Monsieur Aznavour is refreshingly different: a biopic that emphasises hard work

A biopic that focuses on craft, commitment, and growth rather than a magically gifted protagonist.

Monsieur Aznavour, which depicts the life of singer-songwriter Charles Aznavour, defies biopic clichés by celebrating discipline and ambition over mythical musical destiny, writes Luke Buckmaster.

We’ve seen it a zillion times: biopics about phenomenally talented musicians who are kissed by the gods, their destiny written in the stars, their fame and fortune a fait accompli.

Monsieur Aznavour—a very enjoyable film about French-Armenian singer-songwriter Charles Aznavour—isn’t one of them. Writer/directors Mehdi Idir and Grand Corps Malade posit a different kind of thesis: that success is about good ol’ fashioned hard work. All artists require talent to make a splash in the zeitgeist, they seem to be saying, but it’s sheer effort and devotion that pays dividends.

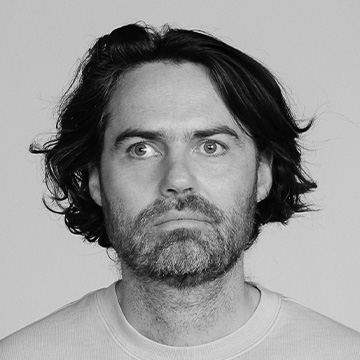

The crooning protagonist, played charmingly and with an air of aloofness by Tahar Rahim, was once described by music critic Stephen Holden as “French pop deity,” identifying his enormous reach and status in French culture. The film tells us this was no inherited throne, depicting Aznavour as a laser-focused professional with a refreshingly methodological approach to realising his dreams.

In one scene, Aznavour identifies his weaknesses and plans accordingly. He believes he needs to be more cultured, more exposed to great art, so he resolves to gorge on classic literature. He can’t change his raspy voice, he reasons, but he can work on a more developed range. Scenes like this, which view the fulfillment of legend as a series of actionable points, are rare in musician biopics, a genre that depicts people devoted to their art and craft, of course, but often gilds the lily and perpetuates the lie—however well-intended—that the greatest talents always rise to the surface.

This film’s trajectory is more inspiring, with a message to chase success—and never believe it’s going to land in your lap. At the same time, the protagonist is clearly naturally very talented as well as confident, borderline cocksure. In one scene with his early collaborative partner, Pierre Roche (Bastien Bouillon), Aznavour comments on how easy it is to write lyrics—the kind of line, so candidly dropped, that would turn lesser capable artists green with jealousy, like Salieri observing Mozart in Amadeus.

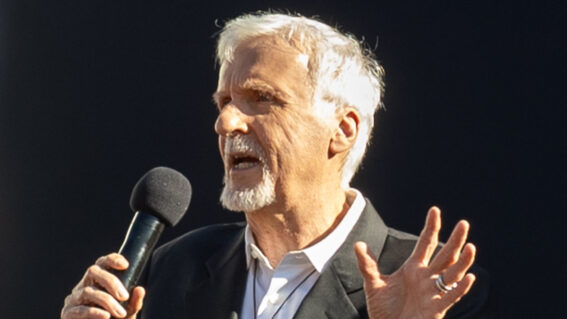

Just as, in Monsieur Aznavour, the artist is devoted to his work, this film is devoted to the artist, with only a couple of other interesting characters in relatively small roles. Pierre, with whom Aznavour bluffs his way into a cushy club gig, is one of them. The other is Edith Piaf (a fun, prickly Marie-Julie Baup) who recruits Aznavour as a supporting act and becomes a mentor-like figure, insisting—in response to his desire to crack the American market—that he “must sing your songs for a French audience.”

The subject’s work ethic reminded me of a lovely moment from The Shawshank Redemption, in which Tim Robbins’ erudite prisoner, Andy Dufresne, finally gets a shipment of books and a cheque sent to him by the state, for his library, after writing a letter a week for years. His response is not to bask in the glow of his achievement, but to increase his efforts, and double down: “from now on I’ll write two letters a week instead of one,” he says.

Monsieur Aznavour, like James Mangold’s recent Bob Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown, avoids silly light bulb moments that attempt to illustrate the seeds of genius blooming right in real-time. In one scene, Avnavour recognises that “each word has its own rhythm,” which feels like a level-headed way of articulating his approach: considered, insightful, self-analytical. In another, he gets carried away, shrieking: “I’ll write a song a day! I’ll sing until I rip my throat!”

In A Complete Unknown, Mangold faced a different problem. Freakishly great, surreal prose like Mr Tambourine Man or Like a Rolling Stone cannot be presented as an issue of merely working harder. But Mangold obviously didn’t want to do the “touched by the gods” thing either. So he settled on depicting Dylan as being almost pathologically devoted to his craft. I say almost, because, in A Complete Unknown, Dylan can’t help but strum, write and sing, as if his guitar and notepad were extensions of his body. Writing and playing are as ingrained in his daily life as showering or eating. Aznavour consciously works harder, pushes himself to the brink.

Notably, neither film portrays their protagonists as happy, or even content, despite achieving stratospheric success. Both get concert scenes in front of rapturous audiences, of course, but they come with a melancholic tang. Are these men chasing something they can never catch? Are they even capable of pausing, exhaling, appreciating the present? One thing that can’t be questioned: their work ethic.