Sisters with Transistors director on her doco about the pioneers of electronic music

Lisa Rovner’s doco explores ten pioneering, yet undersung, women in the history of electronic music

The story of electronic music’s female pioneers is told in Sisters with Transistors. Rachel Ashby spoke with Lisa Rovner, director of this fascinating doco playing at the Wellington leg of Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival between November 10 and 20.

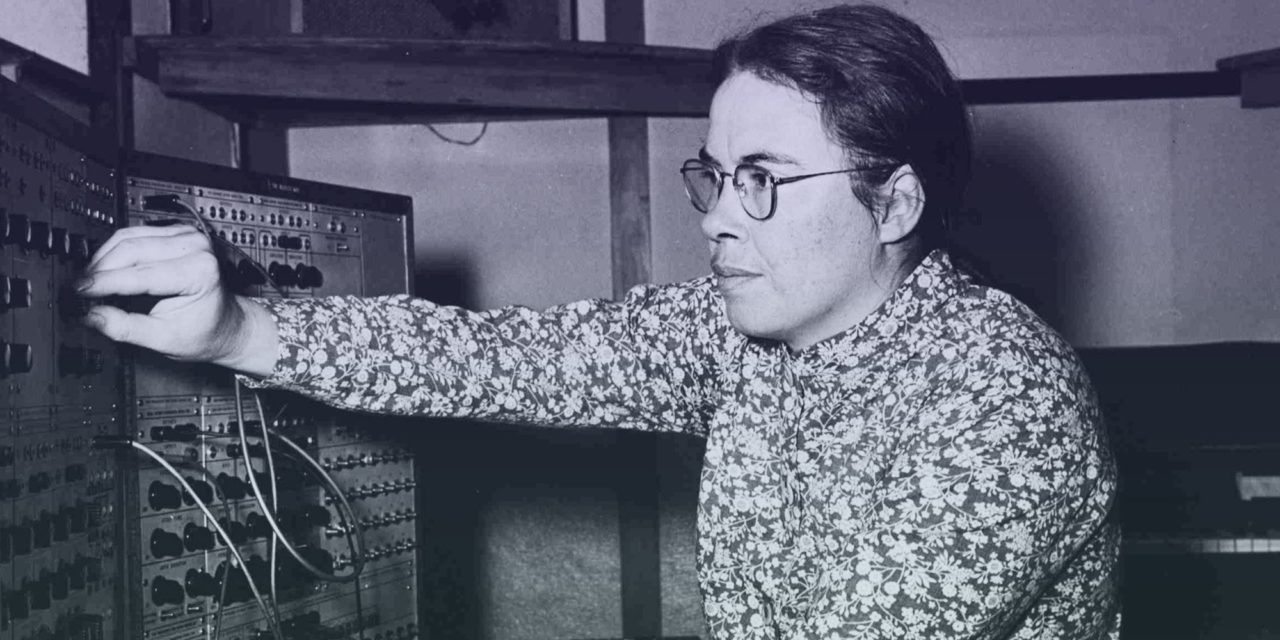

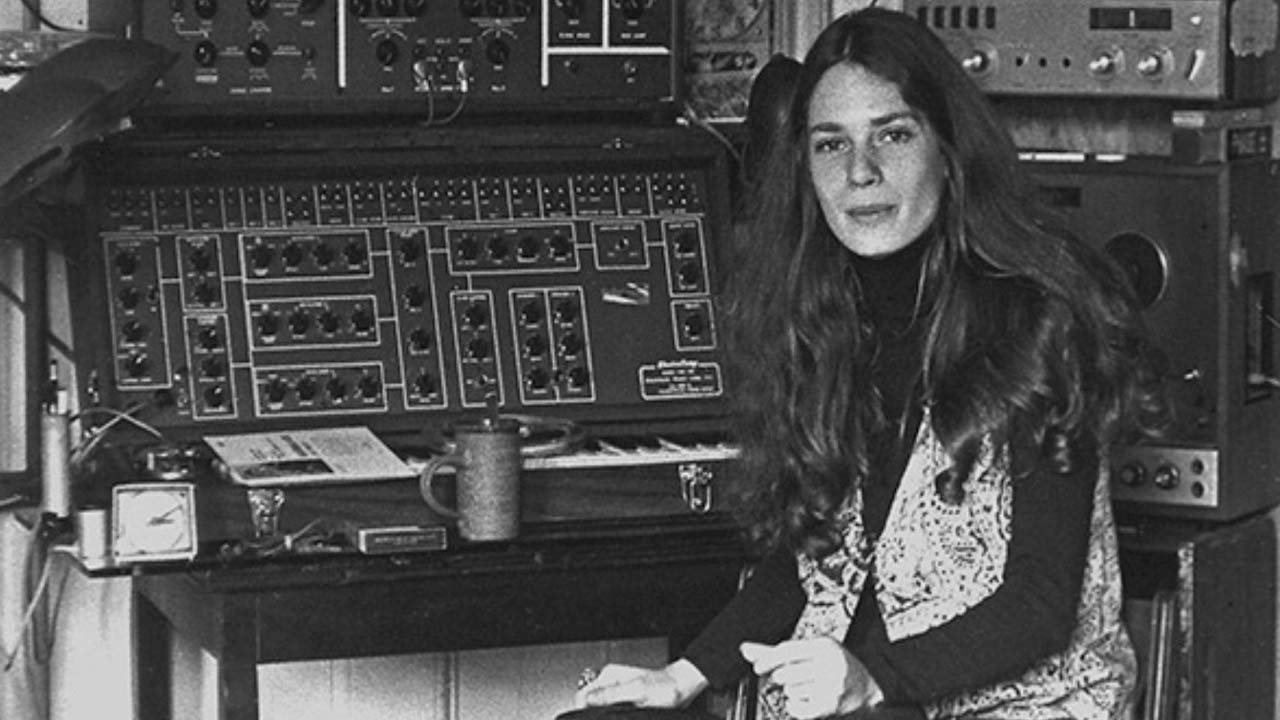

Lisa Rovner’s Sisters with Transistors highlights the stories of ten pioneering, yet undersung, women in the history of electronic music. Through lush archival footage, the technical and conceptual innovations of artists such as Laurie Spiegel, Suzanne Cianci, Pauline Oliverios, and Delia Derbyshire are brought into the foreground of the canon and given space to prove their invaluable role in shaping the sounds of music today.

Narrated by the indomitable multi-media artist Laurie Anderson, the film avoids didactic talking heads and instead opts for thoughtful and open-ended voiceovers to create a counter-narrative to often told stories of male invention and creative vision.

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY

FLICKS: There are a lot of amazing women in this documentary, and there are some incredible stories of innovation in this film. What was your first introduction to these artists?

LISA ROVNER: I guess my first introduction was Laurie Anderson when I was seven years old. That kind of changed my life in a way. I had also heard of Delia Derbyshire and I had heard an Éliane Radigue record at a friend’s place, but I didn’t quite realise who they were or what they had made.

I think it wasn’t until I saw an article that had all of these women who had been left out of the canon in one place that the scale of it struck me. I think I had always thought of early electronic music as a male pursuit, so it was just incredible to discover that from the very beginning women have been integral to inventing the devices and techniques that would define the shape of sound for years to come.

I studied politics so I’ve always been really interested in the politics behind storytelling: the stories that we are told, the stories we are not told, and the consequences of that. In a way, I think all of my work revolves around confronting dominant narratives with counter narratives. This story grabbed me both visually and sonically, and through the bigger political story of how this new technology really enabled women to be composers.

Why did you decide to include so much footage of the technical process of music-making in this film?

I was just blown away by seeing them work. I really had no idea how electronic music was made, especially the early kinds, so I was just keen on showing it. I discovered these archives and I just thought ‘oh my gosh, this is just the most mind-blowing process’.

