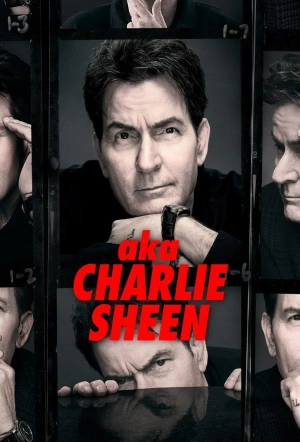

AKA Charlie Sheen delivers what we want: pure, uncut debauchery

From tiger blood to 18 hour nosebleeds, AKA Charlie Sheen serves unfiltered chaos and indulgence. It’s spectacle over substance, but very entertaining.

In the second episode of Netflix’s no-holds-barred tell-all about Charlie Sheen—debaucherous by definition, since it’s about Charlie Sheen—his ex-wife Denise Richards makes an early appearance. Addressing why she signed on, Richards quips that without her, the project would risk becoming “a fluffy, glossed-over, sugar-coated piece of shit.”

Having binged both episodes back-to-back, I can confirm: there’s nothing sugar-coated here. AKA Charlie Sheen is saturated with tales of indulgence and excess, delivering the audience exactly what we want. Sheen is more than happy to play his last ace card: the wizened former megastar candidly recounting how he partied too hard, went further than anyone else, and sailed over the edge—into that territory Hunter S. Thompson memorably described as a place only recognizable in hindsight (“the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over”).

The tone is confessional but chatty, with Sheen positioned around a table at a diner, ketchup and mustard observable in the same shot. It’s a clever setting: casual but not too relaxed—like a couch—and not too formal, like a studio. Director Andrew Renzi keeps the tone light and frisky, as if the production itself—like its subject back in the way—is a little tipsy, a little high and distractable, bouncing between conversational touch points like a pinball.

Importantly, for our enjoyment, Sheen knows how to distill his excessiveness into evocative turns of phrase, from blunt self-descriptions (“runaway train,” “high as shit”) to flashes of unexpected lyricism (“she showed up like a lighthouse in a storm”) to wild anecdotes that remind us why we’re watching (“one day I got an 18 hour nose bleed from doing too much cocaine”). Near the start, when asked whether anything is off limits, Sheen says no—and that certainly seems to be the case.

He is, as they say in documentary land, “good talent,” with a slightly hawkish look in his eyes I found difficult to place. I didn’t get the sense that this was someone weighed down by regret; even lines like “I feel awful about that, to this day” don’t seem to come from a place of deep reflection. Perhaps having a wary attitude towards the concept of regret is a smart move, even a survival instinct, for someone who’s messed up so many times, in so many ways.

One of Renzi’s visual techniques is to illustrate scenes from the past by, in addition to conventional dramatic recreations, splicing in moments from movies and TV shows—not necessarily Sheen’s. It works well, providing a loose, liberated quality: a kind of controlled chaos, through which the show can keep conjuring pop culture connections, for visual cadence rather than meaningfully drawing on other works. This creates an interesting if slightly reductive effect, contextualising the subject’s antics as part of a smorgasbord of media inputs and outputs: just another splotch of colour on the zeitgeist; more noise to tune in or out of.

The notable absence of the subject’s father, Martin Sheen, and brother Emilio Estevez, is addressed early on, Sheen saying words to the effect that he totally understands and accepts their decision not to be involved. It lends the show’s otherwise breezy, slap-happy rhythms a note of poignancy; the aforementioned pair must surely feel that they’ve been burned too many times.

Deep into the second episode, when Renzi arrives at the “winning” and “tiger blood” part of the subject’s life, there’s brief consideration of why audiences are so drawn to the Charlie Sheen shitshow, and have cut him so much slack—playing with the idea that he’s connected to a history of American outlaws, representing freedom from social constraints.

There’s a ring of truth to that, but don’t go into AKA Charlie Sheen expecting great insights. Its hollowness feels almost fitting, as if conceding that in Hollywood, spectacle is its own reward. After all the drugs and breakdowns, the heartaches and mishaps, what’s left of Charlie Sheen is just the show itself.