“We’ve become very, very paranoid”: Ari Aster explains Eddington

“It’s a film about the environment we’re living in right now, which is one in which we’re all siloed off from each other.”

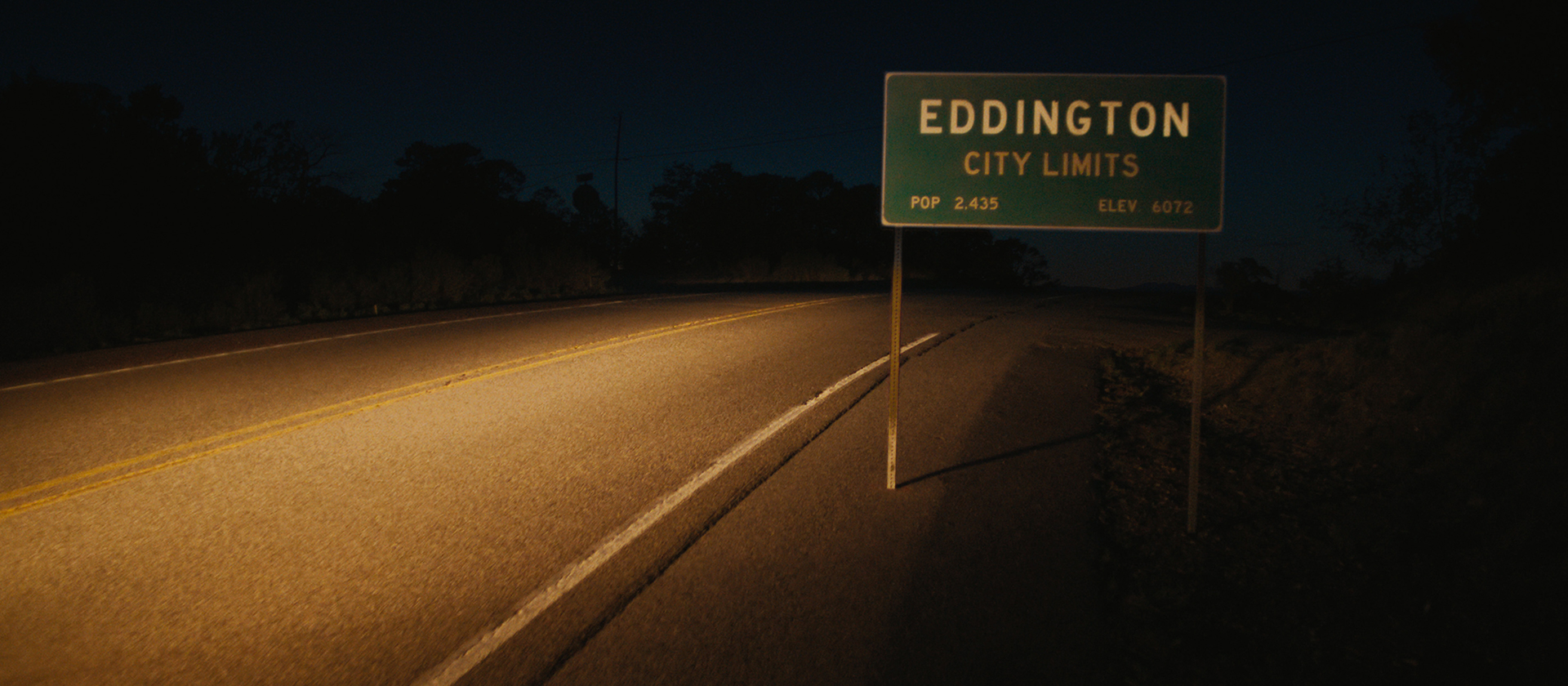

In a small, isolated New Mexico town, an emasculated sheriff channels the tension of his home life into a feud with the charming but corrupt mayor. Plans to install an environmentally costly data centre show how ambitious the town’s leaders are, while the early policies of the COVID-19 pandemic trigger ordinary, alienated townsfolk to erupt with frustration. Where does everybody turn? To digital worlds where everything feels more certain, personal, and paranoid. This is Eddington, the latest work by Ari Aster, where everybody’s brain is now wired differently.

Aster’s first film grounded in a real, specific moment features just as much dread and uncertainty as his films about cults, demons, and psychosexual odysseys. But Eddington also acts as a sort of homecoming for the director, who until now has stayed away from depicting life in his home state.

