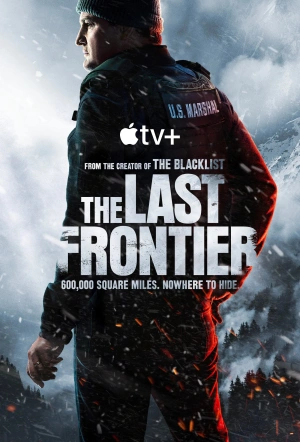

Straddling bad and camp, is thriller The Last Frontier silly enough to be fun?

A prison plane crashes in the Alaskan wilderness in Apple TV+’s new thriller series, setting in motion a chain of events that has us scratching our heads.

The Last Frontier is a real conundrum. It transformed me into some kind of textual detective—feverishly pacing, pinning plot points and lines of dialogue up on the wall, pins and yarn in hand. Always, I’d come back to the same damn question: is this show bad? Or knowingly bad, and therefore a little camp?

Allow me to lay down the evidence. The Last Frontier—out now on the home of prestige television, Apple TV+—stars Jason Clarke as Supervisory Deputy US Marshal Frank Remnick, a brick-jawed, dependable pillar of American masculinity. He’s about to retire so he can buy a cabin in the woods with his wife Sarah (Simone Kessell) and kid Luke (Tait Blum) and open a bed and breakfast. They’re all in Alaska, in a community remote enough that Frank stumbles across a moose on his morning run. Everyone is harmonious and happy.

Related reading:

* Monster: The Ed Gein Story tries to make him the victim of our voyeurism

* House of Guinness blends sex and desire with Ireland’s most famous export

* Gen V hasn’t lost its teeth but, like The Boys, is feeling less “anti-comic book”

Then, a prison transport plane (yes, Con Air) crashes in the snow. There’s a highly dangerous man on board, codenamed Havlock and introduced to us with a hood over his head (yes, The Dark Knight Rises‘ Bane), and in possession of immaculate hand-to-hand combat skills. Some of the prisoners died on impact, some are now gallivanting around the wilderness.

And it’s Frank’s job to not only round them up, but deal with the arrival of CIA agent Sidney Scofield (Haley Bennett). She’s an alcoholic with a dead, agency legend dad and a special connection to Havlock (have a wild guess what it is). Havlock’s identity is initially kept a secret from the audience, but he’s played by that guy you definitely know from that one film, and he keeps cropping up in places in disguise to tell our characters about how super smart and cool Havlock is.

Soon enough, Sarah gets kidnapped. Luke disappears. Alfre Woodard and John Slattery play authority figures. One of Frank’s colleagues congratulates him on achieving “what every marshal dreams of—surviving” and then immediately gets killed off. Endless spy jargon—“Atwater protocol”, “Archive 6”, etc—is spewed out of characters’s mouths as they engage in brisk, Sorkin walk-and-talks and terse boardroom meetings.

Somewhere, at the centre of Jon Bokenkamp and Richard D’Ovidio’s show, lies the conflict between broken systems and the communities that withstand them. It’s curious that so many of the escapee prisoners have their own manifestos, a rage against mass surveillance or the failures of healthcare.

“We choose to be here,” Frank says. “It’s what tradition looks like… a choice to be accountable.” The Last Frontier at least ensures Native communities are included in that sentiment, though the way Dallas Goldtooth’s Hutch seems to exist largely in support of our heroes and to impart Indigenous wisdom seems a little tokenistic. Either way, those ideas never really reach a destination, especially as Scofield’s own potted history moves in to eat up all of the attention.

And yet—and yet—the series has the most disconcertingly jaunty opening credits, so that the line “my wife’s life depends on it” cuts directly into skedaddling guitar riffs. And, in almost every episode, there will be a single, propulsive, utterly nonsensical action sequence (Extraction’s Sam Hargrave directs a couple of episodes, and appears in a small role), in which prisoners pinwheel their arms and snarl like zombies, a transport vehicle hangs off the back of a helicopter, or Scofield fights her way through a cabin to the sound of Free Bird.

Cars flip. People fall from heights in that corny, pure CGI way. Does that make The Last Frontier silly enough to be fun? Do the ends justify the means? I truly don’t know.