Netflix drama Steve breathes new life into the ‘school of hard knocks’ genre

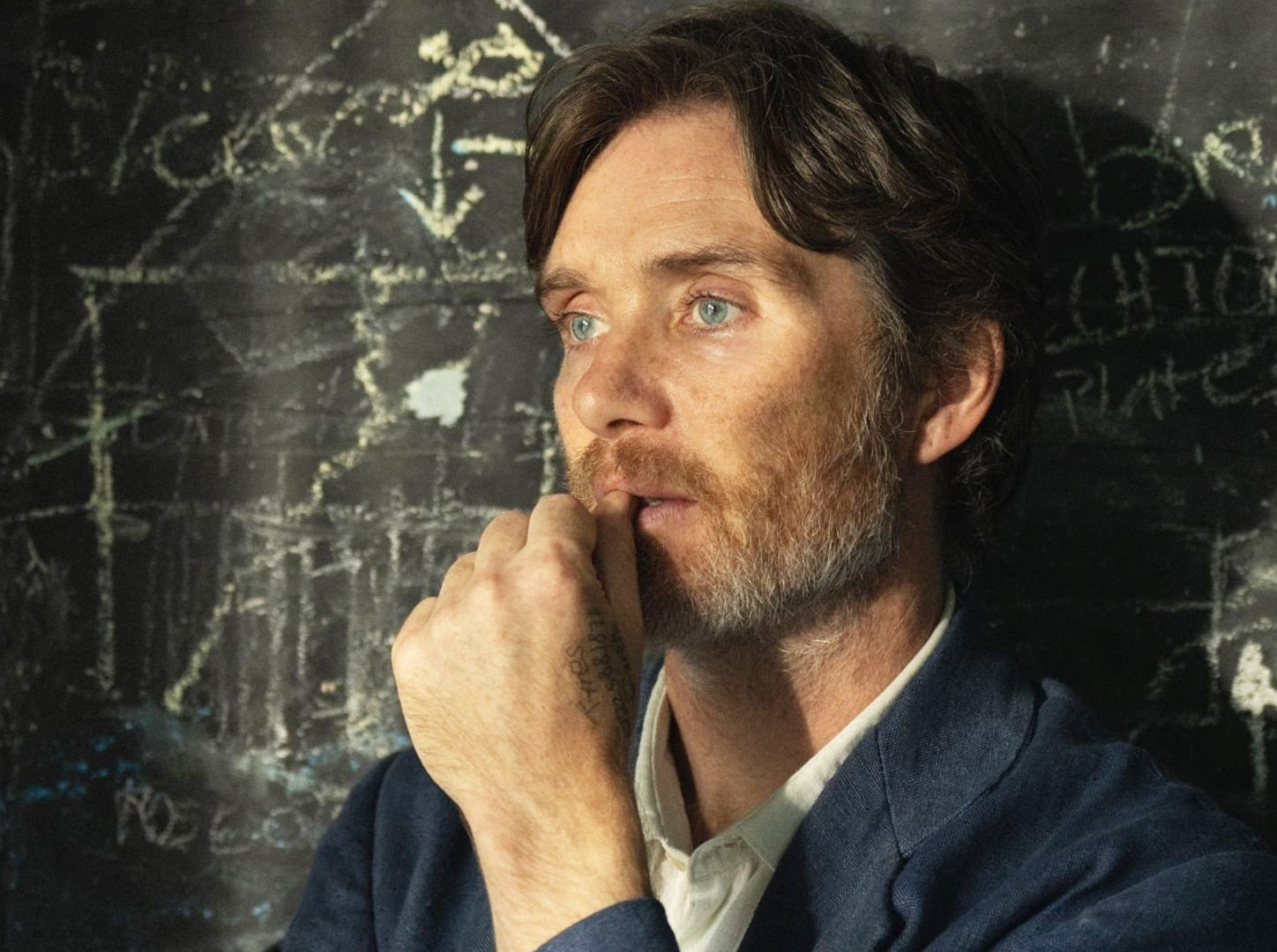

Cillian Murphy burns slow and bright in Steve, a bruising but cathartic portrait of care, chaos, and collapse inside an English reform school—now streaming on Netflix.

The “school of hard knocks” drama must deliver students in need of help; a more interesting question is what to do with the teachers. In Dangerous Minds, Michelle Pfeiffer donned a leather jacket and feigned badassery, though her moral authority was never in question: she was wise, compassionate, and insulted by a wholesome Hollywood glow. In Half Nelson, that glow was corroded by the scent of freebased cocaine—a film calibrated to reject the inspirational-teacher archetype, with Ryan Gosling playing a coke-addicted history teacher.

The moving and moody Steve—a “day in the life of” drama set in an English reform school in the 1990s—occupies something of a middle ground, acknowledging that the people we turn to can be just as messed up as anybody else, without making their pain the point. There are kids in need: rough-as-guts delinquents on the fringes of society—perhaps fated to languish in prison cells, but maybe capable of turning their lives around.

And there are adults in need: to wit, the titular headteacher (Cillian Murphy). He’s clearly stressed and struggling, prone to self-medicating and occasional outbursts—both completely understandable given his highly demanding and largely thankless job. The students—which include the smart but unstable Shy (Jay Lycurgo)—are lucky to have him; lucky to have anyone on their side.

Your shrink might be insane, your doctor ill-informed, your scientist an idiot; these are the terribly adult realisations of a complicated world. One of the curious questions in Steve, which I tossed and turned in my mind afterwards, is whether the protagonist’s devotion to his students has, perhaps by necessity, resulted in him pushing his own pain further down. Cillian’s Murphy’s beautifully balanced performance somehow makes that pain feel both distant and close to the surface.

You never doubt Steve’s compassion, or his ability to profoundly help his students, even if it seems like he’s banging his head against a wall. What you do doubt are the social support structures needed to really give the young men a second chance—particularly when Steve is informed, without prior notice or consultation, that the school property has been sold and the institution will be closed before the end of the year.

On this same horrible day—in addition to the students’ usual violent and abusive behaviour—there is a visit from a douchey politician (Roger Allam) and a documentary crew. The latter enables narratively justified exposition and contextual information—the TV presenter, for instance, reflecting on the school during a piece to camera (“some call it a last chance, some call it a very expensive dumping ground for society’s waste product…”).

Directed by Tim Mielants and adapted by Max Porter from his novel, Shy, the film doesn’t have a lot of story, though there’s quite a bit of plot—the difference between a comprehensive narrative and the sequencing and arranging of events. There’s always something for Steve to do—people to talk to, temperatures to cool, disasters to mitigate—but the overlapping story of the school itself is basic. It’s closing down, and this ain’t the kind of movie in which the students participate in a fundraiser, or win a tournament, saving the proverbial farm. The tone is hardly happy-go-lucky, but there are cathartic elements and shades of light and dark, particularly in the final act; you won’t leave feeling smashed by a brick of social realism.

Like the previous collaboration between Mielants and Murphy—the powerful Christmas drama and morality tale Small Things Like These—the film visually impresses with a rough-hewn, grainy look. In Steve, cinematographer Robrecht Heyvaert deploys intimate handheld camerawork that gives the impression of responding to and boosting the performances, closely tuned to the drama and the spaces around it. Almost all this space takes place on school grounds, evoking a very vivid impression of it.

Most vivid of all are the characters, particularly Steve. He’s a fine addition to the cinematic classroom: not quite the “cool” teacher, nor the “real” student in the school of life. In this film, the emotional needs of its characters overtake the usual clichés: no one’s being saved, no one’s delivering a pat life-changing speech. And yet it feels rich, humane, and rewarding.