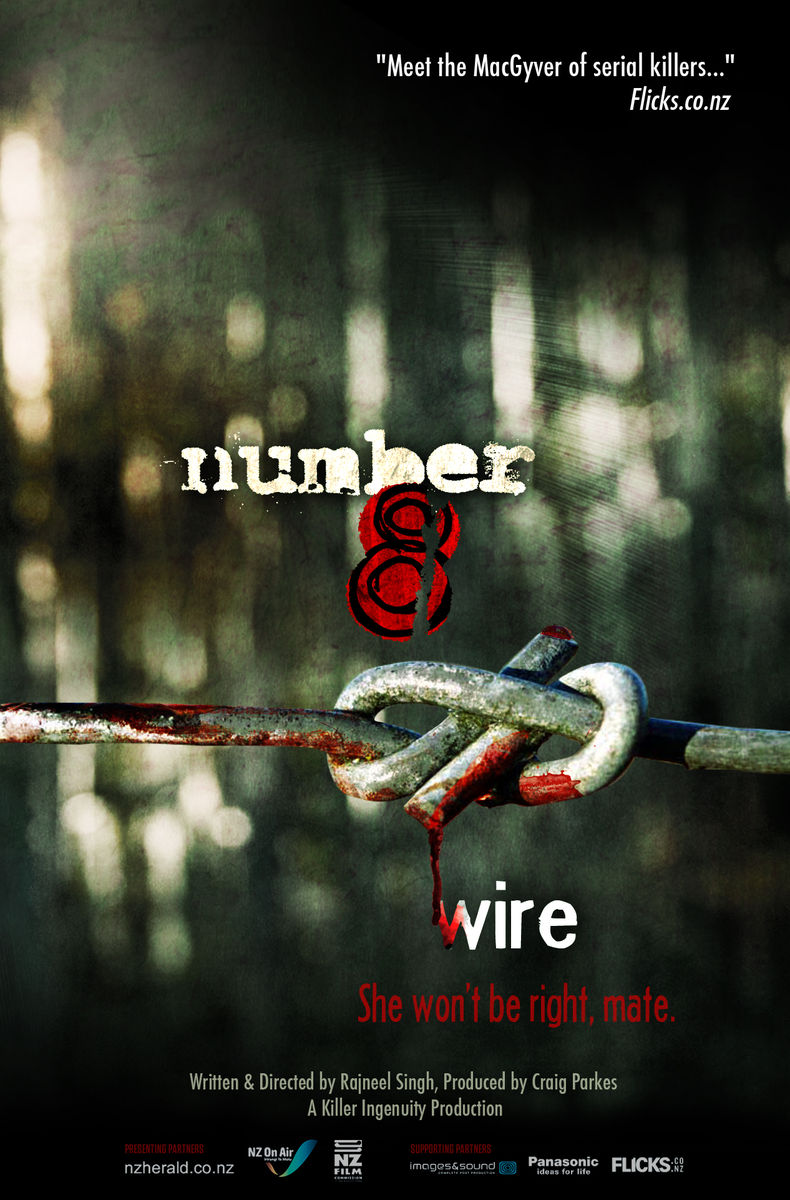

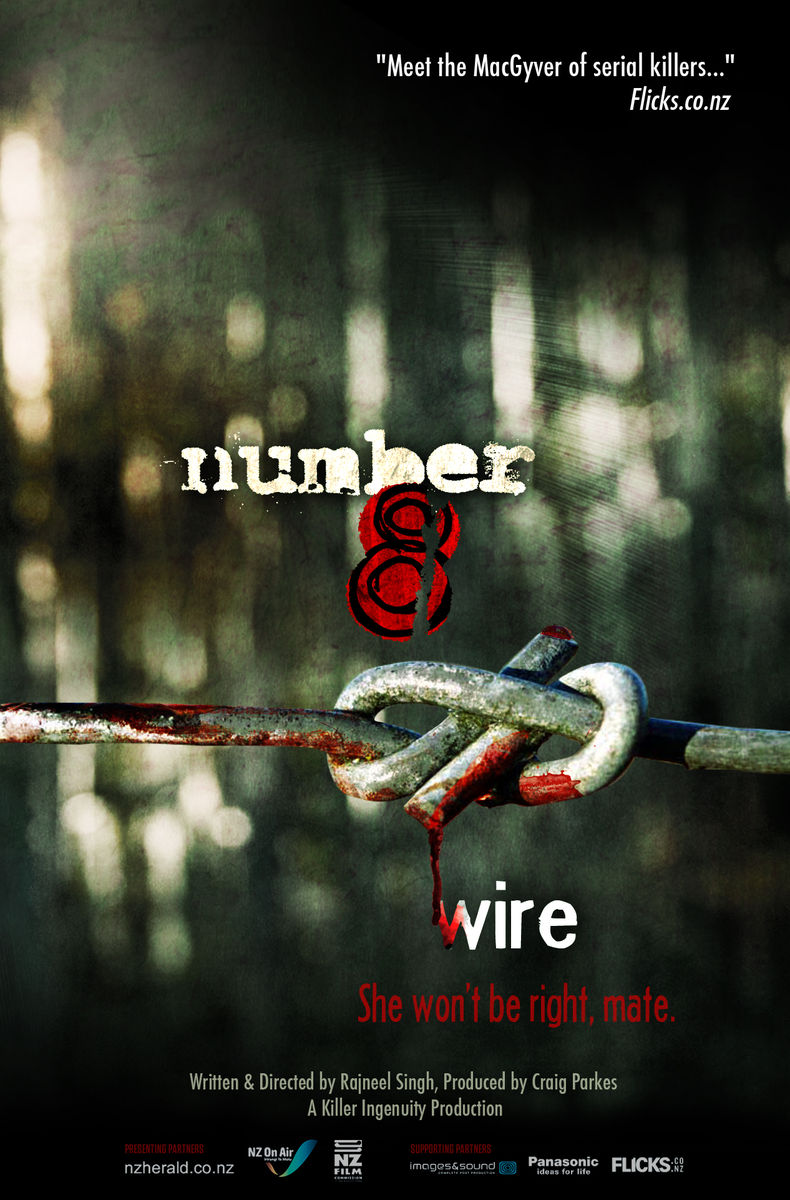

Meet the MacGyver of serial killers and the antagonist of our Make My Movie project Number 8 Wire. Our killer is a master survivalist, trapper and ingenious designer of complex, Rube-Goldbergian death traps that they’ve laid out all throughout the forest. Constructed entirely from parts scavenged from the edge of civilization, household items and hand-crafted bush and tree materials, these traps form the basis of a deadly cat-and-mouse game our killer will play with you and anyone else that crosses their path!

Thrown into this game are our protagonists: a New Zealand LAND Search & Rescue team that have been called in to rescue a lost hiker who has sent a GPS distress signal. Our team suits up and heads out into the unknown, not realizing that they’re being setup by our mysterious antagonist who has a fiendish array of toys waiting for them.

Making movies of any sort, low-budget or otherwise, is difficult and our project presents its own set of unique challenges to overcome. Apart from the design and execution of the traps (which need to be memorable, clever and interesting), the notion of shooting a film that’s almost entirely outdoors presents issues in terms of location shooting, working around weather, available sunlight and audio issues. And while we have deliberately created a film that demands less on art department and cast by limiting it to a small number of actors in the bush, there are additional things to worry about like making the footage look cinematic and interesting (as our bush can often end up looking very flat and uninteresting) and working with location and budget issues to execute the film’s death and stunt sequences as well as tell a gripping, action-orientated, thriller about extreme survival.

