The Naked Gun makes comedy feel gloriously reckless again

Hilarious and proudly out-of-time, The Naked Gun reboot revives the anything-goes chaos of classic gag-heavy comedies.

Make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh. The new The Naked Gun feels fresh ironically because it seems to belong to another era in comedy—when everything was about the joke, and nothing else mattered. That time never really existed: even riotous balls-to-the-wall classics like Airplane! (a clear influence) and the original Naked Gun trilogy (ditto, obviously) made all sorts of calculations that audiences were never privy to. But they felt like nothing was off limits—and that “the line” was something considered afterwards, if or when it’d been crossed.

The dangerous art of outrageous comedy involves being taken into loaded, uncomfortable spaces, where you begin to feel distrust towards the joke-maker and wary of your complicity in something potentially wrong—only for them to get you back onside (hopefully) and keep the ball rolling. It’s not an exact art, and even great joke-makers fall short.

Comedy legend David Zucker, one of the brains behind Airplane!, has defended that film’s now-controversial “I speak jive” joke, on the grounds that it pokes fun at the language of both white and black people (“the bit was evenhanded because we made fun of both points of view,” he wrote). But I doubt even Zucker, in his heart of hearts, would want to rehash it. There’s too much real-world baggage, too many sensitivities, too little pay-off. In these moments the film loses its endearing blitheness and becomes something else.

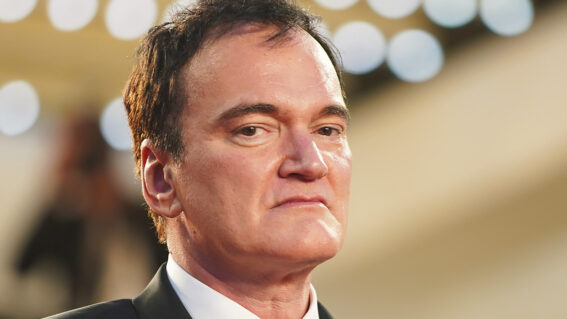

I wonder if, in the future, we’ll come to view any of the gags from the new The Naked Gun in that light. Director Akiva Schaffer’s very funny film is, like its even funnier antecedents, insulated by two core elements: absurdity and dad jokes. It begins with a bank heist in which a thief steals a plot device—as in: an object labelled “plot device.” Before we know it, Liam Neeson’s Lt. Frank Drebin Jr. (the son of Leslie Nielsen’s Mr Magoo-like character from the originals) has infiltrated the heist and is kicking ass. At one point he snatches a robber’s gun and literally eats it, as if it were made of cookie dough.

In this scene the screenwriters (Schaffer, Dan Gregor, Doug Mand) re-establish the rules of the Naked Gun universe. Which is to say, there are none; no fundamental principles govern this cosmos. Time, gravity, chemical properties, the third wall, the fourth wall, whatever—everything can be added, subtracted, bent, obliterated in service of that core objective: make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh. The film dives into a cartoonish space from which its liberated from reality but needs to keep being very funny very quickly, to compensate for the lack of other foundational elements i.e. engaging character arcs and narratives.

There is a plotline involving an evil genius: Danny Huston’s billionaire Richard Cane, who wants to take over the world via new technology that regresses people to the state of dumb beasts. But this plot thread is so inane it’s barely worth mentioning, and, anyway, focus is pushed onto the protagonist from every direction; he’s almost villainous himself. When Drebin Jr. gets dressed down by a superior for behaving recklessly, he fires back, with complete sincerity: “since when do cops have to follow the law?”

And the dad jokes? Oh, the dad jokes. When Pamela Anderson’s faux femme fatale Beth Davenport arrives in Drebin Jr.’s office, he offers her a seat. She declines, explaining that she has plenty of seats at home—but later changes her mind, lugging a chair out of the room with her. There must’ve been a zillion variations of this gag over the years, maybe over the centuries, maybe since the invention of chairs. Dad jokes like this are more filler than killer but they help pace-wise, and partially it’s a numbers game: the writers absolutely pelt us with gags, believing, knowing, many will stick.

Another vessel for The Naked Gun‘s outlandishness has literary origins: its spoof gumshoe narration, parodying detective novels and of course noir films. At one point Drebin Jr. describes Davenport as having “a bottom that would make any toilet beg for the brown.”

At the risk of attempting to analyse the bowel movements, er, science of toilet gags, this line is a good example of the film’s ability to catch us off guard. You’re not sure how to handle it, and you sweat on it for a bit. Neeson isn’t a naturally gifted comic (like Nielsen) so he delivers this dialogue—all his dialogue—in the only way that makes sense: jet-black deadpan. The man has one card to play and boy does he play it, with Terminator-like focus on that core objective: make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh, make ‘em laugh.