Cowboy Bebop and the challenges of adapting animation for a live-action series

Before judging the Netflix Bebop, just what is and isn’t possible in translating animation to the live-action medium?

Netflix’s New Zealand-shot live-action Cowboy Bebop has been a long time coming – and as with any adaptation of beloved source material, fans of the original have had mixed responses. Here Dan Taipua looks at what is and isn’t possible in translating animation to the live-action medium.

(This review contains light spoilers for the 1998 anime version of Cowboy Bebop, without spoiling the new version)

After delays in production with the COVID pandemic and the unfortunate injury of lead actor John Cho, the live-action adaptation of Cowboy Bebop finally arrives on Netflix this week. First aired in 1998, the Cowboy Bebop anime was set in a hyper-globalised future that spread into the stars, fusing together the great works of 20th century pop culture into an animated melting pot: Jazz, Sci-Fi, Film Noir, Kung Fu and the French New Wave all coalesce in a surprisingly mature tale of space-hopping bounty hunters.

With such a long period of anticipation between the announcement of the live-action series and its eventual release, fan expectations for the new series are running high, with many wondering if the in-person version of the classic anime can live up to its treasured history. But judging the success of an adapted work isn’t straightforward, and it’s worth examining what is and isn’t possible in the live-action medium.

Form and Format

The original Cowboy Bebop isn’t just an anime, but a television series, developed to fit the criteria of broadcast: 26 episodes, 24 minutes in length, with interstitial breaks for advertising, aired on a weekly basis. Everything about the show’s storytelling flows from that television format: the broad and frequently interrupted arc of the revenge storyline, the syncopated introduction and fleshing-out of characters, the slice-of-life insights into environment; each is revealed and developed in a meter set by the format of weekly episodes.

Stylised as ‘sessions’ to evoke a musical theme, each original episode works like tracks on a mixtape or the movements in an improvisation—the overall substance and intention of the broader work is expressed in smaller and often divergent pieces. The ‘Bebop’ in the original show’s title hints at its structure through the features of the jazz musical form: Theme, Suspense, Variation; each playing within the storytelling structure of the series to create a cohesive and expressive whole.

In contrast to the tight restrictions of ’90s television, modern streaming has far fewer constraints on time: 10 episodes, 45~60 minutes in length, no advertising breaks, with all episodes available immediately. This change in format fundamentally changes the way storytelling is structured across the series, moving away from thematised snippets of the episodic form and into longer and more tightly woven narrative arcs that characterise one-hour drama.

The availability of all episodes at once means the show has to be ‘bingeable’ and proceed at a pace that allows uninterrupted viewing, with two major effects. Firstly it removes the repetitive pattern of the anime, which across 26 weekly broadcasts needed to reintroduce and reify character and setting every few episodes. Secondly, it removes the need or desire for the so-called ‘pocket’ episodes which have no effect on the broader arc of the series and are just a spot of fun, like the original episode where sentient slime attacks the Bebop crew without any long term effect.

Returning to the jazz metaphor, the ‘Bebop’ of the anime is translated into ‘Cool Jazz’ for the live-action drama, from hot and loose to controlled and smooth. Both are worthy and popular styles of Jazz, but many fans will favour one over the other.

