Washington Black navigates steampunk fantasy and the horrors of slavery

Has Washington Black correctly acknowledged the pain, while seeking the proper amount of joy? In any case, it’s thoughtful and earnest to its core.

How do you honour suffering without exploiting it? How do you celebrate resilience without smoothing out the pain? These questions haunt every work set within history’s darkest passages. Yet, Esi Edugyan’s 2018 novel Washington Black, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, achieved an unexpected balance in this respect: it’s a 19th-century-set, Jules Verne-esque tale of explorers, scientists, and flying machines, yet its young hero was born in the Bahamas into slavery. Nothing is compromised—neither the brutality of this world, nor the wonder that can be sought high up in the air, or far out on the ice floes.

Its Disney+ adaptation, created by Selwyn Seyfu Hinds, has snipped much of the violence, turning its attentions instead to the studio’s own history of sweeping, romantic adventure pictures, specifically its adaptation of Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Its score is explicitly sentimental. The book’s too plausible in its steampunk machines to count as magical realism, but it certainly relies on that slightly dreamy, immaterial quality. And whatever impressionistic ambiguity you can keep on the page, and in the imaginations of readers, is ultimately lost here. As a result, it has the quality of a children’s story, while retaining somewhat graphic depictions of injuries and broaching the subjects of suicide and torture.

Related reading:

* The Bear reaches a profound understanding

* Italy now has its own The Crown

* The best shows of 2025 so far

It’s a little unexpected, but I’d hardly call Washington Black a failure, since its fantasies are never allowed to detract from the sincerity of Edugyan’s contemplation of Black identity and family under perpetual assault from the imperialistic system.

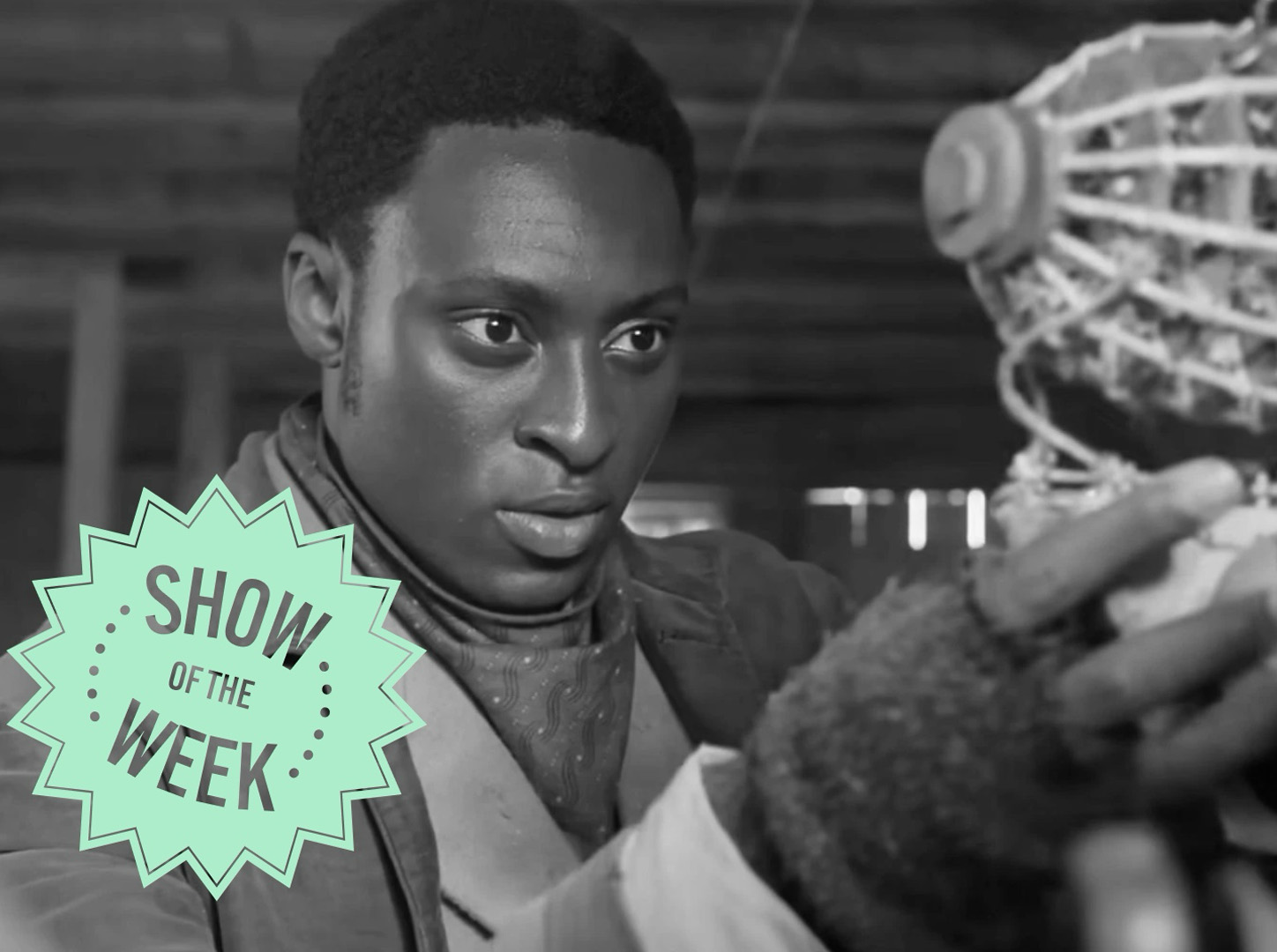

Its eight episodes (critics were given access to four) carves the book’s bildungsroman structure in two, flashing back and forward between George Washington “Wash” Black as an 11 year old (Eddie Karanja) on a sugar plantation, raised by his adoptive mother Big Kit (Shaunette Renée Wilson), and as an adult (Ernest Kingsley Jr) living at the last stop on the Underground Railroad in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He dwells there under the protection of community leader Medwin Harris (Sterling K. Brown), another parental figure for him.

This choice of structure allows Washington Black to dangle a few cliffhangers in our faces, while jumping around in time (even the flashbacks aren’t in chronological order) in order to withhold certain tantalising pieces of information. It takes several episodes, for example, to get a clear picture of how Wash was able to escape the plantation and slave owner Erasmus Wilde (Julian Rhind-Tutt).

We know it’s with the help of his brother, scientist and abolitionist Christopher ‘Titch’ Wilde (Tom Ellis), who also encourages him in his curiosity and education—yet, that doesn’t explain why, as an adult, he has men on his tail wielding an accusation of murder. It’s a little bit of television trickery, but the series is neither cheap nor careless when it comes to its story, and there’s a delicate handling of Edugyan’s core ideas here.

The look and tone might feel simple, but the morality at hand is not, and the series presents us with complicated figures on all sides: of what it takes Medwin to protect the fragile community he’s built around him; how Titch can be an honest abolitionist yet still greatly harm his new ward; or how Wash’s love interest, Tanna Goff (Iola Evans), must navigate her identity as a biracial, white passing woman—whose father (Rupert Graves) has severed all connections to her mother’s home in the Solomon Islands, for what he believes is her protection.

Has Washington Black correctly acknowledged the pain, while seeking the proper amount of joy? It’s easy to ask, near-impossible to definitively answer. But, in any case, what has been achieved here is thoughtful and earnest to its core.