One of our ideas to offset the cost (and by adding more “time” as a resource) is to hire a group of second-unit ‘guest directors’ who will take one an individual trap and shoot a particular character’s demise. Another idea, tied to splitting the team into two units, is to base the trap scenes around a central location where we can setup a mobile workshop and ensure that while we maybe in the deep forest capturing the drama and the best photography, our “kill crews” are knocking off deaths and springing traps one after another within walking distance from each other and a fully powered office. Naturally demands on wardrobe will be lesser to some degree since nobody really changes their clothes and there is plenty of room for sponsorship from many of New Zealand’s outdoors and sports-gear companies. And having had a long history in the field of post-production, we can offset costs by doing the bulk of the editing and assembly of the film ourself before more experienced individuals like colorists, sound-designers, composers and mixers step into the process and begin chewing through our expenditure.

In terms of marketing and release, one of the advantages of the MAKE MY MOVIE competition process is raising the awareness of the projects within the local public eye and mindset and this will be instrumental in building a fanbase and ensuring audiences will turn up and check out our film wherever it may be screened. All these aspects will come into play should our film be the winning entry in this competition and, if that happens, you’ll be lucky enough to see if I can really put my money where my mouth is and make a low-budget film that works!

Lastly, before I go, here’s a 4-minute pitch reel for our project that describes some of our ideas, plans and solutions for the upcoming film shoot. Enjoy and please don’t forget to vote for our project and share it with your friends: http://www.number8wiremovie.com!

Thanks for reading!