It’s just so incredible to think how electronic music really opened up the idea of what music is to the entire field of sound. These composers really re-imagined music and pushed its boundaries to include all kinds of noise.

What we discover in the film is music without melody—it is music made from circuits, music that was made from lampshades—and I just loved that. I loved being able to show how this music was being created.

Watching the film, I found it very empowering that these women knew what they were making was important and radical, despite the indifference of some of their male peers and the contemporary music establishment. Was this something that you were struck by when collating this material?

Yeah, definitely. Although, I do think that they also had support from some of their male counterparts. I think if anyone is to blame for why we don’t know these women, it’s our storytelling practices rather than particular individuals.

Of course there are also moments in the film where, for example, Élaine Radigue talks about being valued in the studio because she “smelled good”. Overhearing a comment like that is just so sad and funny—all of these things at the same time.

But I do think that the real culprit is ultimately storytelling. When we write these narratives we are often searching for a sole hero who’s generally white and male, so it was really important to me that I told this story in a feminist way. We wanted to feature multiple heroines to draw connections between and we also wanted a narrator that’s not all knowing.

My hope with this documentary is to create curiosity so that people don’t walk away thinking ‘Okay, now I know the history of women in electronic music’. This is just the beginning: there are so many more women that didn’t feature in the film for different reasons.

There has been some criticism that the film has a Eurocentric focus in the subjects chosen, was that due to archival limitations?

It was an archival issue, it was a budget issue, it was a language issue. I never intended for this film to be interpreted as the comprehensive history of women in electronic music. There are diversity limitations in this project because I didn’t have the budget to travel around the world or to hire translators. I reached out to a number of institutions and never heard back.

Because I didn’t have something like Netflix behind me, it was very difficult to even make this film, and to find this archive. It really was a passion project.

Also, the research is still coming out—it’s exciting! I heard a BBC radio program just a few weeks ago about an early Moog synthesiser that had been in India. When I was doing the research for the film, that story hadn’t even been published yet.

So I guess I go back to wanting to incite curiosity with this film. I don’t want people to think that this is it—that these are all the women in electronic music.

What was the process of tracking down the archival footage for this film like?

Originally when I first started thinking about making this film I thought I would hire an archivist and get the research going. But ten days and two grand later, we still had nothing because it turns out this material was kind of hidden. So I took on the challenge myself and started contacting universities where someone may have done a lecture, and I would end up getting passed on to other universities and so on.

It was so different for every woman. For some of the women the archive was much more straightforward. For example, the Delia Derbyshire archive was all held by the BBC. But with Pauline Olivierios, some of the most beautiful footage I have of her was actually filmed by her partner at the time. I just happened to reach out to the brother of the partner, and it turned out he had recently finished digitising that Super 8 film.

It was such a wild adventure. The film took many, many years to make, and it was so difficult; some of the archive only came through in the final stages of completing the film.

Laurie Anderson’s open-ended and poetic style of narration draws the film together so well. Did you always envisage Laurie Anderson being the voice for this film?

I knew I wanted her to be part of the film from very early on, but I wasn’t convinced that it made sense to include her as one of the subjects because she was somebody that I had known about since I was a kid. So, although I still don’t think people recognise just how important and groundbreaking she is, she was not exactly ‘unsung’ like the other women.

In the end we wrote a voiceover for her and waited until we had a rough cut of the film to ask her to be involved. Her enthusiasm for the project was immediate and I can’t begin to express how happy I was when she agreed. I’ve always been super inspired by the way she talks about politics in this very disarming and entertaining fashion. That’s exactly what I hope the film does.

What do you hope people take away from watching this film?

The main thing is I just want it to inspire people. I feel like the world is so dark and sad and we just really need more inspiring stories. I guess the thing that I’ve learned through the making of this film is the importance of active listening, and listening especially for what is being left out.

I think of Pauline Olivieros’ philosophy of ‘Deep Listening’: she really believed that listening was a form of activism and that through deep and inclusive listening we could heal. I hope that people will walk away from the film with this notion that more listening is needed to heal.