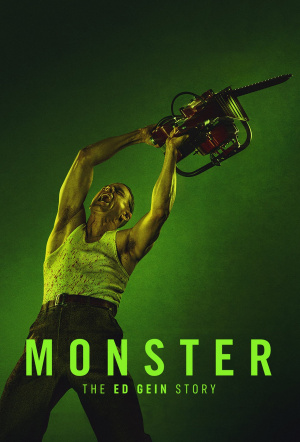

Monster: The Ed Gein Story tries to make him the victim of our voyeurism

The big, fat irony here is that at no point does this exploitative show address its own complicity in the bloodlust it blames Hollywood for.

Monster: The Ed Gein Story is exploitative, trashy, and entirely your fault. Certainly, it’s among the more unusual television theses presented this year, and sort of fascinating in its own wrong-headed way. Gein confessed to the murder of two women, Mary Hogan in 1954 and Bernice Worden in 1957. He was also found with a home full of corpses—exhumed from local graveyards, mutilated, and fashioned into clothes and pieces of homeware.

The Ed Gein Story, however, presents him as essentially the Platonic ideal of the serial killer, since corrupted by every post-war horror humanity has conjured up and broadcast widely, making us all (and no one is spared, save the show’s makers) more ravenous for violence and morally unsalvageable.

Related reading:

* House of Guinness blends sex and desire with Ireland’s most famous export

* Gen V hasn’t lost its teeth but, like The Boys, is feeling less “anti-comic book”

This stems from the theory that Gein, unlike the subsequent serial murderers who claimed him as their idol, the Ted Bundys and Jerry Brudoses, found no pleasure in his sadism. I’ll leave that to the psychologists and moralists to verify, but in Ian Brennan’s world (Ryan Murphy’s frequent collaborator has been credited here as sole creator, so I’ll portion all the blame to him) that’s the only licence needed to both romanticise and sexualise Gein, while also somehow making him the victim of our own voyeurism.

You’ve barely had the chance to breathe before Gein, played by Charlie Hunnam, is butt-naked with chiselled abs on full display, or engaged in a relationship with a young woman named Adeline Watkins (Suzanna Son), who despite being a real person is here falsely presented as his twinned soul in the realm of morbid curiosity. He’s also, especially in the later episodes, presented as a puppy-eyed naïf desperate for redemption. Hunnam does exactly what’s asked of him, and performs earnestly, even if he’s made Gein sound (for some reason) like Winnie-the-Pooh.

I’m not averse to the way these Monster seasons, have ironically, repudiated the label “monster” in order to remind us that those who commit the unthinkable are still human, at the end of it all. We help no one by distancing ourselves—only by sitting with the uncomfortable can we start to reshape society in a way that’s equipped to prevent these crimes before they even happen. But the series is also hardly engaged in the hard work.

The wider point, I guess, is that Gein has been appropriated not only by subsequent killers, but by artists who have rewritten his deeds to suit their own narratives, from Alfred Hitchcock to Tobe Hooper to Jonathan Demme (though the latter isn’t even mentioned, despite the homage to The Silence of the Lambs). And with each new version of the myth, the audience’s bloodlust grows—supposedly.

Now, it doesn’t really matter what’s fact and what’s fiction. Who cares if Brennan depicts Gein chasing down two hunters (possible) with a chainsaw (false and entirely Hooper’s invention for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre).

Who cares if he uses a ham radio to contact Nazi war criminal Ilse Koch (Vicky Krieps, a surprising addition to the Murphyverse)—”The Bitch of Buchenwald” as the show calls her, who allegedly crafted keepsakes out of the skin of Holocaust victims (false and framed as a hallucination, though Gein did seem to develop a fascination with Koch, specifically as she was depicted in pulp magazines).

Who cares if the show introduces the real-life counterparts to the FBI profilers of Mindhunter so that Gein can help them catch Ted Bundy (entirely false, and again presented as a hallucination).

Brennan happily damns Hitchcock, Hooper, Demme, and (I guess?) Mindhunter’s David Fincher, with Hitchcock (Tom Hollander) slipping into a cinema post-Psycho and being horrified that the audience are all laughing like hyenas at a scene of sexualised torture. “The audience has changed and I’m the one who changed them,” he laments. Psycho, and Gein’s crimes by extension, burst the violent psychosexual dam, so we’re told.

And yet, the big, fat irony here is that at no point does The Ed Gein Story address its own complicity in all this. You spend all eight episodes waiting for that metatextual turn, that possible Murphy or Brennan cameo, and instead it’s scene after scene of every Gein rumour depicted as explicitly as possible, alongside some deeply insensitive invocations of the Holocaust.

Even the Psycho shower scene is recreated without the sly cuts away from the nudity and gore. All while Gein himself turns around and points at us, the audience—or, in one case, a cruelly invoked Anthony Perkins (Joey Pollari)—to say “you’re the one who can’t look away”.

This ends in a truly bizarre scene in which Gein, in the psychiatric hospital where he spent the rest of his life, talks to a sympathetic nurse (Meighan Gerachis), who urges him to tell his life story, since the others “added things that weren’t real, taking out things that were horrible” (and by this she means his abusive and fervently religious mother, played by Laurie Metcalf). He replies: “I think enough people have told my story.”

Alright, then—so what have I been watching for the past however many hours?