Pencil vs. People

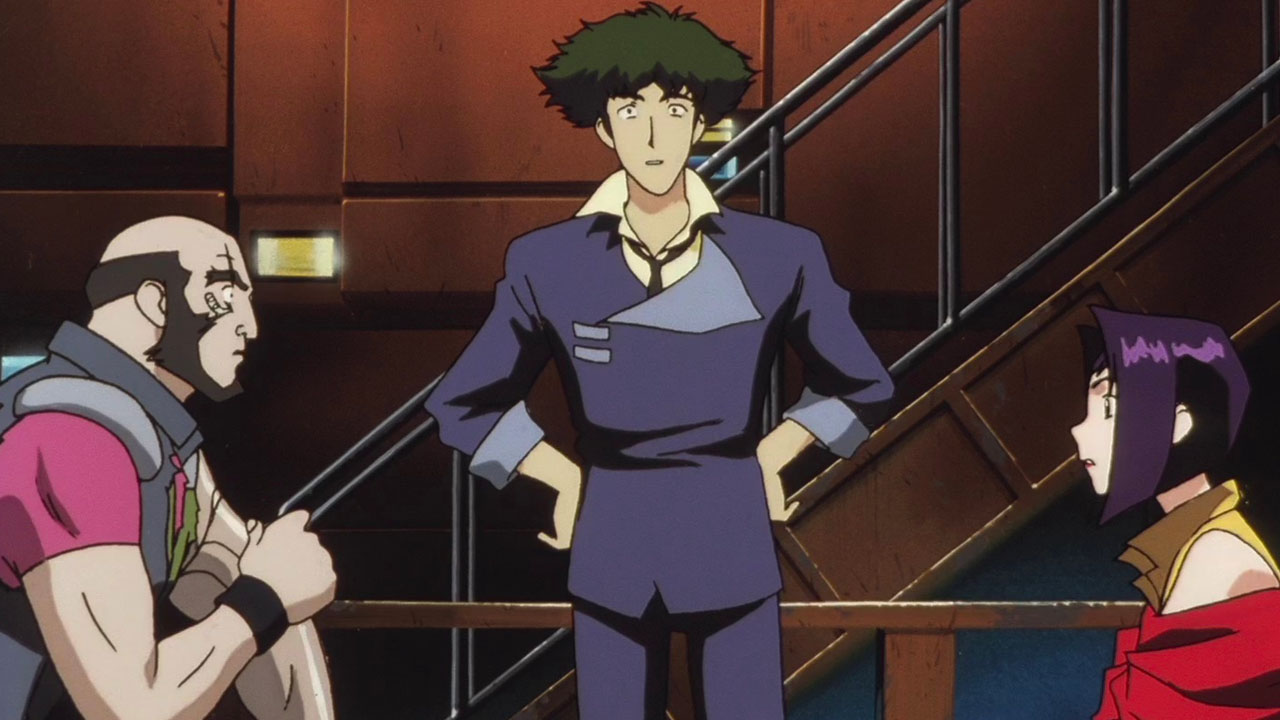

The most obvious challenge in adapting an animated work is finding an appropriate visual style. It stands to reason that hand-drawn pictures will allow anime to show things that simply can’t be reproduced with actors in a physical space: you can’t have John Cho eat a lit cigarette like Spike Spiegel does in the original. Aside from the obvious elements like character design and physical proportions, colour saturation and hue, and cartoonish visual gags; anime as a medium presents other unique qualities related to visual information.

The original Cowboy Bebop relies heavily on the use of montage, leaning on animation’s much more simplified physical space to communicate a very dense amount of information within a short time—cuts are jumpy and often in extreme close-up, giving the work a very kinetic feel. This montage effect also allows for extended use of voiceover and the presentation of hyper-detailed graphical information, where screens or data or extreme close-ups of objects can fill the screen without disorienting the viewer. As well as being a distinct visual artform, the animated medium also has a language and grammar of its own which can’t be detached or reformed in adaptation.

The live-action Bebop has to perform a lot of compensations and create solutions for the impossible grammar of anime, and for the most part succeeds quite well. The production design for the show, its sets and props and scenery, build an interesting and detailed physical world assisted by CGI in ways that are less obvious than one might expect. A lot of heavy lifting is performed by the use of classic cars and mid-20th century décor but this is very much in-line with the design philosophy of Bebop’s hodge-podge universe where past melds into the future.

The more difficult compensation for montage and character is carried by the cast’s performances, and the re-focus of material through the lens of drama—and it’s little surprise that the presence of real humans should make the material realer and more human. The hyper-energetic style of Cowboy Bebop is slowed down and stretched out by a script that prioritises interaction and development of its characters, giving a fuller and more explicit picture of their internal lives.

For first-time viewers this will be almost invisible as it matches the tone and pace of other sci-fi/action works of this decade, with the lead writer coming from Thor: Ragnarok, and the lead director coming from Netflix’s Daredevil and The Punisher.

Revisit and Replace

Cowboy Bebop was made a long time ago with a very particular audience in mind, aimed at an audience of young-to-adult men watching television in Japan in 1998. Even then, a lot of the original content was considered ‘too adult’ and had to be dropped from broadcast. Now on Netflix, the live-action adaptation has free-reign for content but also has to conform to the expectations of a broader global audience, almost a whole generation apart from the original show. This cultural and generational divide shows itself as early as the first episode, with adjustments to characters (pointedly, mostly women) that bring them inline with the 2020s while allowing for the kind of long character arcs mentioned earlier.

The stylised action of the original has also been updated, veering away from 1970s Bruce Lee and 1980s John Woo towards 2010s John Wick. The cultural and generational changes to Bebop drain away much of the original’s verve, but make the show much more legible to a new audience. It keeps the killer-for-hire clown Pierrot Le Fou, but loses sight of the reason he might be named that. It loses the character archetypes of Lupin III, but gains the character archetypes of Sin City.

Back in 1998, the original Cowboy Bebop would display the following manifesto after ad breaks: “The works, which becomes a new genre itself, will be called Cowboy Bebop”. The 2021 live-action show is a work inside of that genre, mixing together similar styles with a new sound for a new audience that some will warm to immediately and others will shy away from. Whichever camp the viewer falls into, Netflix also hosts the entire original anime in a beautiful HD transfer, making sure the classics are still in rotation.