Julien Temple tells us about his Shane MacGowan doco Crock of Gold

Legendary music filmmaker pairs Shane MacGowan with yet more legends.

A new film by legendary music filmmaker Julien Temple (The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle) sees iconic Pogues frontman Shane MacGowan share stories from his life in conversation with other luminaries.

Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan is playing as part of Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival 2021. The film sees MacGowan in conversation with the likes of Irish republican politician Gerry Adams, Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie and Johnny Depp as he shares stories from his life, enhanced as you may expect from director Julien Temple by the extensive use of archival material and animation. Julien Temple joined us for a chat about Crock of Gold.

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY

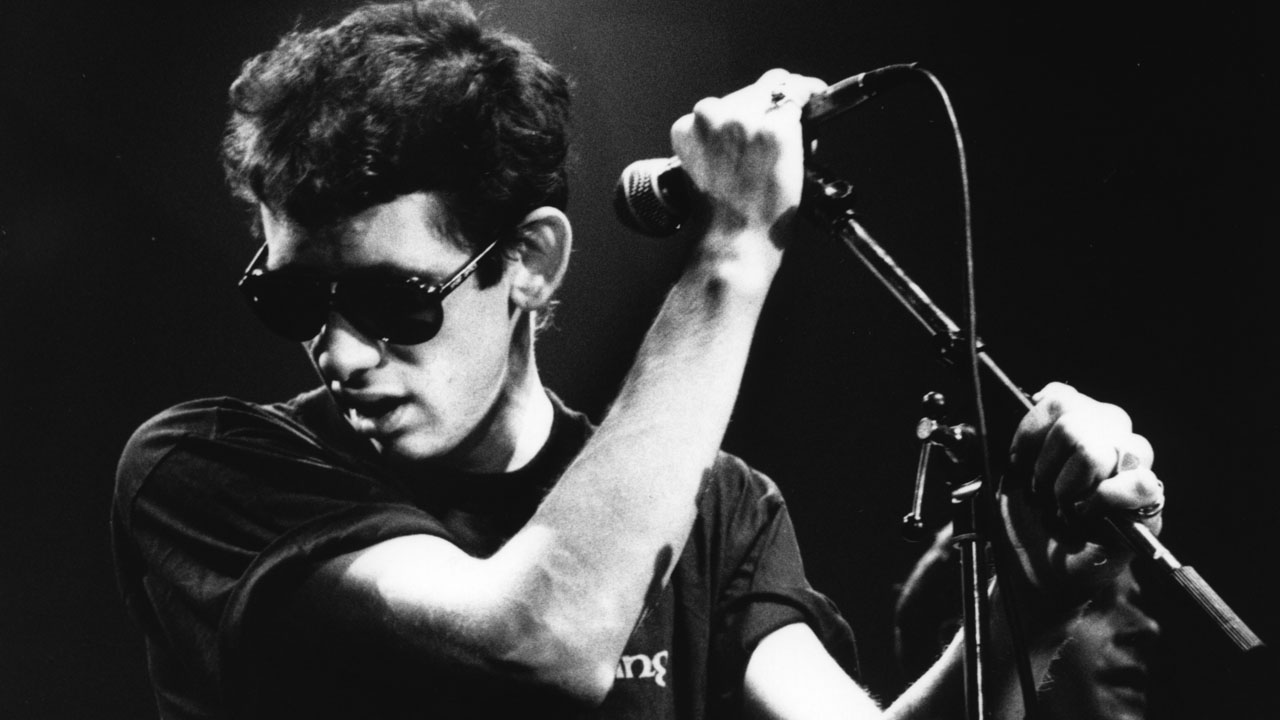

FLICKS: I’m curious about how far back your relationship with Shane goes, and how much of the footage we see of him up the front of punk gigs might have been yours?

JULIEN TEMPLE: Well, I did I did know him in those punk days and did the first interview with him, you know, that bit of footage where he’s talking, is something I shot. And then if you were at one of the gigs at the time, with your camera, when you’d be filming the audience you would always kind of settle on Shane.

Once Sid Vicious left the crowd and joined the band, the Pistols, Shane kind of became the focal point in the crowd, which was a very important part of the whole punk experience—the theatricality of the crowd being as important as the band really was. It was one of the most exciting things about it. So he was a very important punk figure in his own right. Long before anyone knew he was Irish or had anything to do with Ireland.

So for you to be making a film about him and his history and his experiences now, is that drawing on a long relationship of yours?

