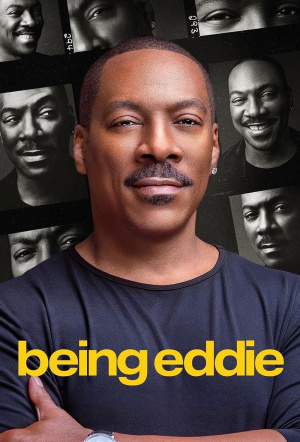

Being Eddie proves a satisfyingly watchable recap – if light on commentary

Netflix doco on comedy great Eddie Murphy fails to interrogate the charismatic entertainer – yet he’s still enough to justify a watch.

I’m not sure I need a feature-length documentary to tell me that Eddie Murphy is funny. Netflix’s latest, glossy artist’s portrait, Being Eddie, made off the back of the Renaissance man’s triple whammy of films with the streamer—Dolemite Is My Name (2019), You People (2023), and Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F (2024)—indulges in one of my least favourite habits of the genre: famous people describing famous film scenes and offering no more commentary beyond, “well isn’t he a genius?”

Yes, I know. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t agree. And nothing is being offered by it except the promotional suggestion that I watch Trading Places (1983) again once I’m done. Being Eddie, in that respect, is nothing but a creature of the algorithm, a little box to pop up once you’ve consumed one of Murphy’s films so you can be tempted to stay on the platform a little longer. Then you watch it, and the documentary ends, and another little box pops up with another Murphy film to consume in an endless cycle that doesn’t stop until you pass out or die.

There’s no interrogation in Being Eddie. Murphy fleetingly mentions his divorce and his ten children, but we never even hear the ex-wife’s name (Nicole Mitchell, by the way) or understand who these kids are beyond a wide shot of a jubilant hubbub around a kitchen table after the line, “family is everything”.

The recent Mr. Scorsese, over on Apple TV+, showed how even relative hagiography can embrace the inevitable complications of fame and parenthood, and that something can exist between ghoulish tabloid intrusion and hollow brand construction. There’s no mention here, for example, of when he initially denied he was the father of one of Melanie Brown’s children.

And so I spent the duration of Being Eddie, as I do with all documentaries of this breed, searching for the cracks, for the accidental reveals in what’s otherwise been thoroughly polished and controlled. Because Murphy, in his defence, doesn’t present himself as someone allergic to self-examination.

It’s only that director Angus Wall, who edited a string of David Fincher films, never seems to ask any follow-up questions (and that’s not in the Fincher spirit!). We don’t get to know what it really means for him to be a part of what he calls the “first generation of Black overachievers”, alongside Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey, and Michael Jordan—all of them, Murphy claims, inspired by the bravery and integrity of Muhammad Ali.

We don’t get to hear what it felt like the morning after the 1988 Oscars, after Murphy spoke out about the industry’s racism on stage, only for the media to essentially silence him the next day. It’s never questioned if he really, as he claims, cured his own OCD by simply shaming himself into ignoring his compulsions (this feels a little irresponsible on Wall’s part).

Yet, Being Eddie is still satisfyingly watchable, since between all the flattery from his fellow comedians—Chris Rock, Dave Chappelle, Tracee Ellis Ross, Jamie Foxx, and so on—we can follow the breadcrumb trail to a portrait of a man who succeeded through self-discipline.

Raised by a boxer stepfather, he didn’t indulge in drink, drugs, and rock’n’roll, didn’t stand in the centre of the room and scream for attention, but instead patiently moulded himself into the kind of man he wanted to be—Richard Pryor, Elvis, and the Beatles all rolled into one, in red leathers and a 1,000 kilowatt smile, a charmer as himself or as anyone he impersonated.

“At the root of it all, I love myself,” is Murphy’s conclusion. That’s one of the most beautifully refreshing things I’ve heard a celebrity say of themselves of late. It makes me wonder whether the fault, in fact, all lies with me. Here I am, dissatisfied because I can’t imagine an artist not at war with his shadow, when maybe there’s no interrogation to pursue because Murphy simply doesn’t believe there’s anything he needs to interrogate at this point in his life. That, or it’s all a PR exercise. Who can tell the difference anymore?