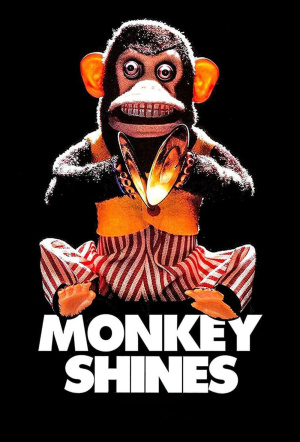

Retrospective: Monkey Shines is still the greatest evil monkey movie

In the lead-up to next year’s creature feature Primate, we celebrate George Romero’s 1988 horror classic—the only evil monkey movie that truly earns its bananas.

We don’t know exactly what cultural and political events will rattle the earth’s tectonic plates next year, though we can be sure of some things: wars will rage, American democracy will teeter on the edge of a cliff, and Hollywood will release a new evil monkey movie. This is, admittedly, not a burgeoning genre. But the very positive buzz surrounding Primate—which is about a chimp that contracts rabies and, for reasons that amount to either science or just extreme crankiness, goes on a hysterical murderous rampage—got me thinking. Even if this film is good, could it really be as good as Monkey Shines?

This under-rated jewel in the sadistic simian crown was released in 1988 and directed by horror auteur George Romero, best-known for his Night of the Living Dead franchise. It is indeed about a monkey; I suppose you could call it a creature feature, though it’s much more than that label implies. Creature features usually involve a violent, salivating animal mindlessly sending a bunch of unfortunate humans to the great beyond: biting ’em, slashing ’em, killing ’em, and generally being unpleasant.

There’s certainly an element of that in Monkey Shines, which Romero adapted from Michael Stewart’s novel of the same name. But the perverse primate in question, a helper monkey named Ella, clearly has a brain—and discriminates between the people she kills. She’s emotionally needy, even, dare I say it, emotionally complicated, even if one doesn’t turn to this film for profound insights into human or simian mindsets.

The amazing thing about Monkey Shines is that it has all the hoofprints of a throwaway B movie, yet somehow emerges as a work of red-hot psychological intensity. No film that deploys a mad scientist, animal POV shots, and a murderous monkey who is psychically connected to the protagonist has any right to feel this emotionally real.

That protagonist, Allan, is quickly established as the kind of exercise fanatic who begins every morning stretching like he’s participating in an ESPN special, before going for a run wearing a backpack full of weights. He may be annoyingly fit, but we wouldn’t wish on our worst enemy what happens to him next: Allan gets struck by a vehicle (or, as his doctor puts it, “creamed by a truck”) and becomes a quadriplegic. He understandably struggles, loses the will to live, and even attempts suicide—the latter depicted in a chilling moment that demonstrates Romero’s ability to crystallise emotional horror into a single unshakable image.

Enter Ella! She’s here to help—at least initially—and does a bang-up job assisting Allan. What Allan doesn’t know is that his friend Geoffrey (John Pankow), who gave him the monkey, is also a bit of a mad scientist (something to put on his LinkedIn profile?) who’s been experimenting on her with mysterious serums. Trouble begins when Ella starts to feel resentment toward Melanie (Kate McNeil), a specialist in helper monkeys with whom Allan develops a strong and potentially romantic connection. Ella’s presence also creates issues—to put it lightly—with Allan’s carer, Maryanne (Christine Forrest).

This is highlighted in another scene that taps into a deeply uncomfortable kind of horror—not the sort usually associated with B movies. After a bitter altercation between Allan and Maryanne, resulting in the latter storming out of his bedroom, Maryanne’s pet budgerigar flies onto Allan’s face and vigorously pecks at it, going straight for his eyes. Alone in the room, all he can do is cry out for help while Ella watches on, trapped inside her cage, jumping up and down, wishing she could do something and presumably plotting the budgie’s grisly demise.

During this very unsettling scene, it dawned on me, while rewatching the film recently, that the psychological intensity of Monkey Shines is cross-species, in this instance involving two humans, a monkey, and a bird. Everybody—every creature—has their own motivations and competing agendas. They intersect in spectacularly hideous ways, culminating in one hell of a finale, which delivers another unforgettable image, the film’s most unforgettable image, not to be divulged here.

There’s lots more going on. For instance, the psychic connection between man and monkey results in the latter acting out the former’s wild impulses—the sort of wicked fantasies one may fleetingly entertain but would never carry out oneself, unless one were a complete psycho. Like the monkey. Romero stirs all of this together with a devil’s grin and brings a lithe, disciplined approach to storytelling, the pace brisk and the energy crackling. Primate has a high bar to clear.