No, it’s just, you know, following him from afar and in the audience myself. I knew him at that moment. I saw some early Pogues gigs, but I didn’t stay in touch with him until making this film, which he asked me to do.

It’s a really interesting way to frame a life – across a series of conversations. Was there a particular reason why you approached it that way?

There was really, because after having asked me to do the film first, he said, “I’m not doing any fucking interviews”. “Fuck off, it’s your film—go and make it, I don’t want to be involved,” basically. An unusual approach, and a difficult one to take on board in some ways.

But you know, you realise after a while the problems that creates can open up ways of looking at things in a more interesting, exciting way and then trying to persuade him to take part in conversations rather than interviews with people, which is, another way of of trying to find out who he is. It’s a less precise way, but it’s a more spontaneous way, perhaps, than someone presenting themselves in a conventional interview. But it also gives you the added thing of getting a different Shane MacGowan each time, you know he’s a very different person with Johnny Depp than he is with Bobby Gillespie or certainly Gerry Adams.

So in terms of capturing the kind of many personalities of someone like Shane MacGowan, it’s a it’s a very interesting approach and I would really thank Shane for being difficult because it pushed you into things you wouldn’t have done otherwise, possibly, you know, so. I think the fact that people are difficult means they’re interesting, it’s another way of saying this is a fascinating person, you know?

Were there any chats that didn’t come to fruition or didn’t make the cut for one reason or another?

Oh, God, yeah. There were things we couldn’t say about many things that came out of that. The longest one was the Johnny and Shane one, which took all night and we had to go to bed at eight in the morning. This was on the third night—on the first night, I think Johnny didn’t turn up, on the second night I think it was Shane—so we’ve been staking out, hanging oiut for three nights, but on the third night they talked to eight in the morning, the crew had to go out to go get some sleep and when we woke up they were still talking the next day. So you couldn’t really stop them.

And there were many objects that just weren’t relevant to the film. I think they spent about an hour talking about Kris Kristofferson at one point. So it was it was hard to manage, you know? And you were kind of begging Johnny to hit some button that might get Shane talking about himself. But you know, Shane is an elusive snow leopard kind of character. He avoids the camera traps that people like David Attenborough might set up for him.

You weave in conversations that aren’t as contemporary, as those ones you’ve set up. To me, it adds an interesting layer to the film—to what extent these stories of his have come to define his character to an extent. Am I making something up there?

No, I think there is a way of looking at it as a Grimm’s fairy tale, you know—where you have an unreliable narrator, like many of the great stories. But to me, what Shane has created, this sense of who he is, that he’s worked very hard on over many years, is real to him. What did happen and what didn’t happen are fused in this extraordinary personality that he’s created. Some doubts and some element of boasting is part of the tradition of Irish storytelling, you know? So, you could make a film where you try and point out that what he’s saying didn’t happen, but to me, that would be disrespectful and missing the point because what’s unique and original about Shane is his sense of self and who he is and what he’s presented through his songs.

I think I’d much rather see Ralph Steadman illustrating a story of an episode in New Zealand than what I did today, which was read people trying to figure out if it had happened or not.

It’s part of who Shane is. Whether it happened or not, it’s fused in his mind with with who he is. So I think it’s important either way to understanding him, those kind of insights.

It is difficult at times seeing Shane’s physical condition in the film. How was that for you? There are times where you’re presenting him in a very unflattering light.

Well, you know, I was aware that I could only do that if he felt comfortable with doing it. He had asked to be filmed at this point, and he didn’t have a problem with being how he was on camera. I was keen to make as honest film as I could, and part of his life story is what he’s put into his body, you know, whether it’s drink or drugs, whatever. I think you shouldn’t shy away from showing that that does take a real toll.

It may have some benefits in Shane’s case, particularly in creative terms. But that’s another theme in the film. Certainly the film doesn’t recommend it, but it’s a theme that it doesn’t shy away from exploring. You know, whether that kind of substance use is important or necessary for his creative process.

What does it do to it? How intrinsic a part is it of it? You know, it’s part of the film, and you do want to try to make it clear that it has consequences—which his face and his body do show, don’t they?

He’s not being treated with kid gloves by the people that are chatting to him. Certainly, there’s a patience on the part of his interviewers, but I think that they are very conscious that they are in the presence of a fierce wit, even though even though the form has been dented at this stage.

I think that comes through, doesn’t it, that his intelligence and his wit and his ability to try and dominate space is undiminished. He’s very contradictory and made up of many different parts, I think, like most interesting people. There is a vulnerability to him. I think that’s masked by aggression. And hopefully, one of the things you get from seeing him in conversation with different people is you get an insight into different versions of Shane. He’s almost like a school kid with Gerry Adams, looking up to him. He’s very reverent. With Bobby Gillespie he’s got the old kind of gangster frights on someone you know, unfortunately for Bobby.

