Shelf Life #13

Aaron serves up another trio of under-recognised films in this lucky thirteenth edition of Shelf Life. From a canine murder suspect to some culty weirdness and a film that audiences apparently had to sign an anti-spoiler waiver before seeing, these films might just encourage you to step out of the sun, draw the blackout curtains […]

Aaron serves up another trio of under-recognised films in this lucky thirteenth edition of Shelf Life. From a canine murder suspect to some culty weirdness and a film that audiences apparently had to sign an anti-spoiler waiver before seeing, these films might just encourage you to step out of the sun, draw the blackout curtains and wile away the day in front of your flickering screen…

THEY ONLY KILL THEIR MASTERS

The final film shot on MGM’s backlot before it was sold and the sets bulldozed, James Goldstone’s Chandler-esque mystery They Only Kill Their Masters (1972) probably isn’t on anyone’s radar for re-appreciation, but it might pique the interest of excavators of odd ‘70s studio curios due to its canine protagonist, a doberman named Murphy who’s thought to be the culprit behind the body of a woman washed ashore a small coastal Californian town.

James Garner plays Abel Marsh, the police chief who’s a little peeved to have returned from a week-long break to be saddled with investigating the case, which as it turns out, isn’t Murphy’s fault. In between closely escaping an arson, stopping a bar fight, quizzically deliberating over nudie photos and getting drugged by dog-prostate-meds, Marsh also has to reluctantly babysit Murphy and put up the county sheriff (Harry Guardino) poking his nose where it doesn’t belong.

They Only Kill Their Masters isn’t as fun as the endearingly ridiculous The Doberman Gang from the same year, but Garner’s easy to watch as the “city folk”-hatin’ Marsh, his laid-back mystery-solving skills amusingly suggesting indifference and ineptitude as he appears to be more consumed by bedding Katherine Ross, who isn’t given much to do but play pretty as Hal Holbrook’s vet assistant-turned-suspect. The film definitely has a TV-ready flatness about it: Goldstone’s extensive background on the tube (The Fugitive, The Outer Limits) shows in his functional but thoroughly bland visual style, making this occasionally seem like a lost episode of Garner’s later show The Rockford Files.

Nevertheless, Lane Slate’s script flirts with a few risque elements — “shocking” revelations of lesbianism and group sex! — while elsewhere it goes for tasteless, tone-deaf, politically incorrect exchanges, like Garner saying offensive things like “I’m a faggot”, and a cop enjoying a hearty chuckle over a case of a woman who got her nipple bitten off. The supporting cast features a bunch of seasoned Hollywood old-timers such as Arthur O’Connell (Anatomy of a Murder), Edmund O’Brien (D.O.A.), Ann Rutherford (Gone with the Wind) and June Allyson (Little Women), all adding colourfully eccentric qualities to their roles as the town’s locals.

MYSTERIOUS TWO

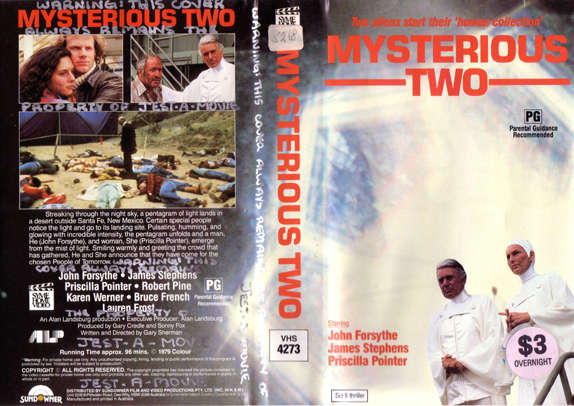

The bizarro true story of “Bo” (Marshall Applewhite) and “Peep” (Bonnie Nettles) — the pair behind the UFO cult Heaven’s Gate which led to the mass suicide of 39 people in 1997 — could do with some form of definitive cinematic representation, but to date there haven’t been too many attempts to bring it to screen (Louis Theroux once tried to contact the group for his BBC 2 series Weird Weekends).

