The Burnt Orange Heresy is more fizzer than a seductive neo-noir

Aaron Yap finds that outside the cast’s charisma, there’s little to recommend.

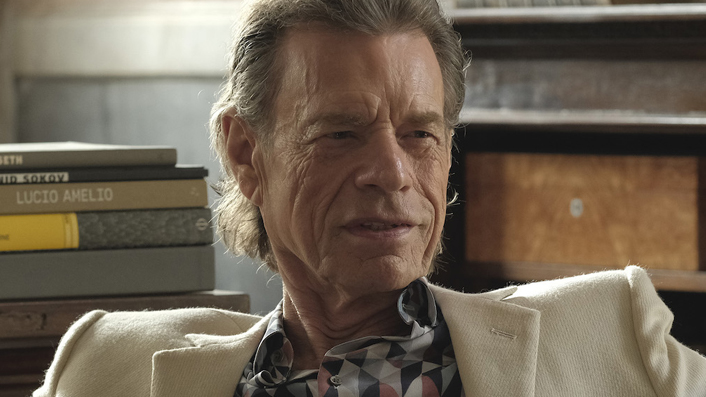

Claes Bang (The Square), Elizabeth Debicki (Widows), Mick Jagger and Donald Sutherland star in neo-noir thriller The Burnt Orange Heresy, set in the art world of present day Italy. Unfortunately, Aaron Yap found that outside the cast’s charisma, there’s little to recommend.

Given his stature as one of the great crime writers of the 20th century, it’s curious that only a handful of Charles Willeford’s works have made it to the big screen. The few that have, such as Cockfighter and Miami Blues, are distinctively offbeat pulp gems that have deservedly garnered a cult following over the years. This adaptation of his 1971 novel The Burnt Orange Heresy however, is a bit of a middle-of-the-road fizzer, neither compelling as a cynical critique of the modern art world nor the twisty, seductive neo-noir it’s striving to be.

See also:

* The best thrillers of last decade

* Everything now playing in cinemas

The film opens with a masterful scene-setter, cackling with an energy that never returns. Lecturing to impressionable tourists in Milan, Italy, art critic James Figueras (Claes Bang) unpacks the historical context behind a seemingly shoddy abstract painting, slowly peeling away layers of meaning and forcing us to reorient our perspectives.

The scene smartly foreshadows the slippery intersection of art, commerce and truth that crystallises as Figueras finds himself orbiting around a trio of characters with cloudy motivations: free-spirited American teacher Berenice Hollis (Elizabeth Debicki), affluent art collector Joseph Cassidy (Mick Jagger) and reclusive artist Jerome Debney (Donald Sutherland).

The appeal of watching these fabulous, perfectly able performers casting aspersions on each other in the idyllic surroundings of Lake Como is not lost on me. Jagger having a ball, saying things like “Art is a harsh mistress”. Bang turning on his best peak-Brosnan urbane charm. Debicki enlivening every scene she is in. But the stars’ charisma can only do so much heavy lifting to sustain narrative interest. Giuseppe Capotondi’s direction leans toward sleepy and formally staid, lacking the pleasurable side of low-key and leisurely that generally works for this kind of material.

The Burnt Orange Heresy promises the wicked flytrap glee of a good David Mamet con, but comes off like middling Claude Chabrol, coasting on a false air of sophistication before curdling into B-thriller silliness in its final stretch.