But with Johnny, he’s another character—kind of playing with another person’s fame in a way. They’re both very famous guys, so they have a strange shorthand playing with each other. You do see different versions of him—which you wouldn’t have got, I think, if you did a straightforward sit in this armchair, put a big camera in your face, start talking about your life kind of thing.

Another of the tough parts of the film the grind that Shane got put through on that gruelling, relentless tour—put in that position for someone else’s benefit. Do you think that can happen to the same extent today?

I think it does, like boy bands go through it, don’t they? There’s still rapacious exploitation in the music management business, I think. I mean, it’s certainly a thread that runs through the whole history of rock and roll, isn’t it? You know, I made a film about Dr. Feelgood, and it was a very similar thing. And it’s always the guy who writes the songs who suffers the most, because he doesn’t need to tour. All the others are all into it because it’s the way they earn money, but the songwriter probably doesn’t need to do it.

I get the idea it must be quite tough to be One Direction or 5 Seconds of Summer—boy bands like that. I think that exploitation is endemic still, probably.

What were some of the biggest discoveries for you in the process of making this film?

Well, one thing I would say is that we’re not really taught about English-Irish history and certainly not from an Irish perspective. So, researching Shane’s connection with the Irish independence struggle was very valuable to me. I learned a lot about Irish literature that I didn’t know. One of the things I like about making films is that it is a kind of continuing education. You’re learning on quite a deep level to make a film like this, you really have to get on top of the issues that you’re going to be immersed in and talking to people about.

I learned a lot of things that I didn’t know in terms of the English Irish that I didn’t know. How to survive making a film like this, was one of the important things I learned, because it’s quite easy to give up and sometimes think you aren’t necessarily going to be able to finish it.

Some of the techniques used to bring Shane’s stories to life are ones that you’ve employed before—like the use of archival footage and animation. Is that something that you conceive of from early on in the process or once you’ve started to see what your filmed material looks like?

Well, you do want to learn from the archive and the process of your immersion in things that you didn’t know before, so you don’t want to go in with too preconceived a plan. I think it’s good diving into it and not knowing where are you going to come up.

You know, I made a film called The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, where we kept running out of money. I had some friends who were studying animation so I could get them to tell bits of the story when we couldn’t afford to film it, for example. And I was finding I had to use Super 8 or VHS or whatever was around at the time to tell some parts of the story.

I realised that you can put things that shouldn’t really work together. And if it’s done with the right kind of idea behind it, you can create a continuum that makes sense, that doesn’t throw people out of the narrative momentum of what you’re doing, the story you’re telling. So, you know, it’s a thing I’ve used before, taking different formats and different things.

I was keen to use animation in a way that’s evolving through Shane’s life. So the animation in the 50s on the farm was inspired by the Orwell Animal Farm animation of that period; the Beano schoolkid thing in the 60s is from that comic book style; the R. Crumb hippie psychedelics of the late 60s, early 70s; the anime style when we see the band in 80s Japan… I was trying to use the different styles as part of the historical context of the journey that he’s he’s on in the film, you know?

As I alluded to before, seeing fear and loathing in a New Zealand hotel has a very specific vibe to it.

Yeah, well, Ralph Steadman is the man for fear and loathing. And Ralph is a friend of Johnny’s so, you know, we were lucky to have to have him involved on that particular piece. And again, it’s a very vivid moment of Shane MacGowan storytelling, so it would be very hard to shoot that. It’d be very expensive to do it convincingly, so Ralph Steadman gives you an immediate in to the psyche of what’s going on at that point, you know?

Did this stir anything up for you personally as you looked back through someone’s stories about their life?

Well, you always have a sense of having lived through the same period as someone like this or Joe Strummer or Wilko Johnson—so there’s aspects of, you know, traveling the journey you’ve travelled in this space of time in your life. So, yeah, you do understand your connection with your time on the planet a little more precisely each time you do one of these films in a weird way.

This doesn’t feel like an epitaph for Shane, but it’s possibly one of the last things that we’re going to hear from him, in his own words. Was was that an important thing for you to respect in making the film?

Well, I believe he’s capable of surprising us. I wouldn’t write him off, so I know I didn’t feel it was his last word. Maybe it will be, but I think as the film shows, he’s still there mentally and, you know, hopefully will surprise us, and do something else.

Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane MacGowan