Cover-Up is a bracing reminder of why investigative journalism matters

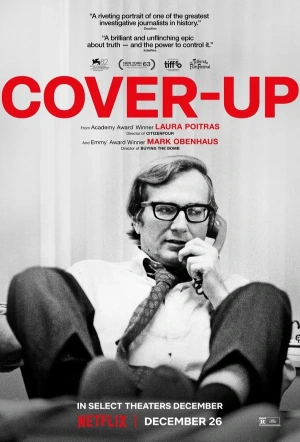

Now on Netflix, Cover-Up explores the career of legendary reporter Seymour M. Hersh and the battles behind publishing uncomfortable truths.

Journalists like Seymour M. Hersh—a legendary investigative reporter who’s been exposing high-level secrets and speaking truth to power for decades—have never been in great abundance. But there’s an unmistakable feeling, in the cold light of post-truth, Trump-era America, that they’re becoming an increasingly scarce commodity, sadly perhaps ultimately destined to go the way of the dodo.

To an extent, a film like Cover-Up, which unpacks Hersh’s life and highlights the crucial role investigative journalism plays in exposing government malfeasance, is always going to be relevant. But in the present moment this excellent documentary lands with alarming force, for many reasons—including the steady erosion of press freedoms by the hand of an American administration borrowing tactics from oppressive and authoritarian regimes.

Co-directors Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus don’t labor the point that their film is timely; that much is obvious. The same day I watched it, news broke about America’s clandestine attack on Venezuela, as well as revelations that the New York Times and the Washington Post had prior knowledge of the raid and chose not to report it. One of the major issues Hersh bumped up against throughout his long career, as we learn in Cover-Up, involved corporate pressures tied to the institutions he worked for—including the NYT, through which he broke many stories uncovering military and government abuses.

Having the story is one thing; being able to publish it is another—a theme central to Michael Mann’s great film The Insider, starring Russell Crowe as tobacco industry whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand and Al Pacino as a 60 Minutes producer. The case studies unpacked in Cover-Up are viewed through a journalistic prism in general and Hersh’s life in particular, from his exposure of the Vietnam War’s My Lai Massacre (for which he won a Pulitzer Prize) to, decades later, the Iraq War’s Abu Ghraib Prison Scandal, which he acknowledges would never have been a story without photographic evidence.

Small insights like that are peppered throughout this large and potentially unwieldy story, which comes together with surprising fluidity. It’s edited in an intuitive, explorative style that suggests the filmmakers are feeling their way through the material, crossing and segueing when it feels right, rather than following a predetermined arc or cookie-cutter template. This likely explains why it takes 40 minutes for Cover-Up to recount the details of Hersh’s early life, growing up in Chicago, helping out in his family’s dry cleaning store, then moving into journalism and working his way up from copyboy to crime reporter.

Hersh appears throughout, sitting down for at times bristly exchanges with the filmmakers, who are also respected journalists—Poitras for instance having won an Oscar for Citizenfour, her documentary about Edward Snowden. Journalists aren’t usually fanboys and fangirls of other journalists, which makes sense: their job is to see through the bullshit and engage with a critical eye. That sensibility surfaces in Hersh’s often combative responses; at one point, reflecting on how difficult it is to know whom to trust, he remarks: “I barely trust you guys.”

It also emerges in the directors’ choice to highlight some of Hersh’s biggest professional errors, which could easily have been ignored or minimalised, including being initially fooled by fake letters between John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe, and under-estimating the regime of Syrian autocrat Bashar al-Assad. “I really misjudged him…I didn’t think he was capable of doing what he did,” Hersh admits. When Poitras asks whether this is an example of getting too close to power, he shoots back: “Of course. What else is it?”

These moments create friction in the interplay between subject and filmmaker, and underscore key truths about investigative reporting: no-one is infallible, and no account of events should escape rigorous scrutiny. Outside the film’s remit—perhaps deliberately so—is how modern phenomena like social media, disinformation, and fake news further complicate the search for truth, and potentially empower authoritarian regimes to manipulate narratives. This omission is understandable: Cover-Up already carries a heavy load, and does an excellent job unpacking complex issues with clarity and urgency.