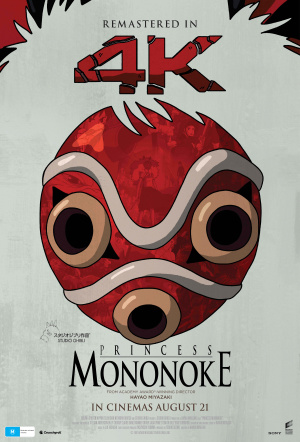

Princess Mononoke and 28 Years Later might be 2025’s best double feature

As Princess Mononoke makes its way back into cinemas, Liam Maguren writes on the themes and allegories it shares with Danny Boyle’s recent big-screen release.

A couple of months ago, I caught Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later in cinemas. A day later, I rewatch my Blu-ray of Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke. Little did I know how potently they’d match as a double feature.

They seem like polar opposites at first. Miyazaki depicts an historical fantasy world with warring factions and nature spirits while Boyle belts out an alternate near-future England quarantined from the world where a barricaded community of survivors ward of zombie-like infected people.

But as much as I would love to decree, “It’s this year’s Barbenheimer,” that wouldn’t be truthful. Like a night of cakes and cigarettes, the 2023 phenomenon celebrated the glaring differences between box office titans Barbie and Oppenheimer—one’s a festive celebration of an iconic doll, the other’s a hard-edged biopic on the man who made the atomic bomb. Princess Mononoke and 28 Years Later, on the other hand, pair like a bow and arrow.

Princess Mononoke

28 Years Later

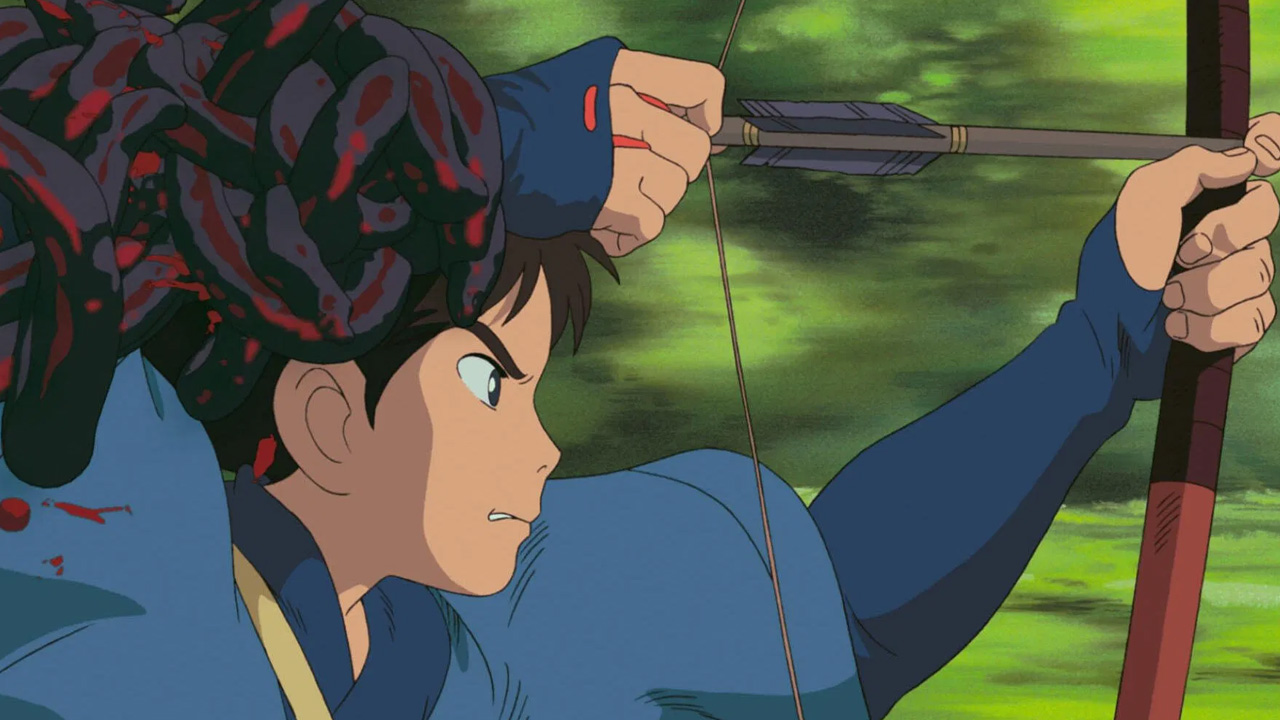

Both films tell tales of young men forced to venture outside the safety of their community. Princess Mononoke’s Ashitaka is afflicted with a deadly curse and, thus, banished from his village. To cheat death, he searches for an elusive forest god, only to discover a vicious war waged between an industrial clan and the spirits of nature. Spike from 28 Years Later also ventures into the wild in search of a doctor and a cure—not for himself, but his unwell mother.

While Ashitaka might be more confident and combat ready than Spike, both adventurers are similarly out of their depths in these unfamiliar worlds. Reasoning with a bloodthirsty wolf lord feels as tense as running from a butt naked alpha zombie.