In 1982, there was The Mysterious Two, an appropriately weird TV movie from writer/director Gary Sherman (of genre favourites Dead and Buried and Raw Meat) who shot it in ‘79, initially intending it to be a pilot for a show that never materialised. Apparently Applewhite served as an uncredited advisor; either way, it’s likely that he would have approved the final results, since Sherman seems to have effectively tapped into whatever spaced-out wavelength he was on.

Simply referred to “He” and “She” in the film, the celestially-outfitted Bo-and-Peep characters are played by John Forsythe (Charlie’s Angels) and Priscilla Pointer, who first turn up at an abandoned missile silo, then begin to recruit folk from all over the US to join them for “The Event”, which involves the promise of interstellar travel to a better life. Not everyone is fooled by their quasi-spiritual mumbo-jumbo (“Shed your earthly possessions!”) though, and they intend to do something about it, including Tim (James Stephens), a hippy flautist whose girlfriend has joined the cult, Sheriff Virgil Molloy (Noah Beery, Jr.) and his deputy Boone (Robert Englund), and persistent, headline-chasing reporter Ted Randall (Vic Tayback).

As a look into the influence of false prophets, The Mysterious Two is occasionally disturbing, especially during an eerie, blatant callback to the still-fresh Jonestown massacre of ‘78. However, the chintzy optical visual effects, awkwardly inserted voice-overs and seemingly unfinished storytelling prevent the film from achieving its narrative ambitions — but not disastrously so. It’s still an absorbing watch, particularly if you’re fascinated by the subject matter, and the score, alternating between minimal flute cues and droney sounds, has a hypnotic, late-night vibe that reels you in.

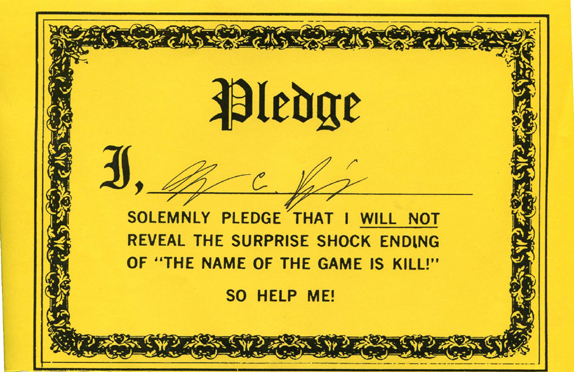

THE NAME OF THE GAME IS KILL

I’ve been wanting to see this thriller from the Sick Sixties for years (you don’t forget a title like that), but it was pretty hard to come by until VCI released a special edition DVD earlier this year. I’m pleased to say that it didn’t disappoint and I lapped up every psychotic minute. No game is actually declared “Kill” in the movie — its other title The Female Trap is perhaps more accurate, though hardly as awesome — but writer Gary Crutcher supplies just enough twisted shenanigans to warrant its lurid title.

Jack Lord (Hawaii Five-O) is Symcha Lipa, a Hungarian drifter who gets picked up by Mickey Terry (Susan Strasberg) in the middle of the Arizona desert. She offers to take him back to her house — a grubby gas station — where he’s soon acquainted with her family: mum Mrs. Terry (T.C. Jones), and her two sisters, the elder Diz (Collin Wilcox Paxton) and younger Nan (Tisha Sterling), whom when we first meet, has just been expelled from school for lighting a cat on fire. Uh-oh.

I won’t say too much for fear of ruining some of the plot’s finer demented pleasures, but I will mention that the Terry’s don’t have a great track record when it comes to men and leave it at that. If you like shock endings, The Name of the Game is Kill has an outstanding one that surprisingly knocked the wind out of me. One of the earliest movies shot by celebrated cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (Close Encounters of the Third Kind), who contributes a visual sheen that makes the film seem less schlocky despite its ragged production values.