“I basically spent all of my adolescence in New Mexico. My family still lives there,” says the director, speaking to Flicks on Zoom. “It’s probably the region that I know best. When I was a lot younger, I had a real problem with it. I didn’t like it. I’ve come to really like it, and part of that came when I was shooting the film.”

Eddington stars Joaquin Phoenix as Sheriff Joe Cross, who lives with his timid, unwell wife Louise (Emma Stone) and her conspiracy-obsessed, widowed mother Dawn (Deirdre O’Connell). It’s a household where everyone’s trapped by their own distinct pain—and after Joe defends a local anti-mask “free speech” advocate in a supermarket, he decides to take back control by running against Mayor Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal).

“It’s a film about the environment we’re living in right now, which is one in which we’re all siloed off from each other,” says Aster. “In that fortressing-off, we’ve become totally unreachable, and because we’re so isolated, we’ve become very, very paranoid. We all know that something is really wrong. Things are changing very quickly, but we don’t agree on what that thing is.”

Eddington satirises safe and sensitive political topics alike, but what elevates Aster’s film from an easy lampoon on 2020’s loudest voices is the sense that everyone listens so selectively that they’re only capable of hearing what affirms their worldview.

“It begins with the writing, where you have two people on their own tracks, speaking over each other, which felt important because that’s a huge part of being alive in the world today with other people,” said Aster. “But for me, it was important to make sure that all the people in the movie make sense. To know what their histories are, to know what their fears are, what their yearnings are. I just knew that the minute that I stooped to condescension in any direction, the film would lose interest or purpose.”

As Joe pursues public office, the grudge between Ted and him explodes with low blow attacks and public humiliations. Phoenix’s ability to channel indignant emasculation has never been better utilised, and Pascal’s confident charisma mixed with beleaguered sternness becomes a perfect foil.

“He’s one of the more cynical characters in the film,” says Aster about Ted. “He’s a politician in the truest sense, somebody who espouses one thing but then does another. […] But he’s also obfuscating a lot. He’s fleeing from a lot in his own life.”

Phoenix previously starred in Aster’s Beau is Afraid, but was excited by Pascal’s arrival to the AsterVerse. “I was really gratified to see how much chemistry [Pedro] had with Joaquin,” said Aster. “They really liked each other, and they really liked working together. You never know when that’s going to happen. I found that those days where they were both together were kind of uniquely electric.”

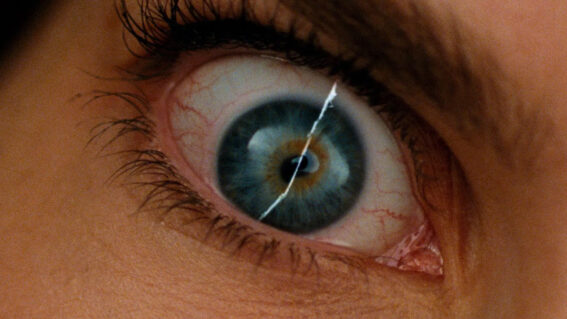

As much as Eddington understands how the internet has been exploited by politicians and corporations, Aster knew how feebly a screed against phone overuse would come across on-screen. “I wanted to really underscore the presence of these phones and just how insidious they are, because there are plenty of films that feature technology and people on their phones, but there’s something benign about it. Where somebody texts and [there’s] like a ding or maybe a bloop as the text bubble shows up, and it’s kind of cute.”

The way they valorise technology’s powers of alienation is what struck Aster most. “We’re racing towards this new age of this new technology. If you listen to the people [ushering it in], they’re very worshipful of it. They sound more like disciples than they do technicians or inventors. I wanted to just keep underscoring the strangeness of it, and keep those phones foregrounded in a way that is almost queasy.”

“Almost queasy” is an understated way of describing Eddington‘s final act, which takes the hysterical accusations of conspiracy and persecution that have filled the previous two hours and introduces into a violent presence into the town that best goes unspoiled.

Aster saw it as a necessary invasion of the characters’ mood into the story itself. “It felt important that the movie become paranoid too. The first half is about a bunch of people who have very clear ideas about the designs around them. And it just felt right that the movie itself should become gripped by that same fear and conspiracy thinking.”