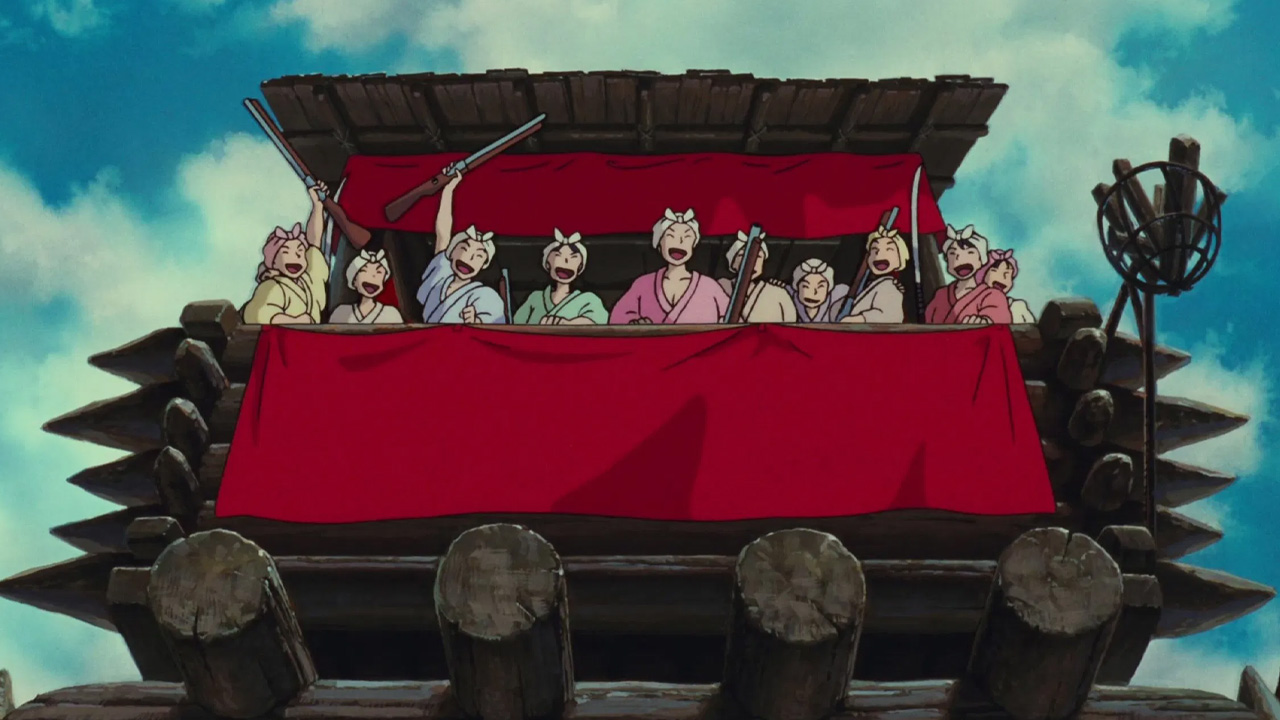

Both films also emphasise the strengths of a community. Miyazaki shows this with the women powering Iron Town, former brothel workers turned Rosie the Riveter thanks to their boss Lady Eboshi, while Boyle spends a good third of his movie relishing in the culture within Spike’s fortified home, which could easily be mistaken for a 1980s British village.

Princess Mononoke

28 Years Later

But a happily united people can also house darkness. For Spike, his rite-of-passage celebration felt unearned, with his boozed-up pa making bold-faced lies about his son’s bravery in his first hunting trip. You get the feeling this place hungers for such myths about growing strongmen, as if that secures the village’s longevity. Similarly, the people of Iron Town blindly follow Eboshi’s war against the forest gods, unaware of the imminent destruction hurtling towards nature and themselves.

Ashitaka and Spike, meanwhile, encounter people who have embedded themselves in the environment they’ve been taught to fear. Mononoke herself has been raised by a wolf god and knows the ways of the wild while Dr. Kelson replaces fear of the infected with an infectious curiosity, which lends to his preservation.

I realise I’m playing connect-the-dots with the storylines here, which can come across as coincidences masquerading as insight. But these are necessary details to fully understand the powerful thematic cross-stitching that makes this a great double feature.

Both films give you a lot to mentally chew on. Watching them side by side, however, the idea of detachment becomes more pronounced. Specifically, detaching from society to better understand the surrounding world.

Neither film suggests we abandon civilisation outright. Rather, they reveal how the comfort of community often lies within a bubble of ignorance. For Ashitaka and Spike, their circumstances force them out of their comfort zones and into the wilds where they must adapt to survive.

They’ve been rightly taught by their communities to be cautious of dangerous beasts like woodland gods or herds of infected. But knowing a creature only through fear and danger means never knowing it completely.

Princess Mononoke

28 Years Later

Ashitaka’s banishment from his village puts him on the path to finding the feared wolf-god, a big beast that constantly threatens to kill him but also has an adopted human daughter who she loves. Spike’s choice to flee his village with his mother sees him in constant danger with the infected, but the pair’s run-in with a pregnant one also leads to a worthwhile discovery.

In both instances, the leads discover a softer side to the creatures known in their communities as terrifying threats. While that’s true, it’s not the only truth. When our leads learn this, they grow in a way their peers back home do not.

That’s not just a reality in these two movies; that’s the reality of humanity’s relationship to nature. Tarantulas are a source of pure terror, even though they’re pretty chill creatures. Bruce Wayne turned the bat into a symbol of fear, despite them being really great for growing bananas and chocolate. Jaws taught us to look at sharks like monsters, when they’re really more like dogs.

There’s more to be said about our displacement with nature and the need to venture out of our bubbles but it’s best to discover these conversations within these films on your own terms. Earning decent box office earlier this year, Boyle’s trilogy-maker recently hit streaming rental services. Originally released in 1997, a 4K version of Miyazaki’s masterpiece has just reappeared in cinemas… 28 years later.