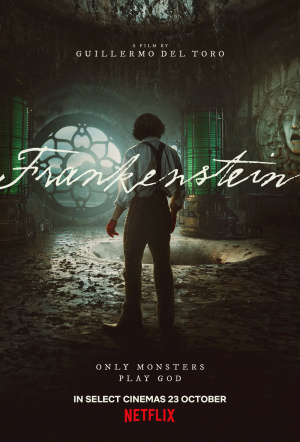

The monstrous, magical world of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein

This movie could be a savage, gory (and it is very gory) fantasy world, but it is so much more emotional, intelligent and beautiful.

The mystery and paradox of the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has attracted writers, painters, directors, and academics for well over a century. The concept of a man-made living creature – whether robotically, in a science lab, through medical experimentation, or via artificial intelligence – raises the same, timeless questions. Is it ethical and who gets to decide that? And, if that creature wreaks havoc, perhaps even kills people, can it be held responsible or is it the creator who must bear the blame?

Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein

Whether it is the artificial intelligence-created boyfriends and girlfriends proliferating in modern relationships (the Frankensteins of your algorithm), or the political leaders we turned into monsters by voting them into power (ahem), it’s no wonder directors have embraced the parable anew. Indeed, Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Bride!, starring Christian Bale and Jessie Buckley, is another Frankenstein re-telling, due out in March next year.

But it is Mexican director Guillermo del Toro’s visual feast of a film that should not be overlooked. Sure, it’s Netflix-backed but no corners have been cut in the production of this glamorous, gothic production. For fans of del Toro’s textured, layered, beautiful cinematic worlds, there is a familiarity to the surreal, wondrous landscapes. If this is your first del Toro, it’s utterly magical and likely to be the gateway drug to Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), Pinocchio (2022), The Shape of Water (2017), and one of my favourites, Hellboy.

Hellboy

The Shape of Water

Jacob Elordi is magnificent. Though Oscar Isaac tends towards the overwrought, florid gestures and speeches more suited to a schlock horror movie, Elordi’s “monster” is gentle, childlike, curious and bewildered by the creatures and landscape he’s landed in. It is impossible not to feel more than a wrench of affection and empathy for this human-like person, so thoroughly good despite the brutal behaviour of his father-figure creator, Victor.

Wrapped into this tale are so many questions and possible allegories. Is human nature the result of genetic inheritance, or the circumstances of our childhood? Are we inherently afraid of anyone or anything that doesn’t look or behave exactly as we do? Is religious dogma from many centuries ago still dictating what moral and political principles we uphold?

One of the most poignant lessons that the creature shares in a voice-over in his slightly stilted, naïve tones, is that men will “inevitably” be violent: hunting and killing targets merely for existing, regardless of real or imagined provocation. That is a startling, truly monstrous idea, and one that rings true. So, naturally, humans want to believe we are superior to AI, or animals, and there’s a worth placed on us based on financial worth, academic performance, sporting prowess. And yet, we’re a species that hunt, kill and triumph in minor victories in this cycle of violence.

Victor, as his younger brother William says in his final, dying breath, is “the monster”. The first part of the movie introduces young Victor, deeply attached to his attentive and loving mother, and fearful of his brutal, sneering surgeon father. Victor is repeatedly subjected to lashings for forgetting the form and function of obscure anatomical parts, and Victor inflicts this savage means of passing on knowledge upon his “monster”, lashing him and locking him underground.

The women – and the sole women characters in del Toro’s movie – are Victor’s mother, and the object of his romantic affections, his brother’s fiancée Elizabeth. Both women are portrayed by Mia Goth. Given little to say bar some pretty hammy speeches, Goth manages to imbue her Elizabeth with enormous sympathy, generosity, and – at the risk of sounding too corny – love. She is unafraid of Elordi’s hulking, muscular, scarred and disfigured creature. From the moment of meeting him, she is bewitched by his naivete and fear. Perhaps it’s too simplistic to theorise this, but women – especially in the archaic old Britain of yore – were expected to be silent, subservient, mimicking the mannerisms of their mothers. Women, like Frankenstein’s creature, were dependent on men of means, and thoroughly without agency. Elizabeth herself is used as a trading card. When Victor refuses to give eternal life to his benefactor, Elizabeth’s uncle, the man insists he will give Victor all he desires, including Elizabeth in marriage.

This movie could be a savage, gory (and it is very gory) fantasy world of monsters, wild men, and gold-hearted women, but it is so much more emotional, intelligent and beautiful. That is largely down to Elordi’s sympathetic portrayal of a character who has become iconic in the literary and film worlds. Who hasn’t felt betrayed by their parents, or the leaders we put in power to ostensibly care for us? Who hasn’t felt targeted for some aspect of who we are that is both undeniable and natural? Who hasn’t watched violence occurring – in person or on social media – and felt powerless at history repeating? If nothing else draws us as viewers to this creature, then these eminently human things must.

The question in Mary Shelley’s original novel is the same one del Toro boils this movie down to: however we’re made, whether artificial or biological, what differentiates a monster from a valuable, living, breathing person?